Why You Need A Microservice Catalog

John Laban

Posted on April 28, 2020

John Laban is a co-founder of OpsLevel and previously was PagerDuty's first engineer. He's spent the last decade scaling engineering teams and helping them transition to DevOps. This article was first written on OpsLevel's blog.

Microservices are great. They help you grow and scale your engineering organization by providing better isolation and independence to your engineering teams. But they come with a sinister cost: a sharp increase in complexity.

Even with your very first microservice, you're already increasing your complexity by moving towards this distributed style of architecture. What used to be a method call is now a remote procedure call. You start having to really care about transactions, idempotency, retrying, backoff, etc.

But microservices don't just add technical complexity; they also add organizational complexity. As you add more and more microservices to the pile, you'll find that you'll get to the point where you've caused an entirely new organizational scaling issue.

After interviewing well over a hundred folks in companies with microservices architectures ranging from a small handful of services to many thousands, we've noticed a pattern: the inevitable sprawl and chaos of a microservice architecture starts to become noticeable at around 30-50 microservices.

In this article we'll cover the (very real) impact that this microservice sprawl has on companies, as well as the various solutions they typically go through to try and wrangle their microservices architecture: from spreadsheets, to wikis, to custom in-house-built software called Microservice Catalogs.

What is a Microservice Catalog?

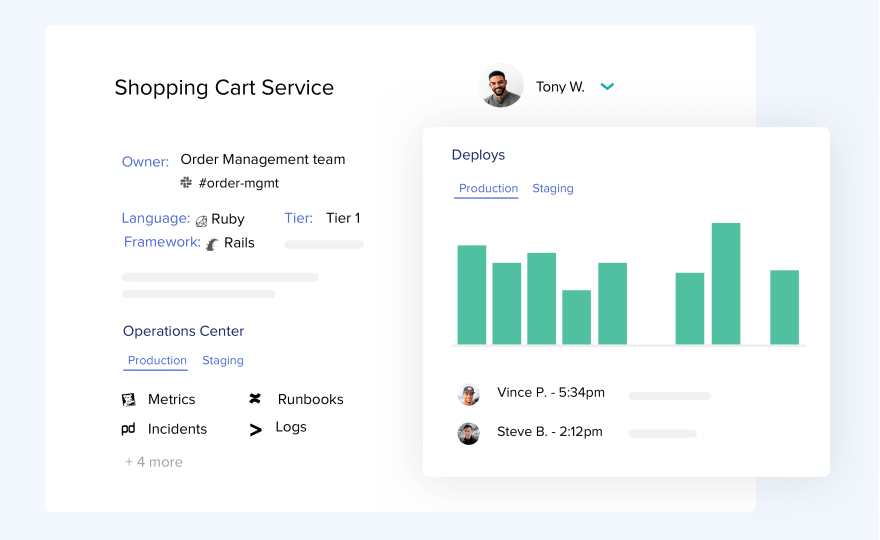

An example of a detail page from a Microservice Catalog

An example of a detail page from a Microservice Catalog

In essence, a microservice catalog tracks all the services and systems you have running in your software architecture in production. It tells you what each service does, who owns it, and how to operate it.

The info stored in a microservice catalog helps your team resolve production incidents faster, and you can use your catalog to build reliable and more operable microservices from the start.

Without a working microservice catalog solution in place, a lot of organizational challenges can come up.

Let's talk about the types of problems we see happening.

The Challenges of Having Lots of Microservices

After interviewing dozens of companies and hundreds of stakeholders within them, we've gathered a collection of problems that companies face when dealing with a lot of microservices.

Here are the most common ones we found:

1. There are too many services to keep in your head

Uber's microservice architecture (from SREcon19)

Uber's microservice architecture (from SREcon19)

Have you ever worked at a company that had that one person that knew every single service and system deployed in production?

