Demystifying JavaScript Closures

Ashwanth A R

Posted on September 27, 2020

For a long time, I've perceived closures as this arcane topic that had a tendency to unnerve me. However, it is a powerful feature of JavaScript that lets you do some neat stuff. In this article, I will cover its basics and we will look at one practical usage, and hopefully you will find it intelligible as well (if you don't already).

The core of JavaScript

JavaScript is a single-threaded language. This means that it can only run/execute one piece of code at a time and must finish it, before executing the next bit. In layman's terms, it cannot multi-task. In more technical terms, it has,

- One Thread of Execution

- One Memory Heap

- One Call Stack

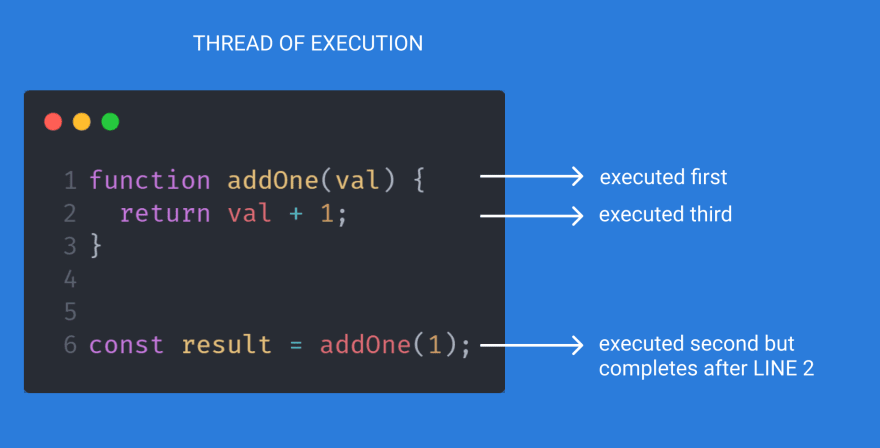

The thread of execution basically refers to JavaScript's thread, going line by line over your code and executing each line. There is a caveat to this however. If a function is encountered, JavaScript will declare the function in memory and move to the next line after the function. It will not go into the body of the function until a function call is encountered. Once the function completes, it will then jump back (return) to the line that initially called the function.

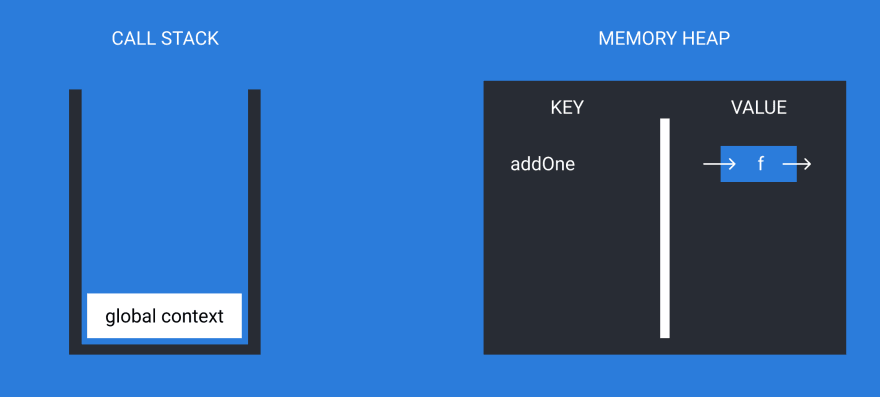

Before your code starts to run, a global execution context is created with a memory heap. An execution context is the environment in which your thread of execution runs.

