Rust and Node.js: A match made in heaven

Brian Neville-O'Neill

Posted on May 18, 2020

Written by Anshul Goyal✏️

Node.js is a very popular JavaScript runtime for writing backend applications. Its flexibility and nonblocking nature have made it the premier choice for API consumption.

Since it is a scripting language, JavaScript can be pretty slow. But thanks to V8 optimization, it is fast enough for practical applications. That said, Node.js is not good for heavy lifting; since it’s single-threaded, it is dangerous to block the main thread for doing long calculations. That’s where worker threads come in. Node.js has support for worker threads, so it can be used to perform long calculations.

As great as worker threads are, JavaScript is still slow. Moreover, worker thread are not available in all supported LTS versions of Node. Fortunately, we can use Rust to build a native add-on for Node.js. FFI is another alternative, but it’s slower than the add-on approach. Rust is blazing fast and has fearless concurrency. Since Rust has a very small runtime (or “not runtime”), our binary size should also be pretty small.

What is Rust?

Rust is a systems programming language by Mozilla. It can call the C library by default and includes first-class support for exporting functions to C.

Rust provides you with low-level control and high-level ergonomics. It gives you control of memory management without the hassle associated with these controls. It also delivers zero-cost abstraction, so you pay for only what you use.

Rust can be called in a Node.js context via various methods. I’ve listed some of the most widely used below.

- You can use FFI from Node.js and Rust, but this is very slow

- You can use WebAssembly to create a

node_module, but all Node.js functionality is not available - You can use native addons

What is a native addon?

Node.js addons are shared objects written in C++ that are dynamically linked. You can load them into Node.js using the require() function and use them as if they were ordinary Node.js modules. They primarily provide an interface between JavaScript running in Node.js and C/C++ libraries.

A native addon provides a simple interface to work with another binary by loading it in V8 runtime. It is very fast and safe for making calls across the languages. Currently, Node.js supports two types of addon methods: C++ addons and N-API C++/C addons.

C++ addons

A C++ addon is an object that can be mounted by Node.js and used in the runtime. Since C++ is a compiled language, these addons are very fast. C++ has a wide array of production-ready libraries that can be used to expand the Node.js ecosystem. Many popular libraries use native addons to improve performance and code quality.

N-API C++/C addons

The main problem with C++ addons is that you need to recompile them with every change to underlying JavaScript runtime. It causes a problem with maintaining the addon. N-API tries to eliminate this by introducing a standard application binary interface (ABI). The C header file remains backward compatible. That means you can use the addon compiled for a particular version of Node.js with any version greater than the version for which it was compiled. You would use this method to implement your addon.

Where does Rust come in?

Rust can mimic the behavior of a C library. In other words, it exports the function in a format C can understand and use. Rust calls the C function to access and use APIs provided by the Node.js. These APIs provide methods for creating JavaScript strings, arrays, numbers, error, objects, functions, and more. But we need to tell Rust what these external functions, structs, pointers, etc. look like.

#[repr(C)]

struct MyRustStruct {

a: i32,

}

extern "C" fn rust_world_callback(target: *mut RustObject, a: i32) {

println!("Function is called from C world", a);

unsafe {

// Do something on rust struct

(*target).a = a;

}

}

extern {

fn register_callback(target: *mut MyRustStruct,

cb: extern fn(*mut MyRustStruct, i32)) -> i32;

fn trigger_callback();

}

Rust lays down the structs in memory differently, so we need to tell it to use the style C uses. It would be a pain to create these functions by hand, so we’ll use a crate called nodejs-sys, which uses bindgen to create a nice definition for N-API.

bindgen automatically generates Rust FFI bindings to C and C++ libraries.

Note: There will a lot of unsafe code ahead, mostly external function calls.

Setting up your project

For this tutorial, you must have Node.js and Rust installed on your system, with Cargo and npm. I would suggest using Rustup to install Rust and nvm for Node.js.

Create a directory named rust-addon and initialize a new npm project by running npm init. Next, init a cargo project called cargo init --lib. Your project directory should look like this:

├── Cargo.toml

├── package.json

└── src

└── lib.rs

Configuring Rust to compile to the addon

We need Rust to compile to a dynamic C library or object. Configure cargo to compile to the .so file on Linux, .dylib on OS X, and .dll on Windows. Rust can produce many different types of libraries using Rustc flags or Cargo.