To an engineering manager, they'd do anything to have this person on the team. To an engineer on the team, they would have an incredible resource that they could rely on for service information - information that is hugely helpful when debugging operational issues, or even when trying to avoid re-inventing the wheel with duplicate functionality.

And of course the Support and Product teams would love this person, too: they can be the universal router for service ownership.

Unfortunately, this person is very rare to come by. After you have about 50 services at your company, this person likely doesn't even exist!

After that point, it's simply too difficult - impossible even - for one person to keep track of all the details of all the microservices running in production. A microservice catalog makes this possible: it's basically service discovery, but for humans

2. The burden of service ownership is high

It can be very stressful going on-call for a service you don't know very well. When people join or leave your team, or when service ownership passes between teams, it can result in a lot of tribal knowledge getting lost. For some teams, it can even be difficult keeping track of the full set of systems they're responsible for!

Sometimes, people don't even know where to start looking to fix the problems with the microservices they own. "Where do I find the logs for this service? Are they in Sumologic, or still in our ELK stack? What index should I look under? I remember someone mentioning a runbook for this service; where do I find it? Is the health dashboard in DataDog or Grafana? Did a deployment or change go out recently for this service?"

Microservice Catalogs solve this problem by consolidating everything your on-call engineer needs to know in one place.

3. There are too many different technologies being used

As a company evolve, the different technologies used within it grows as well. One team might use a programming language that best suits their needs, while another might choose a different language or a different set of frameworks. If these decisions happen organically, a company can find itself with a ton of competing technologies being used at once on different teams.

This can work just fine for a while; if the team who created the service stays the owner, things stay happy and stable. But what happens during an inevitable company reorganization? Members of a single team might find themselves having to know upwards of 5 or more programming languages just to do their jobs. (I've seen it happen!)

Even a single technology can have a lot of different flavours. Ever work at a company using a bunch of different versions of Scala or Rails at once? Some of these can be significantly different from each other.

Developers finding themselves having to deal with all these different technologies cross-functionally might find the cognitive load way too high to be effective. And many of the technologies never reach enough of a critical mass of adoption within the company to get much high-leverage support from centralized infrastructure teams either.

Having a microservice catalog in place helps keep track of the different technologies and library versions used at a company. And once you can measure where you stand, it makes it much easier to drive campaigns to move towards adoption of a standardized set of technologies.

4. Implementing new technologies is a monumental task

If you've lived through a migration to Kubernetes, or a switch to a new cloud provider, or even through something as innocuous as a Java version upgrade, you know how hard it can be to roll out new technical initiatives across an entire engineering team. When engineering leadership decides it's time to implement new technologies, they are often faced with the challenge of effectively getting all their systems in line.

Just getting visibility into the situation can be a nightmare. I've seen situations where a group of engineering leaders would fire up a bunch of spreadsheets and start manually gathering information on technologies in production from each of their teams across the whole company. They'd meet every week with updated spreadsheets, checking off systems that have been migrated as they go.

But of course, this process was very painful for everyone involved: both for the engineering leads gathering the information and their teams giving them the information. And, of course, after the migration to kubernetes / vulnerability scanning / Java12 / etc is done, an exhausted engineering director / CISO / etc will throw away the spreadsheet. There's often nothing in place to make sure that new systems are following the golden path too.

Instead of this mess of spreadsheets and missed information, it's much easier to be continuously measuring everything with a microservice catalog as you go. Everything gets a lot easier when everyone has clear visibility into all the technologies, tools, and versions used at a company.

5. Security vulnerabilities aren't being fixed quickly

It goes without saying that reacting fast to the discovery of a vulnerability is very important. If your Security team discovers a vulnerability running in production, it's imperative they are able to find the team responsible for that service or system ASAP so they can update it. This can even be a requirement for compliance with SOC2 or PCI.

Again, microservice catalogs streamlines this process for all parties involved. They make sure that all services have an owner. It's simply a matter of finding the right service, looking up the team of people behind it, and then doing what needs to be done to patch up the vulnerability.

