Why I'm Digging Eleventy

Raymond Camden

Posted on October 14, 2019

It’s been quiet around here lately and for that I apologize. Between the new job and a bunch of trips and presentations, I’ve not had much time for exploration. Next week I’m giving a presentation at connect.tech on static sites (The Platform Formally Known as Static). It’s been a while since I presented on static sites (the JAMStack) so I’ve been updating my slide deck in preparation. When I present on the JAMStack, I typically focus on one particular engine to give folks a “feel” for what it’s like to work with static sites. On a whim, I decided I’d give Eleventy a try. I’ve been hearing about it for a while and thought it would be nice to do a bit of research.

One of the things I’ve found is that I either love a static site generator or hate it. These apps tend to be very opinionated about how they do things and if you don’t like their opinion then it’s not fun to work with them. I love the JAMStack but there’s only a few generators that I enjoy working with.

While it’s still rather early (I’ve been looking at Eleventy for a grand total of about three days), I’m absolutely blown away by Eleventy. Why?

Built on Node

My current favorite generator is Jekyll. I really like it. However it’s built on Ruby and getting it to work on Windows has been, at times, hellish. I’ve got nothing against Ruby in general, but it’s not a platform I’m familiar with and I’ve never worked with the SDK before. I got a new laptop about two months ago and I was dreading getting Jekyll up and running on it. I knew once I did I’d be fine, but I was not looking forward to the process.

To be fair, it actually went OK. The main issue I had was that Jekyll 4 came out recently and upgrading caused me a bit of trouble. (Maybe 1-2 hours of work, so not really that bad.) Also, you don’t need to know Ruby at all to be successful with Jekyll. I’ve written one custom plugin for Jekyll in the year I’ve used it, but outside of that, the Ruby language isn’t a concern for me.

That being said, the fact that Eleventy is built on Node is a big plus for me. It’s a platform I know well, I’m comfortable with, and know will work reasonably well on any platform, even my “Linux on Windows” platform with WSL.

Multiple Template Languages

I enjoy working with template languages, some more than others. Eleventy gives you 11 (oh my god, I just noticed that) different templating options. That’s a huge amount of variety and you can pick the one that works best for you. For example, they support Handlebars, and while I like Handlebars, it can be a bit too strict at times for me. It also supports Liquid, which is the template language Jekyll uses, so I can re-use my existing skills.

You’re also free to mix and match languages as you see fit. So for example, you can use Markdown (which also lets you use Liquid inside it) for content and then Liquid for your layouts.

Simple

While there is a huge amount of customization and power behind Eleventy, it is also incredibly easy to get started with. You can take one markdown file, run the CLI, and get an HTML file out. If you aren’t worried about layouts or other features, you can take source files and immediately generate HTML output. The default behavior of Eleventy covers most use cases but you also have deep configuration options for tweaking how it behaves.

Customizable to the Extreme

As stated above, there’s a rich configuration API to modify how Eleventy behaves. The part that I think is really need is how Eleventy provides hooks into the various template languages. Things like Handlbars helpers for example. In a typical Node.js application, you would load in Handlebars, add your helpers, and get to work. Because Eleventy loads up the engines for you behind the scenes, that isn’t an option. Instead, they provide an API to directly add stuff (like helpers, and more) to your engine.

So pretend I’m using Handlebars and want to build an uppercase helper to use for the following template.

---

name: ray

---

Hello {{ upper name }}

To make this work, I’d add a .eleventy.js file in the root of my folder, and then use the following:

module.exports = function(eleventyConfig) {

eleventyConfig.addHandlebarsHelper("upper", function(value) {

return value.toUpperCase();

});

};

And that’s it. But holy crap - it gets better. Eleventy actually supports adding stuff to multiple engines at once. While this isn’t supported across all 11 templating engines, you could change the code above to:

module.exports = function(eleventyConfig) {

eleventyConfig.addFilter("upper", function(value) {

return value.toUpperCase();

});

};

This adds the helper (called a filter to Eleventy) to Liquid, Nunjucks, and Handlebars.

Another example of the flexibility comes with permalinks. Most engines provide a way to change the default “source file to output file” logic. Eleventy allows this too, and is really useful in cases where you want to output non-HTML files. So for example, I could have a data.json.liquid file. By default Eleventy will output this to /data.json/index.html. This normally makes sense for HTML files. In this case, I can change the output like so:

---

permalink: data.json

---

This particular use case is one of the reasons I stopped using Hugo for my blog. Hugo was incredibly fast (although not much faster than Jekyll 4) but it felt like anything non-HTML related was a pain. I remember spending hours trying to get Hugo to output JSON and I simply gave up. That could been my fault (most likely it was), and I know they have support for this use-case, but I could never get it to work properly. Hugo felt incredibly strict about how it worked and I’m glad I left it.