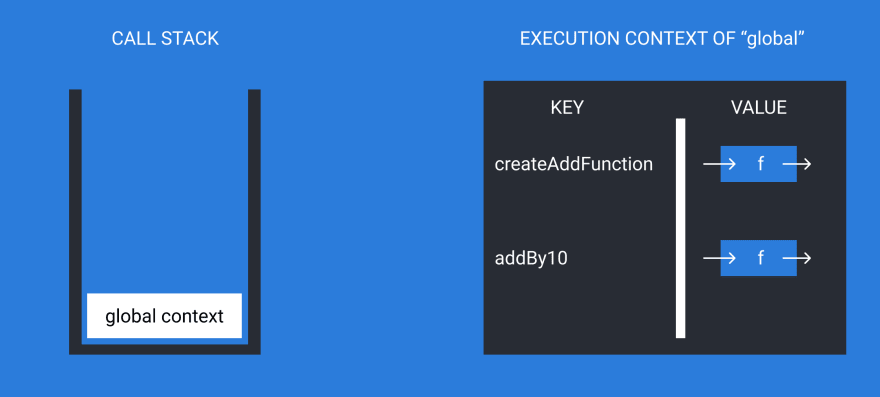

Every time your thread of execution enters an execution context, this context is pushed onto your call stack. Therefore when your code starts to run initially, global context is pushed onto the call stack and the JavaScript compiler encounters LINE 1.

It takes the entire function definition (along with the code) and stores it in the memory heap. It does not run any of the code inside the function.

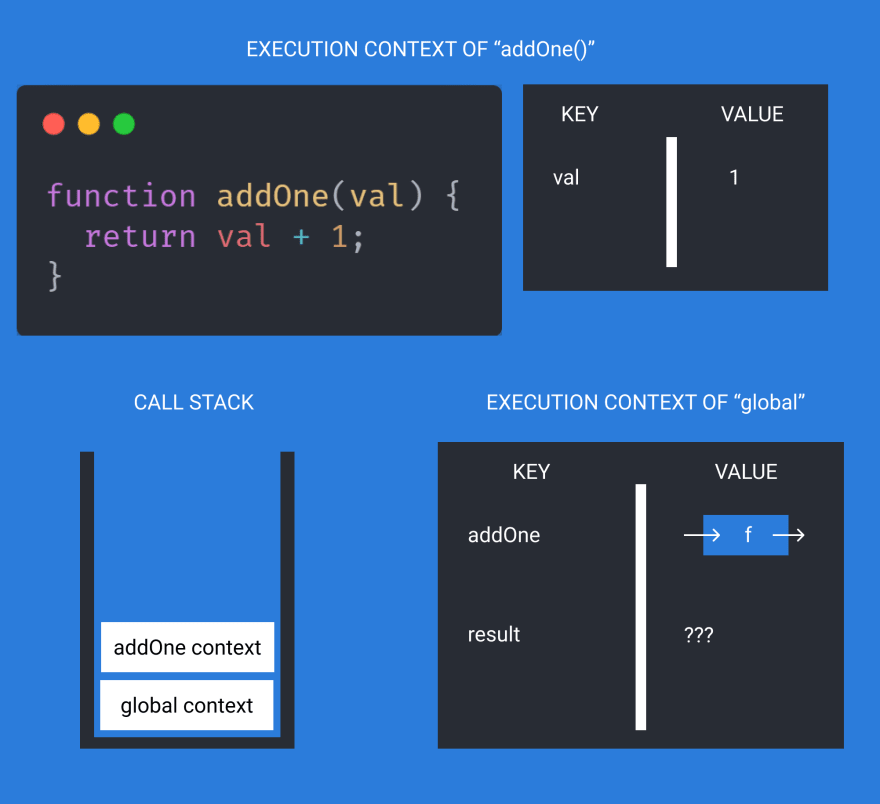

The next line in the order of execution is LINE 6, where the function is called (or invoked). When a function is called, a new execution context is created and pushed onto the stack. It is at this point, that JavaScript enters inside the function to execute the function body (LINE 2).

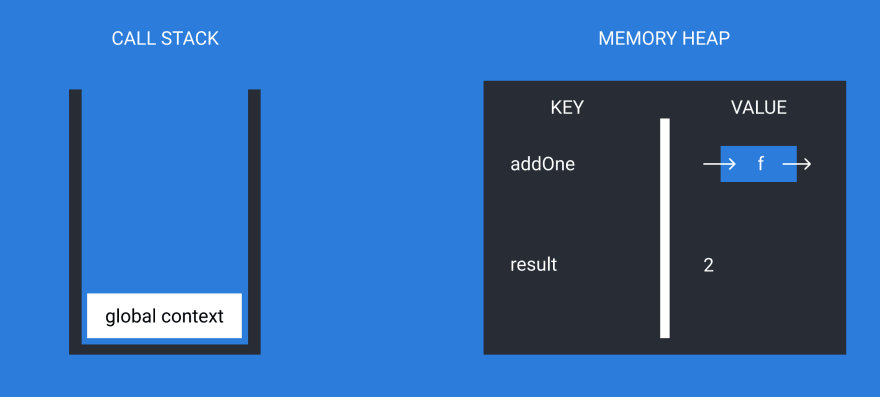

It is also interesting to note that LINE 6 has not completed its execution though (result is still uninitialized), it is now waiting for the function to complete its execution at which point the addOne() context is popped off the stack and destroyed. Before destruction however, it will return the calculated value back to LINE 6 and initialize the value of result.

