Paula Gearon

Posted on August 22, 2022

I have recently been working with graph databases again, and with OWL descriptions of information. This isn't just about a graph of information, but also about how the information is structured. It's similar to a schema in an RDBMS, but with more information.

Describing data in a graph and ontology uses a mathematical system called Description Logic (DL). In fact, it was a community of Description Logic researchers who came together to develop the OWL standard. The result is a system that can be obtuse to learn, but has a solid mathematical foundation without "bugs".

It also has the ability to do some unexpected things.

Oedipal Issues

There is an example provided in the Description Logic Handbook, referred to therein as the "Oedipus Problem". (See page 73 of this PDF of the 1st edition) A set of relationships around the mythical figure of Oedipus is described using DL, and then a complex question is asked that appears unanswerable at face value.

To start with, let's look at the DL data that is presented:

hasChild(IOKASTE, OEDIPUS)

hasChild(IOKASTE, POLYNEIKES)

hasChild(OEDIPUS, POLYNEIKES)

hasChild(POLYNEIKES, THERSANDROS)

Patricide(OEDIPUS)

¬Patricide(THERSANDROS)

This describes a rather messy family tree.

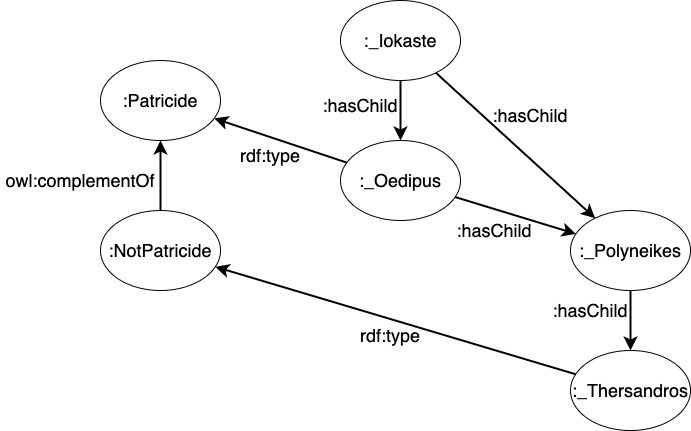

Oedipus is colored a light red to indicate that he killed his father (ie. he is a "Patricide"), while Thersandros is light blue to indicate that he did not kill his father (he is not a Patricide).

Each statement in the DL is presented as a "predicate". This is some kind of name followed by parentheses. The first one here is hasChild. Because it has 2 elements inside the parentheses, then it represents something called a role. The first line says that IOKASTE is connected by the role of hasChild to OEDIPUS, and you can see that I've indicated this in the diagram. By convention, roles will always start with a lower-case letter.

The last two lines have only a single element in the parentheses. These declare the class of something. The first one says that OEDIPUS is in the class of Patricide. This is just using DL syntax to describe that he killed his father. The second uses an operator that inverts the class, saying that THERSANDROS is in the class of anyone and anything that is not a Patricide. Again, this is using DL to explicitly state that Thersandros did not kill his father.

A Box

The data presented so far is what is referred to as instance data. The formal term for this is the ABox, which stands for "Assertion Box". This is like the data that might be found inside a table in an RDBMS.

This ABox contains 4 statements of hasChild, and 2 type statements: membership in the Patricide class, and membership of the class that indicates not-a-Patricide, which is indicated as the class of things that is everything that is not a Patricide.

T Box

What does not appear here is the ontology of the data, which is formally known as the TBox or "Terminology Box". This is similar to a database schema but also goes on to describe relationships between entities, relationships between relationships, properties of relationships, and more.

While the TBox has not been included, we can infer a little from the ABox:

- We can see that there is a relationship called

hasChildthat connects elements in the domain. - We can see that these elements can be on either side of those relationships.

- There is a class called

Patricide. - Elements may be a member of

Patricideor not. This indicates that those elements that are members ofPatricideform a subset of the full domain of elements. We see this becauseTHERSANDROSis an element, but is not aPatricide.

Open World

Consider how Thersandros is being explicitly declared as not being a member of the Patricide class. This is a result of the Open World Assumption (OWA), and may seem unusual when compared to the more common Closed World Assumption (CWA).

In the CWA, any data that is not explicitly stated is known to be false. For instance, both Iokaste and Polyneikes are not declared to be in the class of Patricide, and in the CWA this implies that they are not members of this class. The statement about Thersandros not being a Patricide would therefore be redundant. Most programming systems and databases work on this assumption, so developers are usually familiar with this paradigm.

