Event Sourcing and CQRS

Sebastian Kurfürst

Posted on January 1, 2019

I've had the pleasure to join an EventSourcing and CQRS workshop with Mathias Verraes in Frankfurt, to figure out the next steps on how to apply Event Sourcing and CQRS to the Neos Content Repository.

This blog post is about my learnings in general, and not about our specific implementation plans in Neos.

Setting the stage: How state is handled and modified

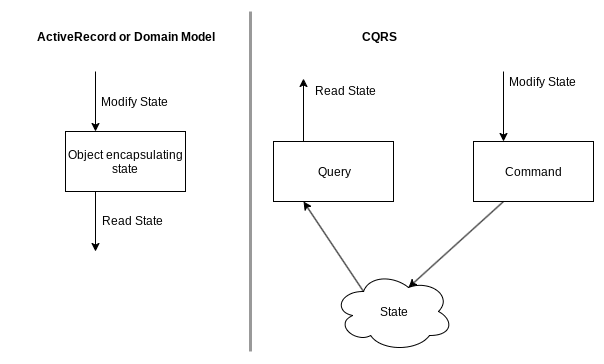

Normally in web applications, people use relational databases to store their application state. Many frameworks apply patterns such as Active Record or Domain Model to make state accessible and to modify it. No matter what pattern is used, usually an object is responsible for both reading from the state as well as updating it. This is different when using CQRS.

CQRS stands for Command Query Responsibility Seggregation; basically meaning that you'll use one object to read from the state (the Query), and a different object to modify the state (the Command).

This allows you to separate the read from the write side; allowing to use different representations for state modification and for reading – and it allows multiple commands and multiple read models to be used (more on that later)!

Normally, you store state in your database. You have tables which contain e.g. the current user name, or the contents displayed currently on your website, or your currently available products. When this state is modified, this happens rather implicitely (e.g. through some method calls resulting in database queries). We'll now think of this state modification as an event.

The core idea behind Event Sourcing is different from the conventional approach: We won't store the current state, but rather all the events that led to it. These events will be stored in an event store, which is conceptually just a long, ordered, append-only list of all events which have ever happened in the system.

This way, we can build up the current state by taking a "blank" state, then applying all events which have ever happened, and then we have the current state. Of course this would be horribly inefficient (more on this later, we're currently on the conceptual level). More than that, we're able to travel forth and back in time: We can also compute all previous states as they existed in the system.

What if we don't store the current state, but rather all events that led to it?

Having access to all previous states which happened in the system is an extremely powerful paradigm: You can, for example, see, how often your data was modified. By whom. What the old value was. So you have an audit log.

Additionally (and that's for me the core benefit), you are able to take all old events in your system and use them to build up additional state for answering different questions than originally anticipated. We'll cover this in a bit.

It turns out that event sourcing and CQRS work together beautifully:

On the write side, you "basically" will just create events which you store in the event store.

On the read side, you consume the events and build up the state you need for your application. This is called a projection.

Commands, Events, and Projections

Let's ensure we are on the same page regarding some core vocabulary:

A command is a state-mutation-intent. It has not yet happened. It might still fail. It corresponds to the "write" side of CQRS. Usually a command is written like "Create User" or "Add Node to the system".

An event, on the other hand, is the indication that a state mutation has happened. Usually it is written in past tense, like "User has been created" or "Node has been added to the system". An event is persisted in the event store, which is an append-only log of all events.

A projection reads all events and creates read-only state out of it. It corresponds to the "read" side of CQRS. When a new event comes in, the state is updated accordingly. Often, the projection state is stored in standard database tables. Projections, by nature, can always be re-created by clearing their state and applying all events (from the beginning of time) again. Basically, a projection is something like a cache.