[package]

name = "rust-addon"

version = "0.1.0"

authors = ["Anshul Goyal <anshulgoel151999@gmail.com>"]

edition = "2018"

# See more keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

[lib]

crate-type=["cdylib"]

[dependencies]

nodejs-sys = "0.2.0"

The lib key provides options to configure Rustc. The name key gives the library name to the shared object in the form of lib{name}, while type provides the type of library it should be compiled to — e.g., cdylib, rlib, etc. cdylib creates a dynamically linked C library. This shared object behaves like a C library.

Getting started with N-API

Let’s create our N-API library. We need to add a dependency. nodejs-sys provides the binding required for napi-header files. napi_register_module_v1 is the entry point for the addon. The N-API documentation recommends N-API_MODULE_INIT macro for module registration, which compiles to the napi_register_module_v1 function.

Node.js calls this function and provides it with an opaque pointer called napi_env, which refers to the configuration of the module in JavaScript runtime, and napi_value. The latter is another opaque pointer that represents a JavaScript value, which, in reality is an object known as an export. These exports are the same as those the require function provides to the Node.js modules in JavaScript.

use nodejs_sys::{napi_create_string_utf8, napi_env, napi_set_named_property, napi_value};

use std::ffi::CString;

#[no_mangle]

pub unsafe extern "C" fn napi_register_module_v1(

env: napi_env,

exports: napi_value,

) -> nodejs_sys::napi_value {

// creating a C string

let key = CString::new("hello").expect("CString::new failed");

// creating a memory location where the pointer to napi_value will be saved

let mut local: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

// creating a C string

let value = CString::new("world!").expect("CString::new failed");

// creating napi_value for the string

napi_create_string_utf8(env, value.as_ptr(), 6, &mut local);

// setting the string on the exports object

napi_set_named_property(env, exports, key.as_ptr(), local);

// returning the object

exports

}

Rust represents owned strings with the String type and borrowed slices of strings with the str primitive. Both are always in UTF-8 encoding and may contain null bytes in the middle. If you look at the bytes that make up the string, there may be a \0 among them. Both String and str store their length explicitly; there are no null terminators at the end of strings like C strings.

Rust strings are very different from the ones in C, so we need to change our Rust strings to C strings before we can use then with N-API functions. Since exports is an object represented by exports, we can add functions, strings, arrays, or any other JavaScript objects as key-value pairs.

To add a key to a JavaScript object, you can use a method provided by the N-API napi_set_named_property. This function takes the object to which we want to add a property; a pointer to a string that will be used as the key for our property; the pointer to the JavaScript value, which can be a string, array, etc.; and napi_env, which acts an anchor between Rust and Node.js.

You can use N-API functions to create any JavaScript value. For example, we used napi_create_string_utf8 here to create a string. We passed in the environment a pointer to the string, the length of string, and a pointer to an empty memory location where it can write the pointer to the newly created value. All this code is unsafe because it includes many calls to external functions where the compiler cannot provide Rust guarantees. In the end, we returned the module that was provided to us by setting a property on it with the value world!.

It’s important to understand that nodejs-sys just provides the required definitions for the function you’re using, not their implementation. N-API implementation is included with Node.js and you call it from your Rust code.

Using the addon in Node.js

The next step is to add a linking configuration for different operating systems, then you can compile it.

Create a build.rs file to add a few configuration flags for linking the N-API files on different operating systems.

fn main() {

println!("cargo:rustc-cdylib-link-arg=-undefined");

if cfg!(target_os = "macos") {

println!("cargo:rustc-cdylib-link-arg=dynamic_lookup");

}

}

Your directory should look like this:

├── build.rs

├── Cargo.lock

├── Cargo.toml

├── index.node

├── package.json

├── src

└── lib.rs

Now you need to compile your Rust addon. You can do so pretty easily using the simple command cargo build --release. This will take some time on the first run.

After your module is compiled, create a copy of this binary from ./target/release/libnative.so to your root directory and rename it as index.node. The binary created by the cargo may have a different extension or name, depending on your crate setting and operating system.