In contrast, under the Open World Assumption any data that is not stated is instead unknown. At some point in the future, more information may be explicitly provided, or a reasoning process may determine new information. But until then, it is not valid to make any decisions based on unstated data.

The ¬Patricide(THERSANDROS) statement has been made under the OWA, so that we explicitly know that Thersandros is not in the Patricide class. We also know that Oedipus is a member of that class. But we have no information about whether Iokaste and Polyneikes are members.

The Question

The question that is posed is this:

Does IOKASTE have a child who is a Patricide, who, in turn, has a child who is not a Patricide?

This question can be posed in Description Logic with the expression:

(∃hasChild.(Patricide ⊓ ∃hasChild.¬Patricide))(IOKASTE) ?

For those who don't know the terminology, let's break it down, by using some substitution.

The expression:

Aoe(IOKASTE) ?

is asking if IOKASTE is a member of the class Aoe. We can then define Aoe as the class in our question:

Aoe ≡ ∃hasChild.(Patricide ⊓ ∃hasChild.¬Patricide)

(The ≡ symbol means "is equivalent to")

So now we need to break down the Aoe class. Let's substitute for the compound statement:

Aoe ≡ ∃hasChild.B

B ≡ Patricide ⊓ ∃hasChild.¬Patricide

This redefines Aoe in terms of B. This definition says that to be a member of Aoe an entity must have a hasChild relationship to an entity that is of type B. Breaking down B, we come to:

B ≡ Patricide ⊓ C

C ≡ ∃hasChild.¬Patricide

So to be a member of the B class, an entity must be both an instance of the Patricide class, and also the C class. The C class is actually compound, but small enough that I did not break it up further. This class defines an entity that has a child that is not a member of the Patricide class.

Solving for Aoe

To see if IOKASTE is a member of Aoe we can look to see if there is a hasChild relationship, and if one of those children is a member of the B class defined above.

IOKASTE has 2 children: OEDIPUS and POLYNEIKES. Let's consider each in turn.

The Oedipus Child

For OEDIPUS to be a member of B, he needs to be a Patricide and to be a member of C. OEDIPUS is declared as a Patricide, so now we consider he is a member of the C class. This requires a hasChild relationship to someone who is not in the Patricide class.

In this case, there is a hasChild relationship to POLYNEIKES, but there is no information to indicate if POLYNEIKES is a Patricide or not. This means that we cannot determine if the conditions are met.

Note that we have not determined that IOKASTE is not a member of Aoe. We just do not have sufficient information. POLYNEIKES is either a member of Patricide or she is not, and this will determine whether IOKASTE is a member of Aoe. If POLYNEIKES is not a member of Patricide, then the condition of Aoe(IOKASTE) will be met.

The Polyneikes Child

For POLYNEIKES to be a member of B, she needs to be a Patricide and to be a member of C. We don't know if she is a member of the Patricide class or not, but let's consider the C class.

To be in the C class, POLYNEIKES requires a hasChild relationship to someone who is not in the Patricide class. In this case, there is a hasChild relationship to THERSANDROS who is explicitly declared to be not in the Patricide class. So POLYNEIKES is indeed in the C class.

In this case, we also don't know if IOKASTE is a member of Aoe. Again, this is solely dependent on whether or not POLYNEIKES is a member of Patricide.

Solution

At face value, it appears that there is no way to answer the question of Aoe(IOKASTE), since all possible paths have an unknown element.

However, for the path through OEDIPUS, we know that Aoe(IOKASTE) is true if and only if ¬Patricide(POLYNEIKES). Meanwhile, for the path through POLYNEIKES, we know that Aoe(IOKASTE) is true if and only if Patricide(POLYNEIKES).

Patricide(POLYNEIKES) may only be true or false, meaning that Polyneikes is a member of the class or she isn't. There aren't any other possibilities. And since both possibilities result in Aoe(IOKASTE) being true, then this tells us that the condition is met.

The unusual thing here is that we don't know how the condition is met. We don't have complete information, but we do have enough information to show that the condition is true regardless of the unknown state.

Without Rules

A forward-chaining reasoner is one that relies on modus ponens and modus tollens. These are both mechanisms that take known information, and deduce new information. However, for the problem of determining Aoe(IOKASTE), the solution is arrived at through unknown state, meaning that forward-chained reasoners are unable to deduce the result.

Theoretically, in a limited case like this, it is possible to create rules for the solution. For instance, a predicate might be created that indicates "true, if X is true", or "true, if X is false", and then create a rule that returns true if both of these are asserted. However, this is limited to simple conditions on single variables. The constructs would quickly get unwieldy as the number of variables increased, and the possible states would explode combinatorially with many of these conditional predicates being asserted.

