Exploring how to use the Law of Demeter

Dylan Maccora

Posted on June 28, 2020

First and foremost I should define exactly what the Law of Demeter is. The Law of Demeter is a design principle of object orientated software, which is also known as the principle of least knowledge. The essence of the principle is that your code should only know about the classes it is directly dealing with and should not be overreaching into classes that those classes know. As with all design principles this is quite intellectual and is difficult to translate to the code we write day to day. Personally I try and find concrete patterns for these that I can use to check if I am either infringing or obeying the principle. The Law of Demeter has a pretty easy check if you are disobeying it:

If you see a chain of calls (several dots) on a single line you are most likely violating the Law of Demeter

A concrete example of this is something like

boolean isGmailAccount = account.getProfile()

.getEmail()

.endsWith("gmail.com");

As you can see here our code has access to some Account class but this class also knows the internals of the Account class that is used to determine if it is a Gmail account. Checking against our rule you can easily see it violates the rule as there are 3 dots for chained calls and 2 of those are accessing different classes.

I want to make a quick note here that as per every rule there are exemptions. The key part of the above code is the call chain is accessing different underlying classes. This means that our code goes from only knowing about the Account class to now also knowing about the Profile and Email class. Said differently it means that our code is now coupled to the Profile and Email class and even their implementation. An example where there is a call chain but no extended class access is easily seen when using combinators on Streams in Java

List<MovieTitle> movieTitles = movies.stream()

.filter(Objects::notNull)

.map(Movie::getTitle)

.collect(toList());

Example

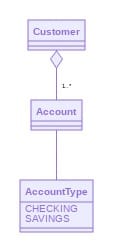

I am going to do a quick example where we work for a bank and we want to send an email to a customer about our new deal if that customer has a checking account with the bank.

This diagram is intentionally limited to not distract from the key elements.

These class all seem like we can represent these as plain data objects, they contain some values and we just create a whole bunch of getters. This was exactly my typical approach as I thought "I don't need my data classes to be very smart". So then to implement our requirement above we may need to write some code like this:

public void sendPromoEmail(Customer customer) {

boolean shouldSendPromoEmail = customer.getAccounts()

.stream()

.filter(x -> x.getType() == AccountType.CHECKING)

.findFirst()

.isPresent();

if (shouldSendPromoEmail) {

// Build promo message ...

emailService.sendEmail(customer.getEmail(), promoMessage);

}

}

This definitely does seem to do the job and we meet the requirements but if you look carefully this function doesn't quite satisfy the Law of Demeter. This function only knows about (or is coupled with) the Customer class. However because we choose to model our data with simple getters we need our function to know what is inside a Customer. This function is now coupled with how the Customer models the Accounts it has and is also coupled with the representation of the AccountType of Account. This coupling is quite subtle and will typically go unnoticed, I am not even needing to import the Account class for this to work!

The root of the problem here is that we chose to use dumb data classes that simply store data. I am not saying these don't work in all cases but I would urge you to consider if by doing so you end up in the same situation we are in here.

To remove this unneeded coupling we will need the data classes to now tell us more about themselves rather than us ask about it.

First thing we could do is change the Account class to tell us if it is a checking account.

class Account {

private final AccountType type;

// ...

public boolean isCheckingAccount() {

return type == AccountType.CHECKING;

}

}

Then our function becomes:

public void sendPromoEmail(Customer customer) {

boolean shouldSendPromoEmail = customer.getAccounts()

.stream()

.filter(Account::isCheckingAccount)

.findFirst()

.isPresent();

if (shouldSendPromoEmail) {

// Build promo message ...

emailService.sendEmail(customer.getEmail(), promoMessage);

}

}

Trust me I know this looks odd and what about all the other account types, does that mean we need to expand the Account interface for all of this? We may, but only if we ever use them of course. This encapsulation is a trade off as everything is. By creating this method the AccountType can be encapsulated withing the Account class, which means if we were ever change the representation or interface it would now only be the Account class we need to update. We don't need to go back to our sendPromoEmail function or any others that may be doing the same!

We have now removed the coupling with the AccountType and the next to remove is the Account. To do this we will follow the same pattern but one up the chain. We now want the Customer class to tell us if it has a checking account rather than us ask for its internals.

class Customer {

private final List<Account> accounts;

// ...

public boolean hasCheckingAccount() {

return accounts.stream()

.filter(Account::isCheckingAccount)

.findFirst()

.isPresent();

}

}

Then our function becomes:

public void sendPromoEmail(Customer customer) {

boolean shouldSendPromoEmail = customer.hasCheckingAccount();

if (shouldSendPromoEmail) {

// Build promo message ...

emailService.sendEmail(customer.getEmail(), promoMessage);

}

}

There we have it, we have removed the Account coupling in our function and it only knows about the Customer class and its interface. Now any changes to the Account class never reach this method and can ideally all be handled in the Customer class.

Posted on June 28, 2020

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.