Event Sourcing and CQRS – The Unified Model

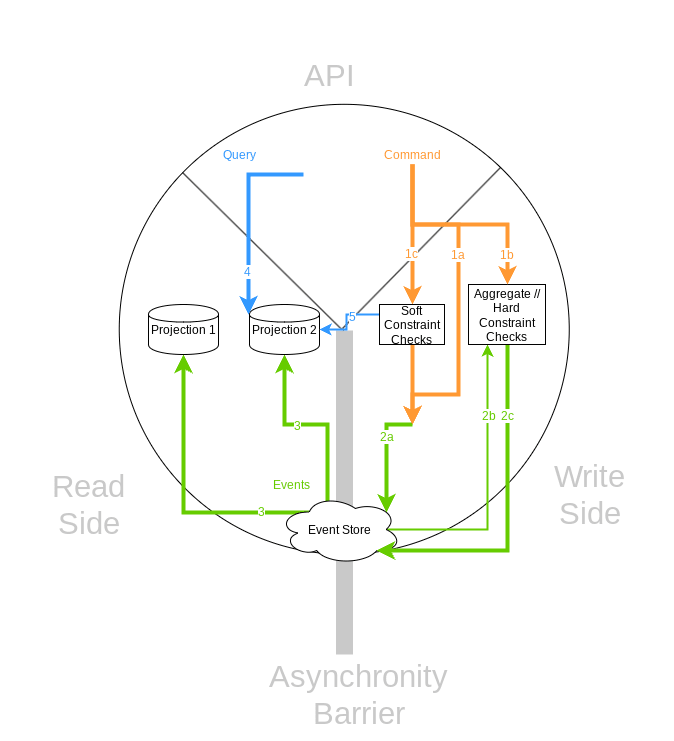

Following is a diagram which shows how CQRS and Event Sourcing work together. The diagram is split into three parts:

- On top is the external/API side of our system.

- On the right is the command side which mutates the state by generating events.

- On the left is the read side which contains different projections which can be queried.

There is inherent asynchronity through the event store. This means that when a command is executed (and stored as event in the event store), it might take some time until the projections on the read side have been updated.

1 - Simple Case - No Constraints

In the most simple case, here's what happens:

- 1a - A command is sent which can always be applied ("Update the user's last name")

- 2a - The command is directly converted to an event ("User's last name has been updated") and stored in the event store.

- (asynchronity)

- 3 - Sometimes later, the projections are updated, taking the event into account.

- 4 - Now, when the user queries the projections, he'll see the updated state.

2 - Hard Constraints - Enforced through Aggregates

Sometimes, you need to ensure that an invariant on the state is always true. For example, it might be useful to define: "It is never possible to allocate a username twice." We basically need a safeguard to ensure that the "UserCreate" command always has distinct user names. This safeguard is called an aggregate. (Do not confuse it with the term "Aggregate" in Domain-Driven-Design.) How does this safeguard work? It cannot read a projection, because this projection might be out-of-date.

Thus, an aggregate works usually in the following way:

- 1b - A command is sent to an aggregate/command handler.

- The Aggregate's state must be reconstituted so it can do its decision:

- 2b - The aggregate first receives all events which it has previously emitted from the event store.

- This way, it is able to reconstitute its state from previous events.

- Then, the hard constraint is checked; i.e. in our example it is checked whether the username is already taken.

- 2c - If the constraint is fulfilled, the event is emitted to the store.

- Otherwise, the command cannot be executed, and an error is returned.

3 - Soft Constraints - Query the read side to ensure invariants are "almost always" met

It turns out that hard constraints are not always needed; quite to the contrary: If you think hard enough about a problem, you need them quite rarely. A soft constraint, on the other hand, is not a real constraint in the sense that an invariant is always met; but it can be extremely likely that the invariant is still met. We'll cover this more in-depth later. A workflow covering soft constraints works in the following way:

- 1c - A command is dispatched.

- Before the command is transformed to an event, a soft constraint check can take place in the following way:

- 5 - We query some projection, knowing that it might not be fully up-to-date yet.

- 2a - Based on the projection result, we either accept the command and dispatch its corresponding event to the store, or we discard the command.

Consistency, Constraints and Invariants

Before we dive into which constraints should be used when, let's talk a little about consistency.

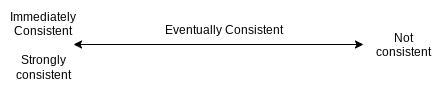

We often like to think about systems being immediately consistent (also called strongly consistent). This means that an event enters the system at a certain point in time, and everybody who accesses the system will be able to retrieve the new state directly after this event has been applied.

On the other hand, systems might be not consistent at all – this is generally a state which you try to avoid very hard; as usually you cannot easily recover back to consistent state from there.

Between systems being immediately and not consistent, there's a big space in between which is called eventually consistent. The core idea is that certain periods of time where the system is inconsistent might be acceptable, but it needs to be ensured that after "some time" (eventually) the system is consistent again. We'll explore this idea a bit further!