Rather than rules that create conditional assertions, logic engines like Prolog can explore these possibilities in memory. This can and does work, but this approach may also have difficulty in scaling as the number of states increases, and the logic engine has to search them all.

What I have discussed so far are proof procedures based on Natural Deduction and trees. Another approach is using a Semantic Tableaux. This considers the entire TBox as a series of logic expressions, along with the inverse of a statement that is being evaluated. The process then manipulates the logic expressions until the statement can be "proven". If it is shown to be false then the inverse was true, so the statement to be evaluated is true.

Let's get this back into concrete implementations.

RDF

The Resource Description Framework (RDF) is a graph data model, where each edge may also be considered to be a logic assertion of a binary predicate applied to each of the connected nodes.

For instance, a graph containing 2 nodes of A and B with a edge of E between them would appear as:

The logic representation of this is where the edge is considered a binary predicate:

E(A, B)

Unary predicates in description logic are a statement of an entity's type, and so RDF has created a specific predicate called rdf:type to represent this. For instance, saying that Oedipus is a Patricide has the logic representation of:

Patricide(OEDIPUS)

And appears in the RDF graph as:

This covers most of the ABox that was declared for the Iokaste problem, with the exception of Thersandros being declared as not being a member of Patricide.

OWL

While RDF is adequate for the ABox data, it is the TBox with its complex class descriptions that describes the question we are trying to answer. The Web Ontology Language (OWL) is a language that includes these descriptions, and is specifically designed to work with RDF data. OWL itself can be serialized into RDF and stored in a graph alongside the data it is describing.

Serializing in TTL

Using RDF and OWL, the complete ABox as well as the ¬Patricide class can be described in RDF, and serialized into a text format. I prefer to use the Terse Triples Language (Turtle) to serialize RDF, though several other formats exist.

@prefix : <http://demo.imo.com/oedipus#> .

@prefix owl: <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#> .

:NotPatricide owl:complementOf :Patricide .

:_Iokaste :hasChild :_Oedipus ,

:_Polyneikes .

:_Oedipus :hasChild :_Polyneikes ;

a :Patricide .

:_Polyneikes :hasChild :_Thersandros .

:_Thersandros a :NotPatricide .

This looks like the following:

Back to the Question

With this data in place, I ask about the Aoe class defined above if I add that class to my graph:

:Aoe owl:equivalentClass [

a owl:Restriction ;

owl:onProperty :hasChild ;

owl:someValuesFrom [

owl:intersectionOf (:Patricide

[a owl:Restriction ;

owl:someValuesFrom :NotPatricide ;

owl:onProperty :hasChild])]] .

This is a transliteration of the expression:

∃hasChild.(Patricide ⊓ ∃hasChild.¬Patricide)

into OWL, and was done using the serialization rules shown in the OWL2 Quick Reference Guide.

Reasoning

We can ask if Iokaste is a member of the Aoe class by using a SPARQL ASK query, with reasoning turned on:

@prefix : <http://demo.imo.com/oedipus#> .

ASK { :_Iokaste a :Aoe }

If we load this into an RDF database and issue the query we will get a result of: false

What? This took so long to get here! What went wrong?

The answer is that we need to enable reasoning. Not every database can handle this, and even fewer can deal with reasoning around incomplete data.

Stardog

To see a database that can manage this, let's look at Stardog. This is a commercial database, but it can be used for free on smaller datasets. Installation is well documented, and then the web-based UI is very capable, with lots of useful features (that can take a while to explore). Connecting to this UI link requests the address of your DB, connects into it, and gives you an easier interface than a command line.

Try putting the above ABox and definition of :Aoe into a file called oedipus.ttl, then it can be loaded into a new database that we will also call "oedipus":

$ stardog-admin db create -n oedipus oedipus.ttl

This should have an output like:

Bulk loading data to new database oedipus.

Loaded 19 triples to oedipus from 1 file(s) in 00:00:00.337 @ 0.1K triples/sec.

Successfully created database 'oedipus'.

