Introduction

Recently I have been doing a lot of work and study in machine learning, including DeepRacer, and part of that is finding a way to accelerate the required computation. A lot of frameworks and libraries will use CUDA however a couple like PlaidML use OpenCL. I am big advocate for open source software, preferably free but alas, so when frameworks and libraries only use CUDA for acceleration that really irks me. For those not in the know, NVIDIA (owner of CUDA) has a horrible history with open source communities and supporting implementations for the open source community (looking at the NVIDIA drivers for Linux). So I really want to get into OpenCL, and be part of the change I want to see, which is supporting a standard that is free and open to all.

When I started writing this piece I wanted to go into OpenCL and how to use it to implement recursion, but as I got into it I realised there is simply too much content. So in this Part 1 of many. In this piece I will be going into the basic approach of OpenCL with a sample and how that is broken apart in OpenCL calls. Onwards to the content!

Just quickly though, all the sample code can be found in my repository for these posts.

A accompanying repo for my writing about OpenCL

adventures-in-opencl

A accompanying repo for my writing about OpenCL - https://dev.to/crr0004/series/1481

Building

You will need a driver that implements OpenCL 2.0 and cmake.

This was compiled using clang. It should automatically pick up your primary

OpenCL vendor and use that.

Headers

The OpenCL headers are included in this repo under shared, if CMake doesn't find them, you can override the directory with "-DOPENCL_INCLUDE_DIRS=../../shared/" when building from one of the build directories. Change the path if it is different for you.

When running it will print out what device is being used but if your

vendor implementation is broken it can crash your driver.

Running

Run each sample from the source directory as it needs to pick up the kernel

files

Used libraries

See LICENSE file for addition of respective licenses

What is OpenCL

"OpenCL (Open Computing Language) is an open royalty-free standard for general purpose parallel programming across CPUs, GPUs and other processors, giving software developers portable and efficient access to the power of these heterogeneous processing platforms." (Khronos OpenCL 20 API Specification 2019 p. 11).

There have been multiple standards/libraries/frameworks/languages over the years that cater to parallel computing and they have various benefits and faults. Very few of those are on the hardware level, and even fewer are device agnostic, that is, they aren't programmed specifically for the device. This is where OpenCL really shines. It's implemented against a specification so you're not vendor locked (there is a caveat here for extensions and optimisation). It's royalty free so vendors don't pay for implementing it and communities can pop up around with little initial friction. If you want a parallel to draw (pun intended) then you can look at the adoption of OpenGL, Vulkan, OpenGL ES (phones use this a lot), WebGL, and basically any Khronos Group specifications.

Going forward I will mainly be talking about OpenCL 2.0, however I will try to note where parts are not present in OpenCL 1.2 as the specification directly mentions being backwards compatible (Khronos OpenCL 20 API Specification 2019 p. 57) and I will try to keep that going. That goes for all pieces I write on OpenCL.

Okay but how do we go fast?

