Distributed architecture: how to make microservices talk to each others?

Grégoire Mielle

Posted on August 31, 2020

Software engineers all aim for the same thing: creating a fault tolerant application to serve users's needs.

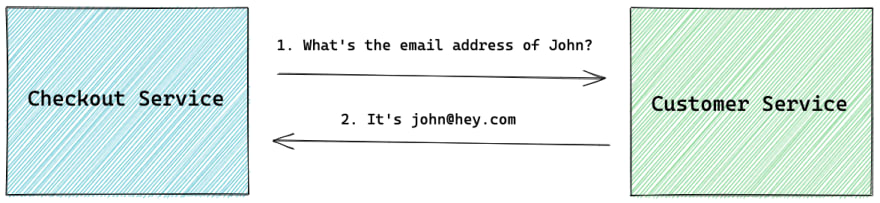

As an application and its services grow, so does the organization. Wether a microservice-oriented architecture was built from the ground up or you inherited a monolithic application turned distributed, the need for effective communication between services is clear: we want the checkout service to be able to talk to the customer service in order to send the order confirmation email to the right person.

Let's discuss what are the implications of putting a layer (the network) between services, the pitfalls we want to avoid & the best practises to maintain a fault tolerant experience for our users.

From a function call to multiple network requests: welcome to the the distributed paradigm world

While calling a service to send an email may seem trivial within a monolith, it can become a real headache with a distributed architecture. Indeed, within a monolithic application, calling a service can be summed up to an in-process function call, which is incredibly fast and (almost) always succeeds. Remote calls, on the other hand, can fail due to a failure in the remote process or the connection, thus potentially causing increased errors and latency.

When adopting a distributed architecture, we want to keep the same level of resiliency and performance while benefiting from its pros (independent teams, better testability & deployability, technical decoupling). So how do we make services talk to each other effectively?

The distributed monolith paradigm and how to avoid it

When migrating from a monolith to a distributed architecture (microservices-oriented) or when adopting a distributed architecture from scratch, it's easy to fall into the distributed monolith paradigm.

While microservices allow easy disposal of modules, they require careful consideration of cross-cutting protocols.

Because you want to be able to create new services in seconds while following DRY principles, you tend to think that most of the core pieces of a service should be shared across them: routing, tracing, etc. Also called platform libraries/packages depending on the organization you work in, they are the de facto dependencies you need to install to get started.

Now, what happens if you want to bump the version of one of those shared binaries in a new service: do you have to update it in all other services? And how easy it is to create a new service using a different language from the one in which those libraries are written in?

A trace generated with a different version of the tracing package can not be used, causing monitoring issues

The all promise of microservices independent deployability and technical decoupling is now gone: you've got a distributed monolith.

A better approach and way to avoid that scenario is to define network protocols & data contracts, just like programming languages have interfaces as Ben Christensen puts it in his talk "Don't build a distributed monolith". Thus, teams can choose to use or reimplement independent librairies depending on their timeline & architectural decisions.

Putting this pitfall apart, let's now compare the different ways you can use data contracts and network protocols to easily make distributed services talk to each others.

Data contracts & Network protocols: where do we start?

There are lots of ways to make two entities communicate over a network. One simple way to put it down is to compare synchronous communication mechanisms against asynchronous communication mechanisms to understand where they each work best.

Synchronous communication

Synchronous communication is the most straightforward solution when trying to make services communicate: the client sends a request and waits for a response from the service to come back.

A synchronous request is considered blocking, the response is needed for the process to continue

Most technologies around synchronous communication are associated with HTTP, including examples like gRPC, REST or GraphQL.

REST: Everything is a resource

Using REST, services expose resources which are available on dedicated endpoints using different HTTP verbs depending on the action you want to perform. Information is transported using JSON which leads to serialisation & deserialisation of each request's body.

- HTTP 1.1

- JSON

- HTTP verbs

- Almost never fully adhere to all principles: too strict for most apps

- Serialisation & Deserialisation

- Request/Response

- TCP handshakes for each request

gRPC: Calling remote functions from

Using gRPC, services are defined using Protocol buffers. Other services can then generate clients in different languages to send & receive Protobuf messages which are strongly typed.

- HTTP 2

- Protobuf messages

- Interfaces & Structured messages

- Strongly typed messages

- Streaming

Synchronous communication is easy to grasp but can pose some limitations: while making a query to get a result is supposed to be fast and can fail, how de handle requests that need to perform an action (also known as a command)? What if the command takes a lot of time to complete? Do we want to wait indefinitely risking to create a congestion at the service level?

