Javascript Objects Deep Dive: References, Primitives, Equality, Immutable, Tree and Circular

Rafael Calpena

Posted on June 28, 2020

Objects are a fundamental block for creating application state. Therefore, it's essential to understand how they work and what their manipulation strategies are.

Note: This article makes assumptions based on the way objects are handled in Javascript. Programming languages differ slightly on the topic, but many of the concepts covered below can be applied to your language of choice.

Variables and Memory

Our programs need to store, read and possibly modify data while running. Hence, there's a need to reach previously defined values in our code for later use. With Javascript, that can be done with variables:

let welcomeMessage = 'Hello World';

let age = 38;

let hungry = true;

Let's use a simplified analogy to represent what's going on under the hood. There are 2 tables of correspondence:

- First table relates memory addresses to their current values. The number of addresses depend on the size of the available RAM in the machine.

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 001 | 'Hello World' |

| 012 | true |

| 043 | 38 |

- Second table relates variable names to memory addresses. These are the variables declared in our program.

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| welcomeMessage | 001 |

| age | 043 |

| hungry | 012 |

💡 Memory address indexes do not necessarily have a pattern.

References

See those memory address codes in the table (001, 043, 012)? We will call them References from now on. They're the physical address in memory where values are being stored.

Important: References are NOT variable names. Rather, variable names are pointing to a reference. That's an important distinction we have to make in order to understand the next concepts.

Reading Some Variable

In order to read some variable (for example, age), the program will obtain its specific memory address (reference), and then its value:

age -> 043 -> 38

Immutability

Think about creating a payment check to someone. Once we are done writing it, we expect it to remain unchanged. That's the reason we use pens (no removals) and cross-out void spaces (no additions).

What if the check had been misspelled?

In that case, it's a better idea to write a new check instead of overwriting the current one, shred the current check and throw it away in the garbage.

We are about to see that Immutability is also used in many programming scenarios, often due to the same reason (guaranteeing consistency).

Primitives

a primitive (primitive value, primitive data type) is data that is not an object and has no methods.

According to MDN Web Docs, Javascript contains 7 primitives: string, number, bigint, boolean, undefined, symbol and null.

We can consider Primitives one the lowest building blocks in the language. It's important to note that they have no methods.

I can call

.toString()on a number, doesn't that mean it has properties/methods?

Not really. Javascript applies Autoboxing to primitives. One quick way to check this is to try creating a new property in the number:

let myNumber = 345;

myNumber.previousNumber = 344;

myNumber.previousNumber //undefined

If they did have properties, previousNumber would have been saved in the example above.

Primitives are Immutable

One important characteristic of primitives is that they do not allow for modifications after they are created.

Primitives are written with pens.

What does Immutable mean in programming terms, though? Going back to our memory analogy:

let myCoolPrimitive = 'This is a primitive';

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 047 | 'This is a primitive' |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| myCoolPrimitive | 047 |

The value inside Reference 047 is immutable. It cannot be altered anymore. So how to change the value for myCoolPrimitive?

let myCoolPrimitive = 'This is a primitive';

myCoolPrimitive = 'Can I change it though?';

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 047 | 'This is a primitive' |

| 019 | 'Can I change it though?' |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| myCoolPrimitive | 019 |

The reference has been updated to a new string.

Let's also use an example with 2 variables this time:

let firstPrimitive = '1st primitive';

let secondPrimitive = firstPrimitive;

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 001 | '1st primitive' |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| firstPrimitive | 001 |

| secondPrimitive | 001 |

/* ...Continuing code from snippet above */

secondPrimitive = 'Changed to second primitive';

console.log(firstPrimitive) // '1st primitive'

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 001 | '1st primitive' |

| 002 | 'Changed to second primitive' |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| firstPrimitive | 001 |

| secondPrimitive | 002 |

Only the targeted variable (secondPrimitive) will change its value.

Objects

If some value is not a primitive, then it is an object.

JavaScript objects are containers for named values, called properties and methods.

Source: W3Schools

Examples of objects include (but are not limited to): {}, [], Function, Date, HTMLElement, Set, Map, etc.

Objects are written with pencils

Unlike primitives, one can create an object and modify its properties later. That's mutable behavior, let's see an example:

let user1 = {name: 'Josh', credit: 200};

let selectedUser = user1;

let creditVar = user1.credit;

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 001 | {name: $002, credit: $003} |

| 002 | 'Josh' |

| 003 | 200 |

💡 Object properties point to memory addresses. $ notation represents a reference.

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| user1 | 001 |

| selectedUser | 001 |

| creditVar | 003 |

user1.credit = 600;

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 001 | {name: $002, credit: $004} |

| 002 | 'Josh' |

| 003 | 200 |

| 004 | 600 |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| user1 | 001 |

| selectedUser | 001 |

| creditVar | 003 |

console.log(selectedUser.credit) //600

console.log(creditVar) //200

- Credit Number got updated, it's a primitive so it created a new reference (

$004). -

The object was updated after it's creation (updated credit number reference from

$003to$004). Therefore, it is showing mutable behavior. -

selectedUseranduser1are pointing to the same object. They are sharing the object and its properties, and if one variable updates a property, the other variable will also reflect the changes. -

creditVarnever got updated to 600 because it's pointing to the 200 primitive that was previously defined.

