Digital music and selfies: the legacy of Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier

Manuel Spagnolo

Posted on May 5, 2019

Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier is one of the most known mathematical personalities in history and with a good reason: he’s the father of Harmonic Analysis also known as Fourier Analysis. We are about to learn how this is the reason why we can stream music, share images and even have echo-cancelling headphones or perform sound searches.

Originally posted on Full-Stack with Benefits

Photo by Tim Marshall on Unsplash

A bit of history

As a lot of the scientists of his time, he was a full-stack mathematician: his work has spanned Mathematics, Thermodynamics, Chemistry down to Engineering.

He also contributed to the “Description de l’Égypte”, although I am not sure whether Egyptology falls under the mathematical spectrum of full-stackness…

Along with his scientific career he was also a key member of the French Revolution and a loyal man in the service of Napoleon Bonaparte. Precisely at that time, he was called to solve a very practical problem which was affecting armed forces: how do we cool down guns and keep them usable during a very busy battle?

This lead to Fourier’s Theorem (and its byproducts Fourier Transforms) which are exactly the way computers and hi-tech gizmos deal with music and images.

Yeah, warm guns really relate to bathroom selfies…

Fourier basic idea was simple yet brilliant: heat waves — no matter how complicated they are — can be decomposed as sum of elementary waves.

Albeit this was a clever intuition, Fourier did not prove it in modern rigorous terms1. However, his was not a lucky shot.

The decomposition of periodic functions in smaller elementary functions dates back to 3rd century BC when Ptolemaic astronomy tried to explain the motion of the planets. Also, the idea that studying heat waves could be related to periodic functions was not entirely new: Euler, d’Alambert and Daniel Bernoulli put together some solutions for the heat problem which happened to work only when the heat source behaved like an elementary wave.

Anyway, in one hundred years time the whole matter will be completely settled by Dirichlet and Riemann who will put the pieces together and give Harmonic Analysis a proper mathematical foundation.

As a matter of fact, such mathematical foundation is the very reason why we can use Fourier’s results outside of that domain: heat waves are just… waves, so as long as a given signal can be turned into waves, we can apply Fourier’s results to study them.

Now your ridiculously boring hours in physics classes make sense: both light which ultimately forms images and sounds are waves. Hence, they can be analyzed using Fourier’s Theorem.

Fourier Analysis for the rest of us

First things first: from a mathematical point of view, signals can be thought as functions. So in the following lines — as a common practice in Harmonic Analysis in general — we’ll be referring interchangeably to “functions” and “signals”.

The whole idea behind Fourier’s work was to rewrite “any given function”2 as sum of elementary periodic chunks. As you remember from high school, the most elementary periodic things you can think of are sine or cosine and these small chunks are usually named oscillations.

Therefore, in Fourier terms all signals can be written like

where a coefficients can be thought as the average of the function we want to represent on a given interval. Such interval is called period and happens to be the period of the oscillations.

The key idea behind decomposition in oscillations is the following: the more you want to be precise the further you have to go in summing oscillations. Thence, the way to increase precision is to sum infinite chunks. Infinite sums in mathematics are called series and this is the shape of the Fourier Series for a given function:

One detail we omitted was that the above works for periodic signals. What happens when the signal is not already periodic? Luckily, the above still holds true to a certain extent and the generalization falls under the name of Fourier Transform. We’re not going to dig deeper on this.

A quick example

A simple way to picture this is thinking about what happens with music. Let’s say, for the sake of the argument, that each note emitted by a piano can be represented as a sinusoidal wave3. When you play a chord — namely more notes and once — you are producing a wave which is formed by summing all those waves.