Eventual Consistency

So, let's explore what Eventual Consistency actually can mean. Basically, we want to ensure the system should appear as consistent as possible. "Appearing" consistent to me mostly means that a user gets a "consistent" view of what he did, i.e. when he created a comment on an article and reloads the page, he should see his comment; so we need to have a high probability that the relevant projection has already been updated.

On the other hand, it does not really matter that much when other users see the comment; it is fine if there is a delay of a few seconds (which is a long time for "eventual consistency"). It also does not matter when e.g. a search index is updated.

So, there are two tricks we can apply to make the system perceived as consistent, although "by the book" it is eventually consistent:

- We usually do not need to update all projections synchronously, but rather many can be updated asynchronously.

- When a change is visible for one user, it does not immediately need to be visible to other users of the system.

A small sidenote: Often it is suggested that a user interface should "simulate" the behavior, e.g. showing the new comment already before we got the confirmation from the server that the comment was successfully added. I personally think this is a nice trick to improve the perceived responsiveness of applications; but I still would ensure that the needed projections run mostly synchronous. Otherwise, you will get strange effects when e.g. pages are reloaded etc.

Why Soft Constraints are often sufficient

I think this is best explained with an example. In the Neos content tree, there is a "MovedNode(source, target)" event indicating that the "source" node has been moved to "target". Let's say user 1 tries to move "A" inside "B", while user 2 tries to move "A" inside "C". Thus, there's a conflict.

When I thought of preventing conflicts, I was directly thinking how a hard constraint with an aggregate could prevent this conflict. However, it might actually be not so easy enforcing this constraint with an aggregate.

Let's for a moment think what happens when a soft constraint would be applied. If two people move the same node into different directions at the same time, the soft constraint check (5 in the image above) would succeed, because the projection was not yet updated. Thus, both move events would hit the event store. Now, during projection time, we have a few options:

- We can move the node from A inside B, discarding the move of user 2

- We can move the node from A inside C, discarding the move of user 1

- We can move the node from A inside B, and then move the node from inside B to inside C (or vice versa, depending on the event ordering)

In all cases, one user will be a little confused because his change looks as if it was ignored by the system; while for the other user the end-result is the expected one. If we had hard constraints in place, then the "second" user would get an error that the move could not happen – this is unexpected for him as well. Thus, no matter whether we use hard or soft constraints, we'll always have one confused and one non-confused user in this example. Additional to that, the user whose command failed will probably just re-try his action; and chances are extremely high that the user's action will now work. (Unless, of course, another user moves the node again at exactly the same time :-) ). Thus, why should you use a hard constraint here if it has roughly the same experience for your end-user than when using a soft constraint?

To sum it up, soft constraints are important because they catch the common case. They ensure your system is perceived as being consistent. They make it extremely likely that the system behaves predictable for your users.

Often, you'll find very few cases where compensating an error would be very costly; these are usually good candidates for hard constraints. Then, try to create aggregates, where each of them should only care for one of these constraints.

Soft constraints catch the common case. They ensure your system is perceived as being consistent.

Implementation Details

Here are some further implementation details which are important on a detail level:

- As already stated, try to reduce the number of hard constraints as much as possible.

- Treat your aggregates as implementation details of the write side. They are just very strong constraint checkers, after all.

- Name your aggregates after the invariants they protect. Call them UserUniquenessAggregate instead of UserAggregate.

- If one aggregate becomes too imperformant, you can often partition these further; e.g. have one UserUniquesAggregate per first-character of the user name.

- Soft constraints should be checked inside your command pipeline [I still dislike this name]; e.g. before the command is converted to an event and persisted in the event store.

There's one topic which I did not cover at all yet, but which is important for many real-world applications: The concept of a Process Manager. Basically, a process manager listens to emitted events (pretty much just like a projection); and can react to events by emitting new commands. They allow to encapsulate side-effects, such as accessing configuration or getting the current system time. Furthermore, they allow to orchestrate bigger flows, pretty much like React Redux Sagas.

How we'll use all this in the Neos Content Repository

This article covers my thinking and mindset which I currently use to approach the Neos Content Repository domain. It is not showing yet the specifics we want to use to apply the CQRS / Event Sourcing methodology. This is the topic for another blog post!

PS: All views expressed here are my own; and of course, all errors and misunderstandings as well – @mathias

- I hope there are not too many of them in here :-)

PPS: This is a cross-post of my post at our company blog

Posted on January 1, 2019

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.