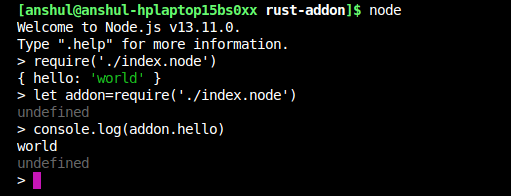

Now you can require the file in Node.js and use it. You can also use it in a script. For example:

let addon=require('./index.node');

console.log(addon.hello);

Next, we’ll move on to creating functions, arrays, and promises and using libuv thread-pool to perform heavy tasks without blocking the main thread.

A deep dive into N-API

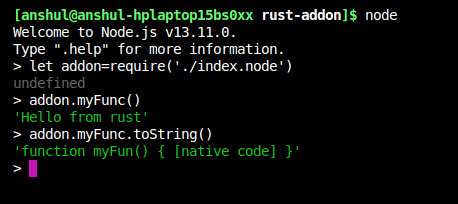

Now you know how to implement common patterns using N-API and Rust. A very common pattern is the export function, which can be called by the user of the library or Node module. Let’s start by creating a function.

You should use napi_create_function to create your functions so that you can use them from Node.js. You can add these functions as a property to exports to use from Node.js.

Creating a function

JavaScript functions are also represented by the napi_value pointer. A N-API function is pretty easy to create and use.

use nodejs_sys::{

napi_callback_info, napi_create_function, napi_create_string_utf8, napi_env,

napi_set_named_property, napi_value,

};

use std::ffi::CString;

pub unsafe extern "C" fn say_hello(env: napi_env, _info: napi_callback_info) -> napi_value {

// creating a javastring string

let mut local: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

let p = CString::new("Hello from rust").expect("CString::new failed");

napi_create_string_utf8(env, p.as_ptr(), 13, &mut local);

// returning the javascript string

local

}

#[no_mangle]

pub unsafe extern "C" fn napi_register_module_v1(

env: napi_env,

exports: napi_value,

) -> nodejs_sys::napi_value {

// creating a C String

let p = CString::new("myFunc").expect("CString::new failed");

// creating a location where pointer to napi_value be written

let mut local: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_function(

env,

// pointer to function name

p.as_ptr(),

// length of function name

5,

// rust function

Some(say_hello),

// context which can be accessed by the rust function

std::ptr::null_mut(),

// output napi_value

&mut local,

);

// set function as property

napi_set_named_property(env, exports, p.as_ptr(), local);

// returning exports

exports

}

In the above example, we created a function in Rust named say_hello, which is executed when the JavaScript calls the function. We created a function using napi_create_function, which takes the following arguments:

- The

napi_envvalue of the environment - A string for the function name which that be given to the JavaScript function

- The length of the function name string

- The function that is executed when the JavaScript calls the newly created function

- Context data that can be passed by the user later and accessed from the Rust function

- An empty memory address where the pointer to the JavaScript function can be saved

- When you create this function, add it as a property to your

exportsobject so that you can use it from JavaScript

The function on the Rust side must have the same signature as shown in the example. We’ll discuss next how to access arguments inside a function using napi_callback_info. We can access this from a function and other arguments as well.

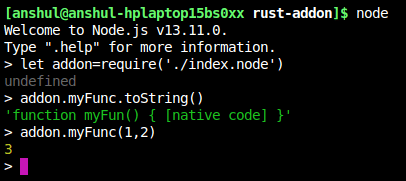

Accessing arguments

Function arguments are very important. N-API provides a method to access these arguments. napi_callback_info provides the pointer with detailed information about the function in the JavaScript side of the code.

use nodejs_sys::{

napi_callback_info, napi_create_double, napi_create_function, napi_env, napi_get_cb_info,

napi_get_value_double, napi_set_named_property, napi_value,

};

use std::ffi::CString;

pub unsafe extern "C" fn add(env: napi_env, info: napi_callback_info) -> napi_value {

// creating a buffer where napi_value of argument be written

let mut buffer: [napi_value; 2] = std::mem::MaybeUninit::zeroed().assume_init();

// max number of arguments

let mut argc = 2 as usize;

// getting arguments and value of this

napi_get_cb_info(

env,

info,

&mut argc,

buffer.as_mut_ptr(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

);

// converting napi to f64

let mut x = 0 as f64;

let mut y = 0 as f64;

napi_get_value_double(env, buffer[0], &mut x);

napi_get_value_double(env, buffer[1], &mut y);

// creating the return value

let mut local: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_double(env, x + y, &mut local);