Where do closures come into the picture?

Now, I mentioned in the previous paragraph that the execution context of addOne() is destroyed after the function has completed its execution. So there is no label called "val" in our memory with a value initialized to it anymore. Its all been completely removed from memory.

This behavior is a good thing, because each time we run our function with different arguments, we don't typically need to know what values the function was previously run with or what intermediate values were generated during execution. But, there are some cases where having memory attached to our function definition that persists across execution will prove to be a powerful capability that lets us do incredible things.

Attaching memory to function

Let's look at some code,

function createAddFunction(n) {

function addByN(val) {

return val + n;

}

return addByN;

}

const addBy10 = createAddFunction(10);

console.log(addBy10(2));

Here we have a function, createAddFunction which takes a parameter n and returns a function called addByN. Let's break this down. When the compiler starts, it creates a global context, and encounters LINE 1 where it defines a label in memory (called createAddFunction) and stores the entire function definition under this label.

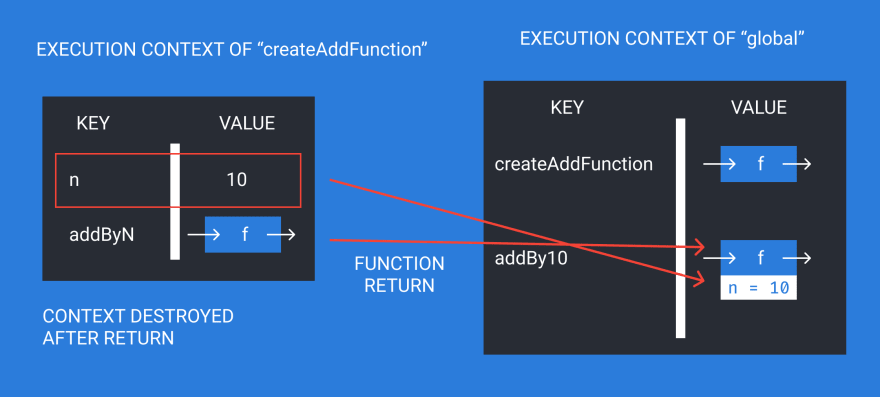

Next, it creates a label in memory called addBy10 which remains uninitialized till the function call createAddFunction() finishes execution and returns. When this function gets executed, it creates a new execution context and pushes this on to the stack. Since we pass the value n as 10, this gets stored in the createAddFunction context. In the function body, it also defines addByN function to be stored in memory.

Then it returns this function addByN to be stored as initial value for addBy10 label in memory. Once the value has been returned, the createAddFunction execution context is popped off the call stack and destroyed.

We then invoke the function addBy10(2) with an argument 2.