Asynchronous communication: events & messages at the center

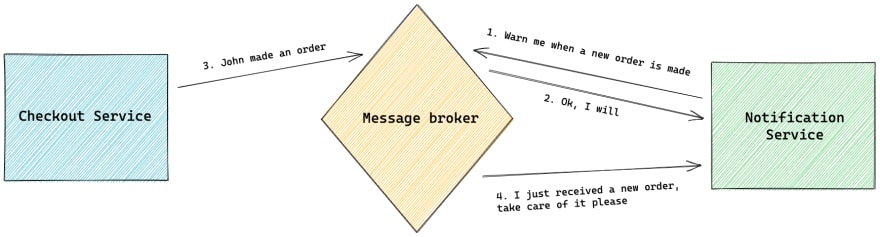

When a service performs a command that other services might be interested in (think of an order service on an e-commerce website), it can become really hard to keep track of all other services to call using synchronous communication. If one call fails, we don't want the whole order to be canceled.

This is when asynchronous communication comes into action. In an event-driven architecture, asynchronous communication between services is done using messages or events. A service produces an event (a record that something was performed) which can be consumed by other services that need to do their own work related to that change. This way, the service creating the event (the order service in our example) does not need to know which other services are gonna react to it, which leads to loose coupling between them.

If a service fails to consume an event, it's easy to re-send the event later or to a different instance of that service. With synchronous communication, we would need to handle this recovery mechanism in the service producing the event.

The service producing the message does not care which other services consume it

There are two asynchronous communication types:

Message queuing: One producer creates a message consumed by a consumer

Message queuing allows messages to be created by producers and consumed once by a consumer. Examples include RabbitMQ, NSQ or ActiveMQ.

Publish/Subscribe: Subscribers listen for messages added to a topic

The Publish/Subscribe pattern allows messages to be created by publishers in topics. Consumers subscribe to one or more topics and consume messages in that topic. Examples include Apache Kafka, Amazon SNS or Redis.

Synchronous vs asynchronous: when to choose one over the other?

Both types of communication have advantages and limitations. While event-driven architectures are hard to get right but offer loose coupling, synchronous communication is synonymous with high coupling but is simple to use & debug. It is very common to find both of them in the same application. Here are common rules you can apply to choose one over the other:

Use synchronous communication if:

- The operation is a simple query which is not changing any state

- The operation result is needed to move forward in the current process

- The operation can fail and does not require a complex retry mechanism

- The operation needs to be synchronous

Use asynchronous communication if:

- The operation involves multiple services reacting to it

- The operation is a command to change a state

- The operation must be performed while allowing failures & retries

The flaws you're exposed to when working with a distributed architecture and how to mitigate them

When putting a new layer (the network) between your microservices, your application is exposed to several pitfalls:

- Network latency: the time it takes for a request to get from one service to another increases, causing the application to be slow or unavailable

- Logical failure: a bug is introduced in a service which is key to your application, causing the application to be unavailable

- Congestion & scaling failure: the number of instances needed for a service to run properly is not enough, causing the application to be unavailable

When not handled properly, each of them can take a service down, which leads to increased latency & congestion for other services relying on it, thus making them saturated and more services to go down.

What is the main risk? A cascading failure leading to the whole application to be unavailable.

Software engineers should aim for two objectives:

- Failing fast & in silent: Services experiencing failures or anormal latency should be detected quickly and not create troubles for other services depending on it, thus limiting the blast of the issue.

- Fallback and gracefully recover: Services which depend on a failing service should be able to rely on an alternative solution while the impacted service is restored to its normal state.

Widely used solutions which meet those objectives follow the circuit breaker pattern. By acting like electrical circuit breakers, they can stop remote services from accessing a service which experiences a high rate of failures immediately. After a timeout period, traffic to that service can resume if no new errors are detected. While solutions dedicated to this task like Netflix's Hystrix, Resilience4j or Alibaba's Sentinel exist, service meshes like Istio also contain traffic management features to enable it.

Wrapping up

Distributed services communication is hard to get right from the ground up. When considering existing services interactions and scaling issues, it gets even harder. Here are some principles you can follow:

- Each service should define clear data contracts & communication protocols with other services

- Critical services need to be listed and circuit breakers need to be in place to ensure their resiliency to other services's failures

Even with the best architecture, your application is not protected from bugs introduced in new releases, worsened network connections or cloud systems failures. This is why monitoring tools and observability are even more important in a distributed context.

This story was originally published on Redefined.cloud, an open-source publication where to get started with cloud computing using simple words and analogies you can understand.

Posted on August 31, 2020

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.

Related

August 31, 2020