Now try looking at the data:

$ stardog query execute oedipus 'select ?s ?p ?o {?s ?p ?o}'

+----------------------------------------------------+---------------------+----------------------------------------------------+

| s | p | o |

+----------------------------------------------------+---------------------+----------------------------------------------------+

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61818 | owl:someValuesFrom | :NotPatricide |

| :_Thersandros | rdf:type | :NotPatricide |

| :NotPatricide | owl:complementOf | :Patricide |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61816 | rdf:first | :Patricide |

| :_Oedipus | rdf:type | :Patricide |

| :Aoe | owl:equivalentClass | _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61814 |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61814 | rdf:type | owl:Restriction |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61818 | rdf:type | owl:Restriction |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61814 | owl:onProperty | :hasChild |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61818 | owl:onProperty | :hasChild |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61815 | owl:intersectionOf | _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61816 |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61816 | rdf:rest | _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61817 |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61817 | rdf:first | _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61818 |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61817 | rdf:rest | rdf:nil |

| _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61814 | owl:someValuesFrom | _:bnode_5f51466d_e100_4b91_b2ea_cf0a9bbc5477_61815 |

| :_Iokaste | :hasChild | :_Oedipus |

| :_Iokaste | :hasChild | :_Polyneikes |

| :_Oedipus | :hasChild | :_Polyneikes |

| :_Polyneikes | :hasChild | :_Thersandros |

+----------------------------------------------------+---------------------+----------------------------------------------------+

Query returned 19 results in 00:00:00.257

If we trace through all of these statements, we can see the blank nodes that were created in the construction of the :Aoe class, along with the intersection list and the restrictions.

Enable Reasoning

When reasoning is enabled, the TBox is used to describe the data, and direct the reasoning. Consequently, none of the TBox information should appear in the output. We see how this looks on the oedipus data by adding a -r flag:

$ stardog query execute -r oedipus "select ?s ?p ?o {?s ?p ?o}"

+---------------+-----------+---------------+

| s | p | o |

+---------------+-----------+---------------+

| :_Iokaste | :hasChild | :_Oedipus |

| :_Iokaste | :hasChild | :_Polyneikes |

| :_Oedipus | :hasChild | :_Polyneikes |

| :_Polyneikes | :hasChild | :_Thersandros |

| :_Oedipus | rdf:type | :Patricide |

| :_Thersandros | rdf:type | :NotPatricide |

| :_Iokaste | rdf:type | owl:Thing |

| :_Oedipus | rdf:type | owl:Thing |

| :_Polyneikes | rdf:type | owl:Thing |

| :_Thersandros | rdf:type | owl:Thing |

+---------------+-----------+---------------+

Query returned 10 results in 00:00:01.313

This is easier to follow, but the only new data is that all the instance data now has the type owl:Thing. That's correct, but not particularly interesting. And it doesn't infer any members for :Aoe.

Stardog can use different reasoning levels, and by default it uses a combination of RDFS, OWL QL, OWL RL, and OWL EL. This is very powerful, but it still doesn't handle the incomplete information from the Oedipus example. However, Stardog also supports the Pellet reasoner. This reasoner is fast and capable, though it can be limited in the scale that it can manage. Fortunately, our data set is tiny so that won't be a problem.

To switch to the Pellet reasoner, the database has to be taken down and then back up with the new reasoner setting:

$ stardog-admin db offline oedipus

The database oedipus is now offline.

$ stardog-admin metadata set -o reasoning.type=DL -- oedipus

The option(s) for the database 'oedipus' were successfully set.

$ stardog-admin db online oedipus

The database oedipus is now online.

Now we can look at the data again:

$ stardog query execute -r oedipus "select ?s ?p ?o {?s ?p ?o}"

+---------------+-----------+---------------+

| s | p | o |

+---------------+-----------+---------------+

| :_Oedipus | :hasChild | :_Polyneikes |

| :_Iokaste | :hasChild | :_Oedipus |

| :_Iokaste | :hasChild | :_Polyneikes |

| :_Polyneikes | :hasChild | :_Thersandros |

| :_Oedipus | rdf:type | :Patricide |

| :_Iokaste | rdf:type | :Aoe |

| :_Oedipus | rdf:type | owl:Thing |

| :_Thersandros | rdf:type | owl:Thing |

| :_Iokaste | rdf:type | owl:Thing |

| :_Polyneikes | rdf:type | owl:Thing |

| :_Thersandros | rdf:type | :NotPatricide |

+---------------+-----------+---------------+

Query returned 11 results in 00:00:00.303

This includes a single new statement, saying :Aoe(:_Iokaste)

Now we can ask the original question:

$ stardog query execute -r oedipus "ASK {:_Iokaste a :Aoe}"

Result: true

Conclusion

This post explored description logics, and how they can be used to reason on incomplete data. It also demonstrated how the Web Ontology Language is used to encode Description Logic, and how this, in turn, can be represented as RDF. Finally, we used Pellet as an OWL reasoner to answer the original question.

Afterword: The above link for Pellet is to a paper in the Journal of Web Semantics. The system itself is open source and can be found on Github.

Next

I discuss more of modeling data in RDF/OWL in my next post...

Posted on August 22, 2022

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.