Asynchronous Javascript - 04 - Promises

Kabir Nazir

Posted on February 29, 2020

In this article, we’re going to be looking at an interesting feature of Javascript that was introduced in ES6 in order to run asynchronous code efficiently. Prior to ES6, for running asynchronous code (for e.g. a network request), we used callback functions. But that approach had a lot of drawbacks (including callback hell) which gave rise to issues in code-readability, error handling and debugging. In order to overcome these issues, a new Javascript object called Promise was introduced.

Promise

A Promise is a special type of Javascript object which acts as a placeholder for the eventual completion or failure of an asynchronous operation. It allows you to attach 'handlers' to it, which process the success value or failure reason when they arrive at a later stage. This lets us call asynchronous functions as if they were synchronous and store them in a proxy object, which 'promises' to return the output at a later stage of time. Let us try to understand this better with an example.

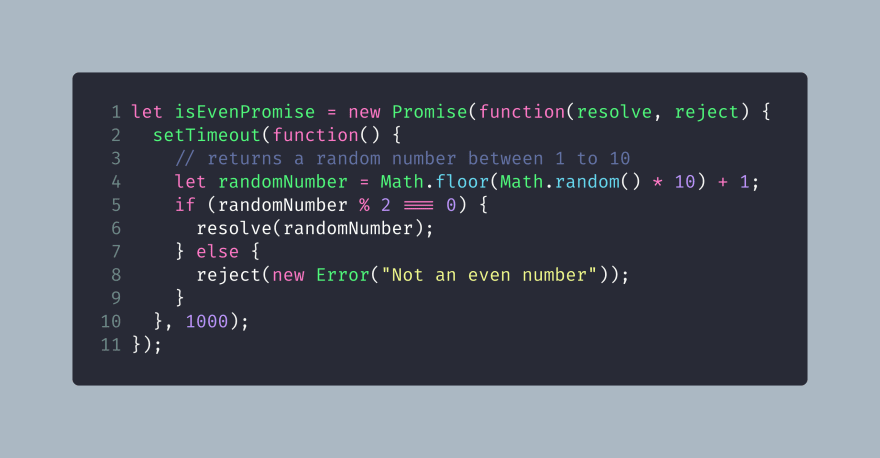

The basic syntax of a Promise is given above. A Promise is created with a function that is passed into it, called the executor function. The executor function contains the asynchronous code you wish to run. The function contains two parameters, resolve and reject. These are default callback functions provided by Javascript. The executor function is run as soon as a promise is created. Whenever the code of this function has completed running, we need to call either of the callback functions:

resolve(value): Calling this function indicates a success condition, with ‘value’ being the value returned from the successful completion of the executor function

reject(error): Calling this function indicates a failure or error condition, with the ‘error’ value being an Error object indicating the error details. ‘error’ doesn’t necessarily have to be an Error object but it is highly recommended.

The promise object returned by the constructor also has a few internal properties:

state: Set to “pending” initially. Changes to either “fulfilled” if

resolveis called or “rejected” ifrejectis called.result: Set to undefined initially. Changes to ‘value’ if

resolve(value)is called, or ‘error’ ifreject(error)is called.

Let us see how the above features work with a simple example.

The above code creates a promise to generate a random number from 1 to 10 and check if it’s even. We have used setTimeout in order to implement a delay of 1 second. When the promise object is created, its internal properties are set to their default values.

state: "pending"

result: undefined

Let us assume that the randomNumber generated at line 2 is an even number like 4. In this case, the code at line 5 gets executed and the resolve callback function is called with the value of 4 as its argument. This moves the promise object to a “fulfilled” state. This is analogous to saying that the executor function’s task has returned a ‘success’ result. The promise object’s properties now are

state: "fulfilled"

result: 4

If the randomNumber generated had been an odd number like 7, then the code at line 7 gets executed and the reject callback function is called with the Error object as its argument. This moves the promise object to a “rejected” state. The promise object’s properties now are

state: "rejected"

result: Error("Not an even number");