As an FYI, permalinks can also have variables in them. This allows for dynamic outputs.

Data Support

All static site generators support “data” in some form. This is a way to define information that can be used in templates when generating static output. Eleventy is very flexible in this regards as well.

- It obviously supports front matter, both for templates and layouts.

- Data can also be specified for a particular file. This lets you associate information with one particular template and help keep it a bit cleaner by having separation between the layout and the data.

- Data can also be associated with a directory, and subdirectories.

- Data can also be global.

- Front matter data is typically YAML (although it doesn’t have to be in Eleventy), but for data files you can use both JSON and JS.

That last point is really, really cool. Why? Because you can actually use async data for your static site. Imagine the following script in _data\films.js:

const fetch = require('node-fetch');

module.exports = async function() {

let resp = await fetch('https://swapi.co/api/films/');

let films = await resp.json();

return films.results;

};

This simply hits the Star Wars API to return a list of films. Now my templates can do this:

## Star Wars Films

{% for film in films %}

* {{ film.title }}

{% endfor %}

And by the way, when I first tried this, I forgot to install node-fetch, Eleventy recognized this very quickly and gave me a nice error in the console. In general, when I’ve screwed things up, Eleventy has been great about providing information. In code like the above, you can also use console.log to help debug.

The Final Reason

Alright, so I was sold on Eleventy before I discovered this, but this final reason is what really, really impressed me. There isn’t a good name for the problem I’m about to describe, but it’s a common issue with static site generators.

Consider the example code above where I wrote some code to load data and return a dynamic set of Star Wars films. I then rendered it in a list in a template. But what if I wanted to do a “detail” view? In an app server, I’d simply link to a detail page and pass an ID value, so for example, I may use a URL like this in a Node application: /film/3. The 3 represents the primary identifier for the film. I’d use logic in my handler for film to render the right result.

In a static site, you would need something different typically. Given 3 films, you may need output like so:

/film/1/index.html

/film/2/index.html

/film/3/index.html

However, most static site generators require a “one to one” correlation between input files and output files. In the past I’ve solved this in a variety of ways. One way is with a script that reads in the data, generates stub files, each of which will then include a core layout file to render the detail.

Eleventy solves this issue in what I consider to be the most awesome, and simple, way possible. Eleventy has a Pagination API that I initially ignored. I saw the feature and thought, ok, given N blog posts, this helps me build N/10 pages of blog listings. And yes, it does that (and does it damn well), but, it also handles the use case above.

So imagine I have an array of data, films, and I want go generate one file each. I could use the following file I’ve named film.liquid:

---

pagination:

data: films

size: 1

alias: film

permalink: films/{{ film.title | slug }}/index.html

---

{{ film.title }} was released in {{ film.release_date }}

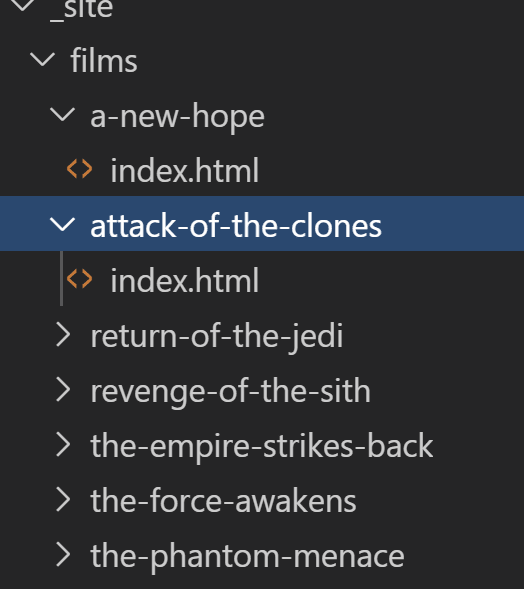

THe front matter defines that I want pagination, that I want to iterate over films, and that I want one data item per file. Now check out the permalink. It specifies that I should take the title of the film, pass it via a “slug” filter (this is built into Eleventy), and store it there. The code beneath the front matter is how I render the film.

And that’s it. As I said… holy crap. Here’s how the output looks:

Want to Learn More?

So this wasn’t meant to be a “Intro to Eleventy” post. As the title says, I wanted to explain why I’m so darn impressed by what I’ve seen. I highly encourage you to take a look at the docs to learn more. I don’t see myself immediately rebuilding my site in Eleventy, I just updated the UI less than a year ago I think. But it will absolutely be the next generator I use. I’m also tinkering around some blog posts demonstrating how to use it more fully. (As I said above though, it’s been tough to find time lately.) If you are using it currently, leave me a comment. Or - if you looked at it and decided against it, I’d love to hear why as well.

Header photo by Dominik Schröder on Unsplash

Posted on October 14, 2019

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.