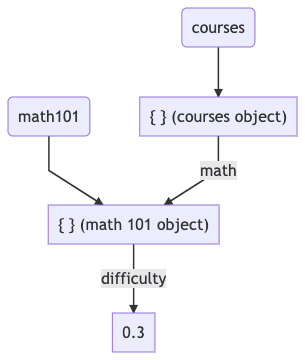

Objects Inside Objects

It's also possible to "nest" objects.

let math101 = {difficulty: 0.3}

let courses = {math: math101}

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 001 | {math: $002} |

| 002 | {difficulty: $003} |

| 003 | 0.3 |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| math101 | 002 |

| courses | 001 |

Circular Objects

It's possible to reference one object to itself as a property.

let a = {};

a.b = a;

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 001 | {b: $001} |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| a | 001 |

It's also possible to reference 2 or more objects in a circular way.

let o1 = {};

let o2 = {};

o1.o2 = o2;

o2.o1 = o1;

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 100 | {o2: $101} |

| 101 | {o1: $100} |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| o1 | 100 |

| o2 | 101 |

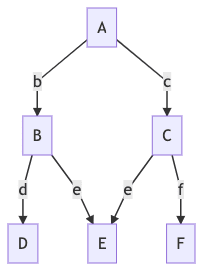

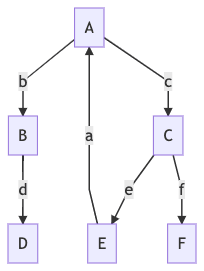

Object Tree

An Object Tree is a specific type of object that contains child objects where:

- An object can only appear once in the tree (0 or 1 incoming edges).

- There are no cycles in the graph.

This is a valid example of an Object Tree

Invalid example (E has 2 parent objects)

Invalid example (Graph contains cycle A -> C -> E)

Garbage Collection

You may have noticed in our examples that values can stay in memory even after they're not being used by any other variables (or objects). Fortunately Javascript comes with a Garbage Collector, which periodically wipes away unreachable values automatically, so we don't have to worry about explicitly deleting them from memory:

let someVar = 123;

someVar = "Now I'm a string!";

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 001 | 123 |

| 002 | "Now I'm a string" |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| someVar | 002 |

After Garbage Collection, Address 001 should be released:

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 002 | "Now I'm a string" |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| someVar | 002 |

Garbage Collection is dependent on the environment's implementation (Browser, Node.js, etc), but generally uses the "Mark-and-sweep Algorithm", according to this MDN Article about Memory Management

Equals Operator

NOTE: As a rule of thumb, use Triple Equals Operator (===) when possible instead of (==). See why here

In Javascript, the equals operator works differently for primitives and non-primitives:

let firstString = 'The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog';

let secondString = 'The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog';

console.log(firstString === secondString) // true

let firstObject = {};

let secondObject = {};

let thirdObject = secondObject;

console.log(firstObject === secondObject) //false

console.log(secondObject === thirdObject) //true

| Address | Value |

|---|---|

| 001 | 'The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog' |

| 002 | 'The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog' |

| 003 | {} |

| 004 | {} |

| VarName | Address |

|---|---|

| firstString | 001 |

| secondString | 002 |

| firstObject | 003 |

| secondObject | 004 |

| thirdObject | 004 |

When comparing 2 variables with ===:

Primitive Values will return

truewhen their content is the same (even if memory addresses are different for each variable!)Objects will return

trueonly if the 2 variables point to the same memory address.

Comparing 2 objects deeply (by their content instead of reference) is often not desired since it can be computationally expensive and unpredictable (depends on the depth and key length of the objects). That being said, in extreme cases it's recommended to use some library method, for example Lodash's isEqual function

Immutable Objects

Avoiding Side Effects

Sharing the same object is a performance improvement (less memory is allocated). But there are times when you need independent copies. One example is extending from a base object.

In order to create Immutable objects, We can use spread operators for Arrays ([...]) and Objects ({...})

💡 Remember: The new object should behave as "read-only" after being cloned and applied the desired changes. If subsequent changes are needed, a new immutable object should be created. This will guarantee the object consistency promised by the immutable strategy.

let baseCar = {

color: 'black',

convertible: false,

passengers: 5

}

let fancyCar = {...baseCar, convertible: true}

/* {

color: 'black',

convertible: true,

passengers: 5

} */

By creating different references, we can be sure that the baseCar will not be altered when there is a change in fancyCar. This avoids side-effects in our code.

Benefits Of Immutability

By using the concept of Immutable objects we can better integrate our code with features like:

-

Faster Change Detection: Updates often change only part of an object. By using

===operator (fast), deep object comparison is possible by using references, avoiding expensive full object traversal (e.g. Lodash's isEqual).If

newObject !== oldObject, something changed. We can recursively inspect its properties and find the changed values faster. "Time Travel": Previous versions of objects can be kept in memory. Each version is a snapshot of the object, which allows for inspection through time and helps to debug the code.

Nested Immutable Updates

Updating a nested object Immutably is relatively simple when your Object structure is a Tree. All we have to do is use the spread syntax in all the levels preceding the property.

Let's update obj.a.b.c immutably to false in the example below:

let obj = {

a: {

b: {

c: true,

e: 'mnop'

},

d: 456

}

y: {

z: 12

}

}

let obj2 = {

...obj, //Copy obj properties

a: { //Overwrite property obj.a

...obj.a, //Copy obj.a properties

b: { //Overwrite property obj.a.b

...obj.a.b, //Copy obj.a.b properties

c: false //Overwrite obj.a.b.c property

}

}

}

The resulting object contains all properties defined in obj, with the update on obj.a.b.c = true. Notice only the changed objects have been cloned, so we can still use reference equals operator for unchanged properties:

obj.a === obj.a; //false

obj.y === obj2.y; //true

This is great for both cloning and equality check performance.

Complex Immutable Updates and Improvements

Is it possible to improve copying performance of nested objects when batching updates?

How to update nested immutable objects when they are not in the shape of a tree? How do multiple parents and object cycles interfere with our workflow?

These questions are harder to answer and will be covered in the next part of our series. Thanks for reading and stay tuned for the following chapters :)

Posted on June 28, 2020

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.

Related

June 28, 2020