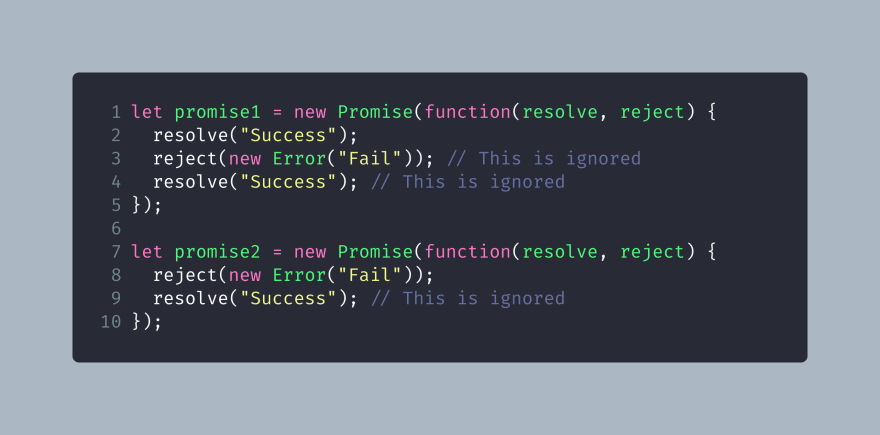

Note that in a promise, the executor function can call only either resolve or reject once. Any subsequent calls to either resolve or reject after the first one are ignored. This is because a promise is supposed to have a single result of either success or failure. Moreover, both resolve and reject accept only a single (or zero) argument. Additional arguments are ignored.

An important thing to note is that when a promise object is created, it doesn't immediately store the output of the asynchronous operation. The output (which might be either the success value passed by the resolve function, or the error value passed by the reject function) is obtained only at a later time. This output is stored in 'result', which is an internal property of a Promise and cannot be accessed directly. In order to obtain the result, we attach special handler functions to the promise, which we shall discuss below.

then, catch and finally

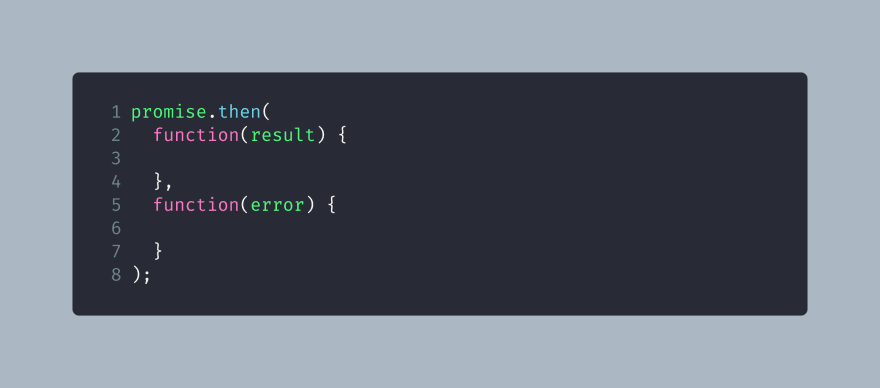

Promises have three important functions, or ‘handlers’ that can be attached to them, that allow us to receive or ‘consume’ their outputs. The first one is the then handler. The basic syntax of then is as follows.

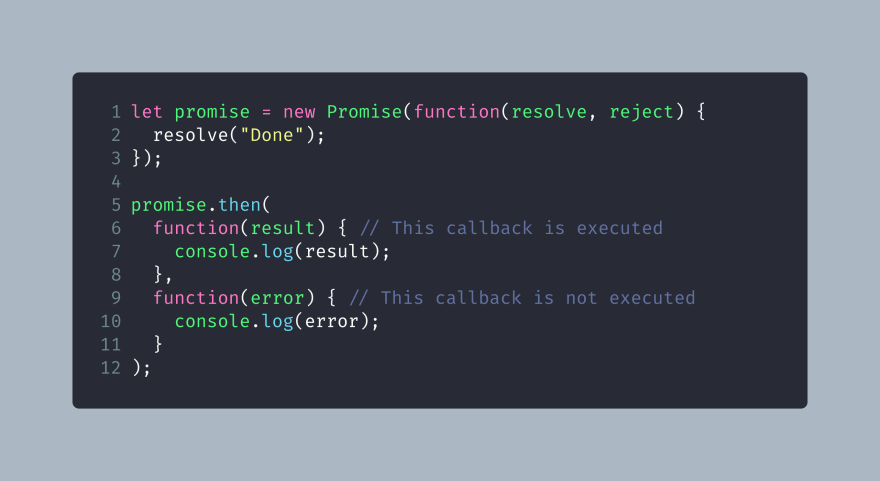

The then handler takes up to two callback functions as arguments. The first callback is executed if resolve was called in the executor function. The second callback is executed if reject was called in the executor function. For example, in the following promise, the resolve function was called in the executor function.

Hence, only the first callback was executed and the second one was ignored.

In the case of reject function being called,

The first callback was ignored and the second callback function was executed.