What are companies doing today to solve these problems?

When companies find themselves facing one or more of the above problems, they'll decide they need to start tracking all of their microservices in a centralized way. How do they do it? From an extensive set of calls with engineering leaders across a large number of companies, we've seen that they'll start with one of these three approaches (and usually all three, in order):

- Using spreadsheets

- Using a wiki page

- Building a microservice catalog in-house

The Spreadsheet Approach

Most companies start off with a spreadsheet, or more often, multiple spreadsheets. They'll be created by people with a specific problem they're trying to solve: figuring out how to get all services moved over to Kubernetes, or on vulnerability scanning, etc. This person will go and talk to every single team they can to try and get a full listing of the scope of the problem: i.e. the full list of services they need to get upgraded along with the team responsible for getting it done.

Using spreadsheets can work when getting started with your microservice catalog, but there are downsides to this approach:

- Creating spreadsheets require a lot of manual work

- There is often only one person updating the spreadsheet

- Giving everyone else access to edit (or even see) the spreadsheet can be difficult

- The spreadsheet gets out of date fast (usually when its owner moves on to a different project)

The Wiki Approach

Another common early approach is a wiki page. A wiki page "fixes" the accessibility and visibility issue, to some degree, as everyone in your organization should be able to edit and see the page. But it comes with its own downsides:

- The page gets unwieldy and large quickly

- Wiki pages are notorious for being left to rot

- It's difficult to gain insights from a big mess of unstructured data

The In-House Approach

When companies approach the ~50 microservice mark, using spreadsheets or wiki pages to catalog everything becomes very messy. After the tipping point of ~200 microservices, companies often find themselves building a microservice catalog in-house.

When it comes time to build their own in-house microservice catalog, they'll actually dedicate one or more engineers - sometimes a whole team - to build a system to catalog and store metadata on all of their microservices. Sometimes they'll add a subset of extra features - tracking their operational toolchain, tracking deploys, integrations into Slack or their git forge, metrics dashboards, tracking library versions, monitoring with operational checks & checklists, an API to integrate with other internal systems, tags for storing arbitrary service metadata, etc. Depending on how in-depth they go, building these internal catalogs can easily take a team the better part of a year. And they'll often need to dedicate time to maintaining and adding to it every year afterwards. This can get very expensive!

We've seen companies build these in-house microservice catalogs over and over again. Most top technology companies - after they get to a certain size - will have built one already. (Many have even deprecated it and built a v2 or v3 as well!)

OpsLevel is solving this problem for organizations

That's where we come in. OpsLevel was built to solve these organizational problems.

When I see a ton of tech companies repeatedly building the same in-house tooling, I know there's an interesting problem to be tackled. I first experienced this at PagerDuty when I joined as their first hire. The founders of PagerDuty and I had previously worked at Amazon together in the mid-2000's, and we saw how Amazon had built their own internal tool to page people when their services broke (informally called the "Pager Duty Tool" at Amazon.) Google and other tech giants had also built essentially the same internal tool to solve that same pain point. The founders at PagerDuty decided to go and solve the problem for the rest of the tech community. The domain name was still free, and so PagerDuty was born.

Similarly, I now see big tech companies - like LinkedIn, Spotify, Square, Atlassian, Shopify, and plenty more - all organically building essentially the same internal Microservice Catalog again and again, and spending a ton of time, money, and opportunity cost doing it.

But for those who haven't yet built one: why spend one of your most precious resources - your engineers' time - on something outside of your main line of business?

If you want to see how OpsLevel can help you grow your microservice architecture without the chaos, give us a shout.

Posted on April 28, 2020

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.

![Leadership is Everyone’s Responsibility [Testμ 2023]](https://media2.dev.to/dynamic/image/width=1000,height=420,fit=cover,gravity=auto,format=auto/https%3A%2F%2Fdev-to-uploads.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fuploads%2Farticles%2Fld22dgtfg0d0l2f8zmpp.png)