Designing A Voting System For 1 Billion on the Blockchain (Part 2) - How To Keep A Secret

Pranith Hengavalli

Posted on October 19, 2018

This post is part two of a series about large scale voting on the Blockchain. In my previous post, we discussed what a large network would look like, and how consensus could be achieved with so many votes placed at the same time. This post focuses on how it works from the perspective of a single voter.

One of the key features of Blockchain as we know it is the 'decentralised ledger', a public store of every single block that is synchronised across all participants. This system was traditionally designed to allow for data to be open and publicly verifiable, but this could have negative impacts on elections. For instance, being able to tally the votes privately before the election is finished could lead to confirmation bias in minds of the voters.

Some of the key considerations from the voters' perspective are:

- Choice of candidate must remain secret

- Vote counting should be public and accountable

- Tamper proof by a third party

The ancient system of dropping papers in a ballot box is really great at this. All the votes are mixed up in the box, no secret votes were present before they started, and at the end, all they have to do is count all the papers in public. One could add that thanks to VVPAT (Indian voting machines print each vote on a slip and drop them into a sealed box), one simply has to follow their vote until the counting rooms to be sure that their vote was indeed placed. Too bad they don't actually count the printed papers, and the error begins with the manual uploading of votes from each voting machine, 3840 votes at a time. Entire batches could be misrepresented or misplaced.

A VVPAT machine printing out a ballot

The blockchain-based voting procedure could look a little like this:

A. EVM Initialisation

In India, voters are each registered to areas known as constituencies, where they are allowed to cast a vote. This makes it much easier to verify that an individual exists on paper, something that becomes increasingly difficult in remote areas without active network connectivity.

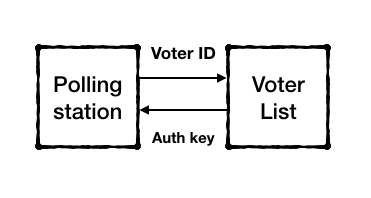

In the case of a Blockchain EVM, it would be initialised before the starting of each election. It receives a list of eligible voters for that region, as well as a unique key that is used to sign votes while casting them. This can be done at the last possible minute before elections begin, while network is still available.

B. Voter Authentication

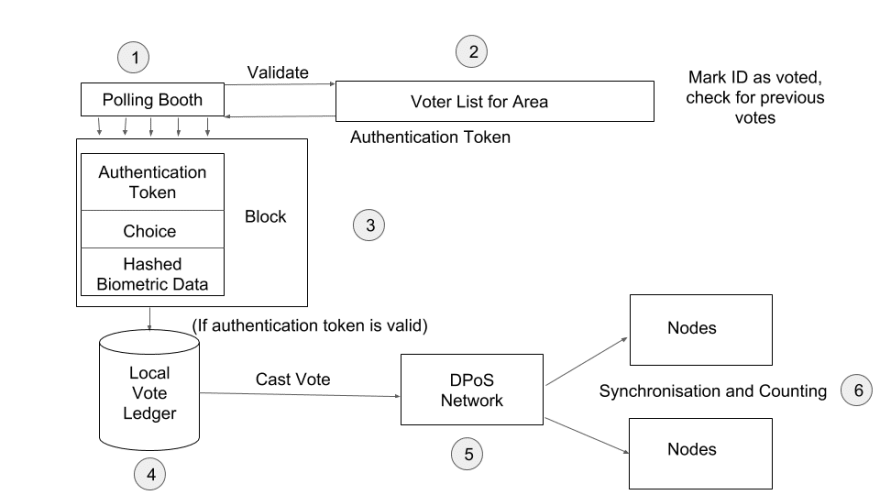

When a voter identifies themselves with a voter ID, it is verified against the local voter list. If the ID is present, a key-pair is generated for the voter, with the 'opening' private key stored against their name and the public key used to encrypt or 'seal' their vote choice. This sealed choice is then stored on the local ledger, ready to be sent to the central voting nodes.

C. Vote Accumulation

One of the biggest problems faced in India is the communication barrier experienced by people living in remote regions. Though network coverage has greatly improved, it still isn't reliable enough in remote areas to handle too much traffic. This is why the current EVMs still need to be physically shifted to the Election Commission for counting.

With better connectivity, I suggest a more hybrid approach to this, where votes are stored in chunks locally until a stable connection is established. Chunking votes also makes it harder to place individual fraudulent votes from a rogue machine.

D. Vote Casting

When enough votes accumulate and a stable internet connection is established, a chunk of votes is pushed to the delegated voting servers. These chunks are signed by the EVM with the key that was created during initialisation. The chunks can be sent to any of the available delegates, which can then add them to the longest available vote chain.

E. Vote Counting

When the voting period is declared closed, a signal is sent from the voting servers to EVMs, requesting the 'opening' private keys for all the 'sealed' votes. Since votes from each constituency are grouped in chunks, it is easier to find chunks from a particular EVM and unseal all corresponding votes with the matching private keys. Any votes that were placed by unauthorised EVMs would remain unopened as they would be unable to send opening values to the voting servers.

One of the primary advantages of this method is that there is much more accountability for each vote, as the vote cannot be counted until the second round of confirmation when the votes are unsealed. Since the Voter ID is not sent back from the EVMs, it becomes impossible to associate the choice made and the voter ID from the perspective of the counting servers.

Finally, the unsealed votes are counted and we can conclude how many votes were placed for each candidate.

Of course, practical implementation of such a system could take a long time. We would need to design robust hardware, conduct practical tests, and address the fact that the new system would create a whole new set of vulnerabilities. The cost of manufacturing alone would encourage policy makers to prefer a solution which can be built on top of the existing voting infrastructure. However, I hope we can spark a conversation about how blockchain design concepts present us with a brand new way of building systems that are performant and secure at massive scale.

Posted on October 19, 2018

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.

Related

October 19, 2018