// returning the result

local

}

#[no_mangle]

pub unsafe extern "C" fn napi_register_module_v1(

env: napi_env,

exports: napi_value,

) -> nodejs_sys::napi_value {

// creating a function name

let p = CString::new("myFunc").expect("CString::new failed");

let mut local: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

// creating the function

napi_create_function(

env,

p.as_ptr(),

5,

Some(add),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut local,

);

// setting function as property

napi_set_named_property(env, exports, p.as_ptr(), local);

// returning exports

exports

}

Use napi_get_cb_info to get the arguments. The following arguments must be provided:

napi_env- The info pointer

- The number of expected arguments

- A buffer where arguments can be written as

napi_value - A memory location to store metadata the user provided when JavaScript function was created

- A memory location where this value pointer can be written

We need to create an array with memory locations where C can write a pointer to arguments and we can pass this pointer buffer to N-API function. We also get this, but we aren’t using it in this example.

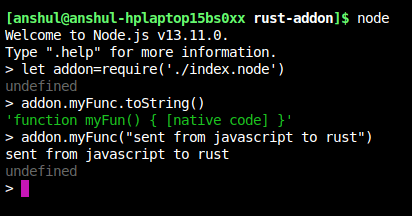

Working with strings arguments

Most of the time, you need to work with strings in JavaScript. Both creating and getting the value of a string are pretty straightforward. Use napi_get_value_string_utf8 and call this function twice: the first time to get length and second time to get the value of the string.

use nodejs_sys::{

napi_callback_info, napi_create_function, napi_env, napi_get_cb_info, napi_get_undefined,

napi_get_value_string_utf8, napi_set_named_property, napi_value,

};

use std::ffi::CString;

pub unsafe extern "C" fn print(env: napi_env, info: napi_callback_info) -> napi_value {

// creating a buffer of arguments

let mut buffer: [napi_value; 1] = std::mem::MaybeUninit::zeroed().assume_init();

let mut argc = 1 as usize;

// getting arguments

napi_get_cb_info(

env,

info,

&mut argc,

buffer.as_mut_ptr(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

);

let mut len = 0;

// getting length by passing null buffer

napi_get_value_string_utf8(env, buffer[0], std::ptr::null_mut(), 0, &mut len);

let size = len as usize;

// creating a buffer where string can be placed

let mut ve: Vec<u8> = Vec::with_capacity(size + 1);

let raw = ve.as_mut_ptr();

// telling rust not manage the vector

std::mem::forget(ve);

let mut cap = 0;

// getting the string value from napi_value

let _s = napi_get_value_string_utf8(env, buffer[0], raw as *mut i8, size + 1, &mut cap);

let s = String::from_raw_parts(raw, cap as usize, size);

// printing the string

println!("{}", s);

// creating an undefined

let mut und: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_get_undefined(env, &mut und);

// returning undefined

und

}

#[no_mangle]

pub unsafe extern "C" fn napi_register_module_v1(

env: napi_env,

exports: napi_value,

) -> nodejs_sys::napi_value {

let p = CString::new("myFunc").expect("CString::new failed");

let mut local: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_function(

env,

p.as_ptr(),

5,

Some(print),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut local,

);

napi_set_named_property(env, exports, p.as_ptr(), local);

exports

}

You’ll need to pass a few arguments to napi_create_string_utf8 to create a string. If a null pointer is passed as a buffer, the length of the string is given. The following arguments are required:

napi_env-

napi_valuepointer to the string injavascript side - The buffer where the string is to be written if null gives the length of the string

- The length of the buffer

- Bytes written to the buffer

Working with promises and libuv thread pool

It’s not a good idea to block the main thread of Node.js for doing calculations. You can use libuv threads to do the heavy lifting.

First, create a promise. The promise will reject or resolve based on the success of your work. For this, you’ll need to create three functions. The first one is called from the JavaScript world and the control would be passed to the second function, which runs on libuv thread and has no access to JavaScript. The third function, which does have access to the JavaScript side, is called after the second finishes. You can use the napi_create_async_work method for the libuv thread.

Creating a promise

To create a promise, simply use napi_create_promise. This will provide a pointer, napi_deferred, which can then resolve or reject a promise using the following functions:

napi_resolve_deferrednapi_reject_deferred

Error handling

You can create and throw an error from the Rust code using napi_create_error and napi_throw_error. Every N-API function returns a napi_status, which should be checked.