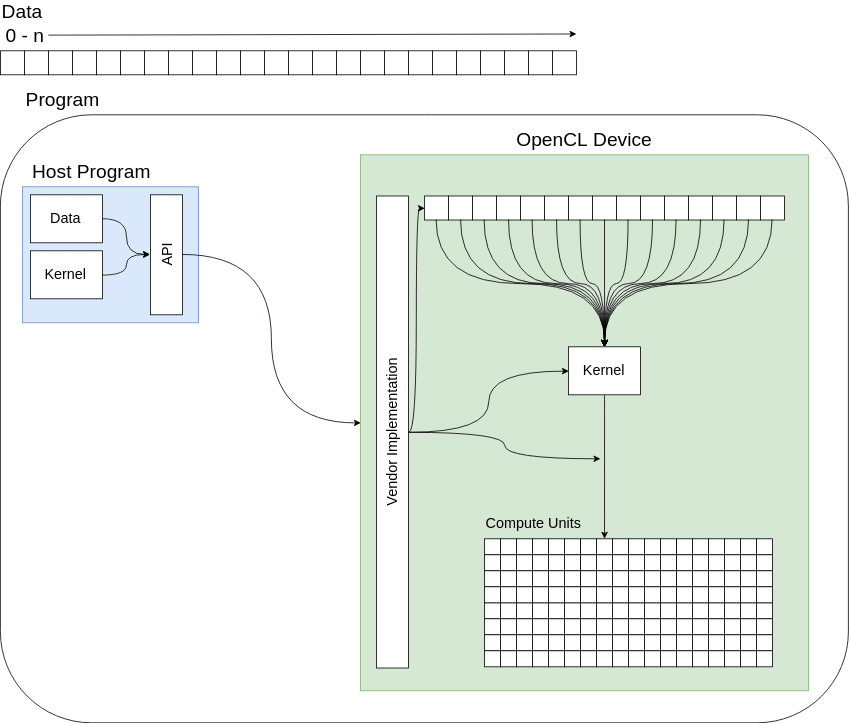

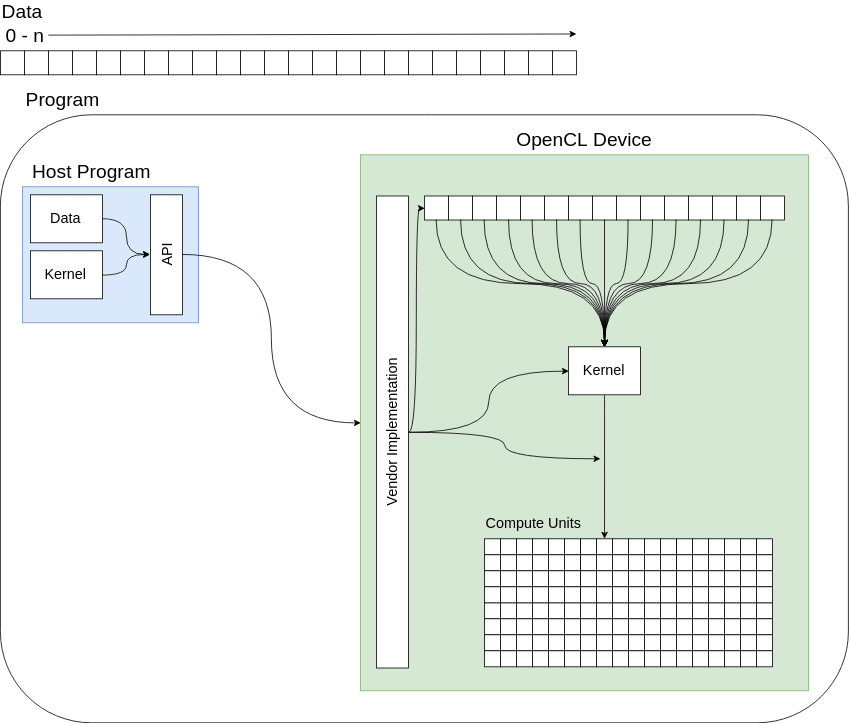

In case you're new to parallel computing (This is my first deep dive), the easiest way to think about it that I've found, is to ask "Given infinite amount of compute units and infinite memory, how do we use it all?", so hopefully that leads you to the realisation that what we need to do is write software that can take advantage of those resources. So to go fast we have to some way to get all those compute units to operate on our memory in some useful way. OpenCL gives us a lot of ways to do this, and one way is to simply directly map one section of memory to one compute unit. OpenCL does us a kindness and specifies how this works when we have more memory than compute units, it specifies "work groups" with "work items".

Work groups are made up of work items, and a device driver specifies how big a work group can get. So if we a list of numbers with 1024 integers and a device with 64 compute units, there would be 16 work groups (1024/64). The device does not have to complete all these work groups at the same time, it just has to eventually do it. The following diagrams shows a basic structure of this, without worrying about the breaking up of work items into groups.

To do the actual computation, you write a "kernel", compile it, and then hand it off to the device with the data you want to compute on. You can see the naive_approach sample in my repository to see how this actually done.

If you have an AMD or Intel device that supports it, you can even use a debugger from their SDKs. I know AMD's is CodeXL, and Intel has debuggers in their SDK. For NVIDIA cards, you can try their Nsight software however I am not entirely sure if it's reliable or not, and their is not linux version I can find

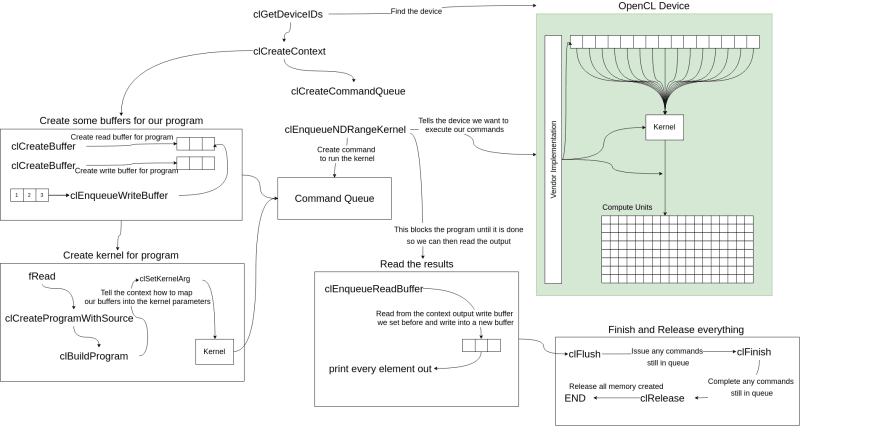

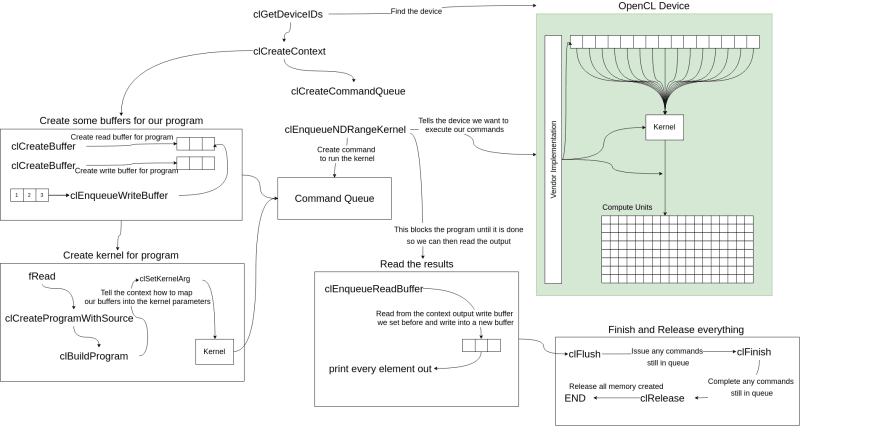

Sample In Diagram Form

The following diagram is a rough break down of the APIs that the sample uses. Don't feel like you have to completely understand the diagram because it is just trying to give you an idea how the various API calls map into an actual program.

You can find all the details of the OpenCL API calls in the OpenCL API Reference pages.

TL;DR

OpenCL is another standard from the Khronos Group that enables device agnostic approach to parallel computing. There are various ways to do this and the first approach you should take is taking a list of numbers, your compute kernel, and then give it to the device to do. The devices can do fancy stuff to make this work properly, more detail to come in future posts!

References