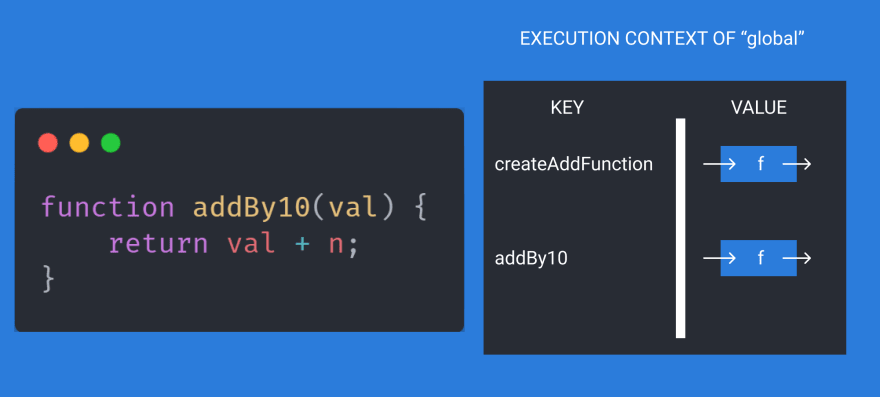

Our addBy10 function would be defined as above. Its the same as our addByN function except it is now stored under a different label in memory. Here comes the kicker. The parameter val takes on the value 2, but what is the value of n ? Its not defined inside our function, nor is it defined in our global execution context. Furthermore, there are no other execution contexts left because createAddFunction context was destroyed. At this point, we would expect n to be undefined, but its not. Thanks to how JavaScript behaves in these circumstances because of closures. Our function somehow remembers that the value of n at the time of function creation was 10 and thus we can say, our function has persistent memory.

Lexical Scoping and Closures

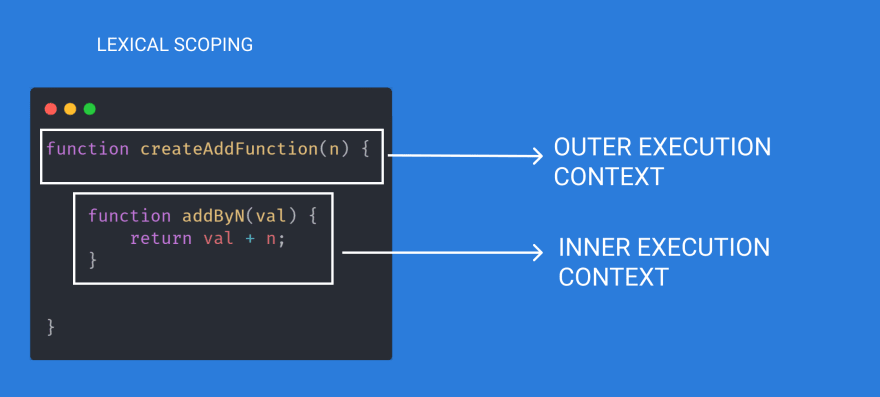

Scope is the set of rules in a programming language that dictates what data is available to the compiler within a particular execution context. JavaScript has the scope rule of Lexical / Static Scoping. Lexical Scoping is a description of how the JavaScript compiler resolves variables names when you have functions nested. That is, the parent of a function determines what data that function has access to (in addition to the data that is local to the function).

When the thread of execution is inside the inner execution context, it has access to variables defined in the outer execution context via our scoping rule.

So, when the addByN function is returned from the createAddFunction execution context, it takes along with it all the variables that it has access to. Because of lexical scoping, this includes the key-value pair of n and 10. This is called a closure. A closure is the combination of a function and the lexical environment within which that function was declared

So, our label addBy10 is not merely a reference to a function anymore, but a reference to a function and a data store (that persists before, during and after the function call).

It is important to note that this value of n = 10 cannot be accessed in any other way but by calling the function and this usage depends on how the function was originally defined. Hence, it is protected persistent data.

Iterators using closures

A good example for closures is iterators in JavaScript. An iterator is an object which defines a sequence of values that can be accessed by having a next() method which returns an object with two properties: value (next value in the sequence) and done (boolean to track whether sequence has already been iterated over).

If we try to implement a simple iterator, we can see the usage of closures.

const makeIterator = (arr) => {

let currentIndex = 0;

return {

next: () => {

if (currentIndex < arr.length) {

return {

value: arr[currentIndex++],

done: false,

};

}

return {

value: arr[currentIndex++],

done: true,

};

},

};

};

The makeIterator function creates/makes an iterator object and returns it. This can be used as follows:

const iterator = makeIterator([1, 2, 3]);

let result = iterator.next();

while (!result.done) {

console.log("RESULT", result.value);

result = iterator.next();

}

We had to use a closure in this case because we needed to store (in memory) and track the currentIndex across the next() function calls as we consume our iterator.

Some other places where closures are used are in the implementation of generators, promises etc. It can also be used in functions that perform large computations to store previous computations in order to not repeat it if the same arguments are passed in (memoization). Closures provide you a powerful toolkit to writing modular optimized code. And I hope with this explanation, you are as excited about using them to write better code as I am.

If you have any feedback, questions, clarifications, please drop a comment and I'm happy to engage in a discussion to improve the quality of my content. Thanks for reading.

Posted on September 27, 2020

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.

Related

November 14, 2024

November 10, 2024