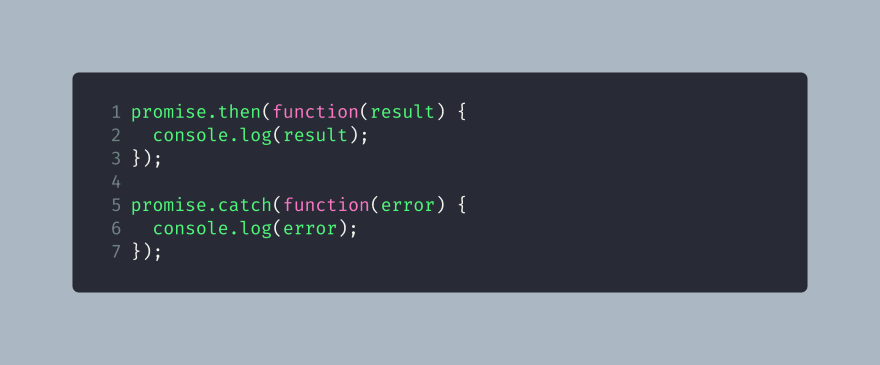

We can also have separate handlers to consume the results of resolve and reject. This is where the catch handler comes into play. It takes only a single callback function as an argument and executes it if the promise was rejected.

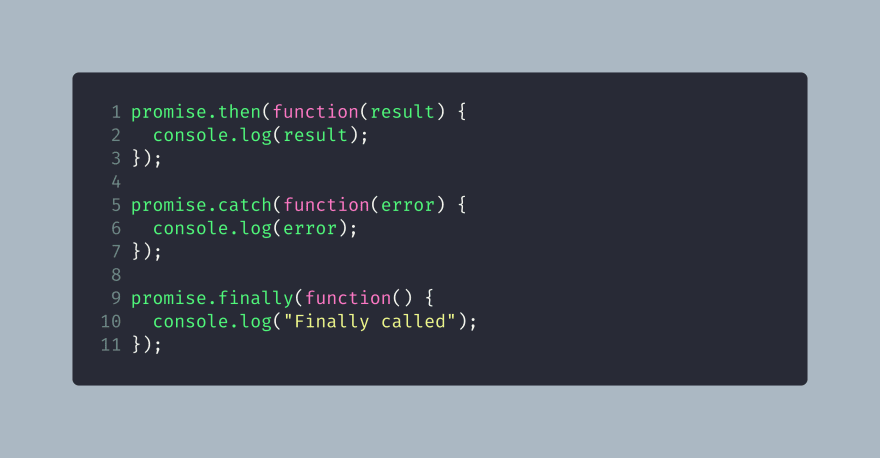

The third handler available is finally. This works similar to how final works in the normal try-catch scenario. The finally handler takes no arguments and is always executed if it is attached to a promise, irrespective of whether the promise was resolved or rejected.

We had mentioned earlier in this article about how one of the reasons promises was introduced was to overcome callback hell. The feature of promises that achieves this is the ability of chaining. The handlers of a promise, namely the then, catch and finally, all return back a promise. Hence, we can use these handlers in order to ‘chain’ multiple promises. Let’s look at a simple example.

In the above example, we have created a simple promise that resolves with a value of 10. Next, we consume this result with our first then function at line 5. This function prints the value ‘10’ into the console and then returns the value 10 * 2 = 20. Due to this, the promise returned by this then function gets resolved with a value of 20. Hence, in line 9, when the then function is being called, its result is 20. That result of 20 gets printed onto the console, followed by a return of 20 + 5 = 25. Again, the promise returned by the current then function is hence resolved with the value of 25. By repeating this, we can chain any number of promises to an existing promise. For more information regarding chaining, you can look up this document on MDN.

Now that we have looked at promises, you might be wondering where they fit into the execution order. Do promises’ handlers (then, catch and finally) go into the callback queue since they are asynchronous? The answer is no.

They actually get added to something called the microtask queue. This queue was added in ES6 specifically for the handling of Promises (and a few other types of asynchronous functions, like await). So, whenever a promise is ready (i.e. it’s executor function has completed running), then all the then, catch and finally handlers of the promise are added to the microtask queue.

The functions in the microtask queue are also given higher preference than the callback queue. This means that whenever the event loop is triggered, once the program has reached the last line, the event loop first checks if the microtask queue is empty or not. If it’s not empty, then it adds all the functions from the microtask queue into the call stack first before moving on to check the callback queue.

For more information on Promises, you could look up this document on MDN.

This concludes my series on Asynchronous Javascript. Feel free to leave a comment for any queries or suggestions!

This post was originally published here on Medium.

Posted on February 29, 2020

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.