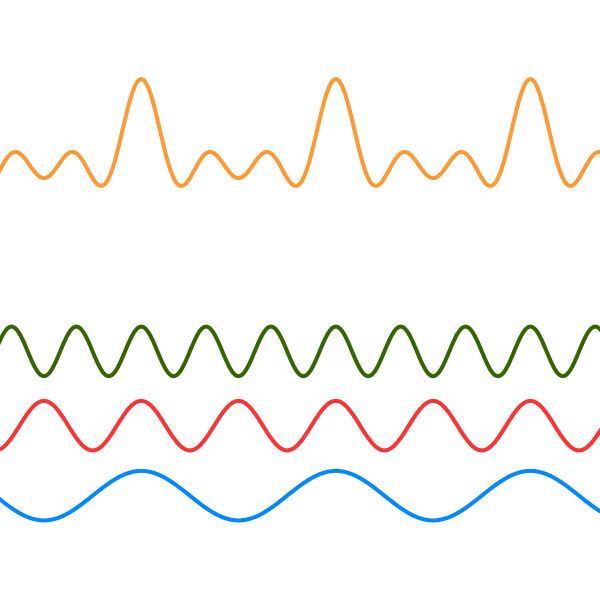

Top wave (the chord wave) is the sum of bottom notes waves (the notes waves)

Top wave (the chord wave) is the sum of bottom notes waves (the notes waves)

What you get then is a complex signal which is ultimately given by the sum of elementary signals. The peak of the chord wave (the yellow one) happens when all the three node waves are at their peak, whereas none of the bottoms of the chord wave are as low in comparison: this is due to the fact that there is no moment when the three of them are at their bottom concurrently.

Applications in everyday life

Now, what you might be wondering how summing infinite things can lead to a non-infinite, hence meaningful, result. This problem is rather general in Mathematics, it is called convergence and unfortunately cannot be treated within this article because of its complexity.

However, one very evident thing can be observed here: to make this sum to not go to infinity (i.e. diverge), we need chunks which get smaller and smaller. This in turn implies that some items in the sum are holding the greatest part of the information needed to represent the original signal.

This last observation is what makes Spotify, Shazam, Instagram and even your iPhone’s guitar tuner app or noise canceling headphones possible.

In fact, when you are playing your music via Spotify you are not listening to the song exactly as it has been recorded. In order to provide a continuous data flow and keep the track going without needing to download it in advance, Spotify applies a compression algorithm which is meant to reduce file size enough to be streamed in real time.

What this algorithm does is:

spot oscillations related to frequencies at end of or beyond the human audible spectrum and shave them off;

remove the oscillations which do not hold a lot of information, namely the “rest” of the series.

The same principle applies to Shazam, SoundHound or even Siri and Google Assistant: when you provide a sound input, these software need to clean it, for example, removing frequencies which go beyond the average human voice spectrum and taking away minor oscillations. The actual search then happens comparing the coefficients of same oscillations between your input and a dataset.

Noise cancelling headphones work the same way: they have a microphone which records the ambient sound and calculates oscillations. Then they flip the oscillations so that the sum with the sound around you yields a silent wave. Eventually they inject this flipped wave in your mix so that frequencies outside of your music are not audible.

For images the things get a bit trickier because in that case we have to speak about two-dimensional Fourier Transform as the image signal spans across two dimensions. The underlying idea though stays the same: when we share a picture on Instagram, an algorithm chunks the image and applies the same kind of approximation we have seen above on every single pixel. This time around the computation happens on things like color spectrum and brightness and elements which live at the border of our perception are tossed away.

Conclusion

Every time you will see your younger sister’s bathroom selfies on Instagram or you listen to a Ed Sheeran song on Spotify, now you know who to blame. Do you think that in hindsight Fourier would have spread this knowledge?

Until next time!

-

It was not his fault though: at that time we did not have a clear definition of integral nor of function. It was in fact impossible to prove Fourier’s Theorem from a modern perspective. ↩

-

Mathematically speaking this is sooo wrong. Unfortunately we live in a faulty world, where most of the time engineers go with this kind of assumptions and and we settle for approximated solutions. ↩

-

Actually each and every note is already a sum of sinusoidal waves. The set of waves which contributes to the sound of a note as we perceive it is called Harmonic Series and the single waves are called Harmonics. ↩

Posted on May 5, 2019

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.