Real code

The following example shows how to schedule async work.

use nodejs_sys::{

napi_async_work, napi_callback_info, napi_create_async_work, napi_create_error,

napi_create_function, napi_create_int64, napi_create_promise, napi_create_string_utf8,

napi_deferred, napi_delete_async_work, napi_env, napi_get_cb_info, napi_get_value_int64,

napi_queue_async_work, napi_reject_deferred, napi_resolve_deferred, napi_set_named_property,

napi_status, napi_value,

};

use std::ffi::c_void;

use std::ffi::CString;

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

struct Data {

deferred: napi_deferred,

work: napi_async_work,

val: u64,

result: Option<Result<u64, String>>,

}

pub unsafe extern "C" fn feb(env: napi_env, info: napi_callback_info) -> napi_value {

let mut buffer: Vec<napi_value> = Vec::with_capacity(1);

let p = buffer.as_mut_ptr();

let mut argc = 1 as usize;

std::mem::forget(buffer);

napi_get_cb_info(

env,

info,

&mut argc,

p,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

);

let mut start = 0;

napi_get_value_int64(env, *p, &mut start);

let mut promise: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

let mut deferred: napi_deferred = std::mem::zeroed();

let mut work_name: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

let mut work: napi_async_work = std::mem::zeroed();

let async_name = CString::new("async fibonaci").expect("Error creating string");

napi_create_string_utf8(env, async_name.as_ptr(), 13, &mut work_name);

napi_create_promise(env, &mut deferred, &mut promise);

let v = Data {

deferred,

work,

val: start as u64,

result: None,

};

let data = Box::new(v);

let raw = Box::into_raw(data);

napi_create_async_work(

env,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

work_name,

Some(perform),

Some(complete),

std::mem::transmute(raw),

&mut work,

);

napi_queue_async_work(env, work);

(*raw).work = work;

promise

}

pub unsafe extern "C" fn perform(_env: napi_env, data: *mut c_void) {

let mut t: Box<Data> = Box::from_raw(std::mem::transmute(data));

let mut last = 1;

let mut second_last = 0;

for _ in 2..t.val {

let temp = last;

last = last + second_last;

second_last = temp;

}

t.result = Some(Ok(last));

Box::into_raw(task);

}

pub unsafe extern "C" fn complete(env: napi_env, _status: napi_status, data: *mut c_void) {

let t: Box<Data> = Box::from_raw(std::mem::transmute(data));

let v = match t.result {

Some(d) => match d {

Ok(result) => result,

Err(_) => {

let mut js_error: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_error(

env,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut js_error,

);

napi_reject_deferred(env, t.deferred, js_error);

napi_delete_async_work(env, t.work);

return;

}

},

None => {

let mut js_error: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_error(

env,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut js_error,

);

napi_reject_deferred(env, t.deferred, js_error);

napi_delete_async_work(env, t.work);

return;

}

};

let mut obj: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_int64(env, v as i64, &mut obj);

napi_resolve_deferred(env, t.deferred, obj);

napi_delete_async_work(env, t.work);

}

#[no_mangle]

pub unsafe extern "C" fn napi_register_module_v1(

env: napi_env,

exports: napi_value,

) -> nodejs_sys::napi_value {

let p = CString::new("myFunc").expect("CString::new failed");

let mut local: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_function(

env,

p.as_ptr(),

5,

Some(feb),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut local,

);

napi_set_named_property(env, exports, p.as_ptr(), local);

exports

}

We created a struct to store a pointer to our napi_async_work and napi_deferred as well as our output. Initially, the output is None. Then we created a promise, which provides a deferred that we save in our data. This data is available to us in all of our functions.

Next, we converted our data into raw data and pass it to the napi_create_async_work function with other callbacks. We returned the promise we created, executed perform, and converted our data back to struct.

Once perform is completed on libuv thread, complete is called from the main thread, along with the status of the previous operation and our data. Now we can reject or resolve our work and delete work from the queue.

Let’s walk through the code

Create a function called feb, which will be exported to JavaScript. This function will return a promise and schedule work for the libuv thread pool.

You can achieve this by creating a promise, using napi_create_async_work, and passing two functions to it. One is executed on the libuv thread and the other on the main thread.

Since you can only execute JavaScript from the main thread, you must resolve or reject a promise only from the main thread. The code includes a large number of unsafe functions.

feb function

pub unsafe extern "C" fn feb(env: napi_env, info: napi_callback_info) -> napi_value {

let mut buffer: Vec<napi_value> = Vec::with_capacity(1);

let p = buffer.as_mut_ptr();

let mut argc = 1 as usize;

std::mem::forget(buffer);

// getting arguments for the function

napi_get_cb_info(

env,

info,

&mut argc,

p,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

);

let mut start = 0;

// converting the napi_value to u64 number

napi_get_value_int64(env, *p, &mut start);

// promise which would be returned

let mut promise: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

// a pointer to promise to resolve is or reject it

let mut deferred: napi_deferred = std::mem::zeroed();

// a pointer to our async work name used for debugging

let mut work_name: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

// pointer to async work

let mut work: napi_async_work = std::mem::zeroed();

let async_name = CString::new("async fibonaci").expect("Error creating string");

// creating a string for name

napi_create_string_utf8(env, async_name.as_ptr(), 13, &mut work_name);

// creating a promise

napi_create_promise(env, &mut deferred, &mut promise);

let v = Data {

deferred,

work,

val: start as u64,

result: None,

};

// creating a context which can be saved to share state between our functions

let data = Box::new(v);

// converting it to raw pointer

let raw = Box::into_raw(data);

// creating the work

napi_create_async_work(

env,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

work_name,

Some(perform),

Some(complete),

std::mem::transmute(raw),

&mut work,

);

// queuing to execute the work

napi_queue_async_work(env, work);

// setting pointer to work that can be used later

(*raw).work = work;

// retuning the pormise

promise

}

perform function

pub unsafe extern "C" fn perform(_env: napi_env, data: *mut c_void) {

// getting the shared data and converting the in box

let mut t: Box<Data> = Box::from_raw(std::mem::transmute(data));

let mut last = 1;

let mut second_last = 0;

for _ in 2..t.val {

let temp = last;

last = last + second_last;

second_last = temp;

}

// setting the result on shared context

t.result = Some(Ok(last));

// telling the rust to not to drop the context data

Box::into_raw(t);

}

complete function

pub unsafe extern "C" fn complete(env: napi_env, _status: napi_status, data: *mut c_void) {

// getting the shared context

let t: Box<Data> = Box::from_raw(std::mem::transmute(data));

let v = match task.result {

Some(d) => match d {

Ok(result) => result,

Err(_) => {

// if there is error just throw an error

// creating error

let mut js_error: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_error(

env,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut js_error,

);

// rejecting the promise with error

napi_reject_deferred(env, task.deferred, js_error);

// deleting the task from the queue

napi_delete_async_work(env, task.work);

return;

}

},

None => {

// if no result is found reject with error

// creating an error

let mut js_error: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_error(

env,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut js_error,

);

// rejecting promise with error

napi_reject_deferred(env, task.deferred, js_error);

// deleting the task from queue

napi_delete_async_work(env, task.work);

return;

}

};

// creating the number

let mut obj: napi_value = std::mem::zeroed();

napi_create_int64(env, v as i64, &mut obj);

// resolving the promise with result

napi_resolve_deferred(env, t.deferred, obj);

// deleting the work

napi_delete_async_work(env, t.work);

}

Conclusion

When it comes to what you can do with N-API, this is just the tip of the iceberg. We went over a few patterns and covered the basics, such as how to export functions, create oft-used JavaScript types such as strings, numbers, arrays, objects, etc., get the context of a function (i.e., get the arguments and this in a function), etc.

We also examined an in-depth example of how to use libuv threads and create an async_work to perform heavy calculations in the background. Finally, we created and used JavaScript’s promises and learned how to do error handling in N-APIs.

There are many libraries available if you don’t want to write all the code by hand. These provide nice abstractions, but the downside is that they don’t support all features.

200's only ✅: Monitor failed and show GraphQL requests in production

While GraphQL has some features for debugging requests and responses, making sure GraphQL reliably serves resources to your production app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring network requests to the backend or third party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket is like a DVR for web apps, recording literally everything that happens on your site. Instead of guessing why problems happen, you can aggregate and report on problematic GraphQL requests to quickly understand the root cause. In addition, you can track Apollo client state and inspect GraphQL queries' key-value pairs.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

The post Rust and Node.js: A match made in heaven appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

Posted on May 18, 2020

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.