Mykola

Posted on March 28, 2024

Hello there! It's been a while since I wrote here - all of a sudden, 2024 became way busier than I planned it to be. But hey, it's good to be back!

Similar to my previous post, Understanding CORS, this one has the same backstory: lately, I have had to explain a few times to different people about such concepts as JSON Web Tokens (JWT), their structure, types, use cases, etc., so I realized that it would be smart to write a post about that and use it for the future reference. I hope it will be helpful for someone else out there.

Traditionally, let's start with a real-life example.

Real-life example

Let me introduce you to Craig and Clyde, two buddies from the same class. They like to hang out together after school, but they also don't miss the opportunity to chat during the lessons. It didn't go unnoticed by their teacher, Mr. Garisson, so he made sure they didn't sit next to each other. Well, challenge accepted, there are other ways to contact each other: their classmates use smartphones and different message apps for that, but these two dudes are a bit nerdy, so they came up with something smarter - they pass messages written on a piece of paper. However, the message written on a piece of paper is not plain text but something more complicated. Let me show you a small example.

Imagine that Clyde wants to send a "Hello there!" message to Craig. Then, the message on a piece of paper will look like this:

ewogICJzdWIiOiJDcmFpZyIsCiAgImlhdCI6MTcxMDYxMTk1MywKICAibWVzc2FnZSI6IkhlbGxvIHRoZXJlISIKfQ

Weird, right? How come is the mumbo jumbo above "Hello world!"? And why bother? Too many characters for such a simple phrase! Good questions, my friend! There are 2 good reasons for the following:

- Remember, I mentioned that their teacher made sure that they didn't sit next to each other? Well, actually, there is only one desk between them, but the guy sitting on that desk, Eric, is well-known for his curiosity and evil pranks attitude. And since the piece of paper goes through him each time, Craig and Clyde had to come up with some layer of privacy. This leads us to the 2nd reason.

- As I stated while introducing the guys, they are nerdy, so they found it to be funny in their way.

Ok, the "why" is clear now, but the "how", or, to be more specific, the "what the hell is that text?" question remains. That's the exact question Eric asked himself each time he passed the piece of paper between Craig and Clyde as his curiosity grew day by day.

Soon, he understood that there was no way he could solve the mystery on his own, so he went to the place where other nerdy folks hang out - the internet! Some "good" people out there, after shaming him for asking such simple questions, gave him a hint that this piece of text is nothing more than a Base64URL-encoded string, and there are plenty of online tools to decode it.

Decoding the message

Once Eric posted the text he copied from the piece of paper to the Base64URL online decoder, he saw this output:

{

"sub": "Craig",

"iat": 1710611953,

"message": "Hello there!"

}

Lucky day, the mystery is not a mystery anymore!

If Eric had some coding experience, he could have easily decoded the text without any online tools by using this code:

func main() {

encodedMessage := "ewogICJzdWIiOiJDcmFpZyIsCiAgImlhdCI6MTcxMDYxMTk1MywKICAibWVzc2FnZSI6IkhlbGxvIHRoZXJlISIKfQ"

res, _ := base64.RawURLEncoding.DecodeString(encodedMessage)

fmt.Println(string(res))

}

All the code examples are available here. If you run this code, you'll see the same JSON printed to the terminal as above.

As you can see the original JSON contains several fields:

-

substays for "subject" and specifies whom the message refers to -

iatis the acronym for "issued at" and shows when the message was created in a Unix epoch seconds timestamp fashion - meaning how many seconds have passed since thebeginning of times1st January 1970 -

messageis self-explanatory and the main reason of all this hustle

Not sure about you, but for me all of these fields make sense, as they somewhat mimic the message and associated metadata we can see in WhatsApp/Telegram/Signal/SMS/youNameIt messaging apps.

If you don't know what Base64URL encoding is, let me give you a brief explanation: it is a technique for transforming any text (or binary data) into a sequence of characters. A set of 64 unique characters is used for the resulting text. It means that regardless of whether the input is Latin, Cyrillic, Arabic, Chinese, etc. chars, the output is always generated with the same 64 characters. That's where the "64" name part comes from. The important moment to highlight is that the text can be easily encoded and decoded back and forth by anyone, as Base64 doesn't imply any security for the original input. Check the corresponding Wikipedia page for more details about Base64 and its Base64URL subtype.

As you can see, I highlighted the

the text can be easily encoded and decoded back and forth by anyone, as Base64 doesn't imply any security for the original input

part. As soon as Eric learned this, he immediately saw the opportunity for a cool evil prank there.

The prank

The idea behind the prank was both simple and easy: since now Eric knows how they encode their messages, nothing stops him from decoding the original input, modifying the message field value in some evil way, decoding it back, writing to a piece of paper and passing it forward to the desired destination. Guys don't suspect he knows their secret, so he has an advantage.

Soon enough, he received a piece of paper from Craig that he was supposed to pass forward to Clyde. The text looked like that:

ewogICJzdWIiOiJDbHlkZSIsCiAgImlhdCI6MTcxMDYxNTMzOCwKICAibWVzc2FnZSI6IkxldCdzIHBsYXkgZm9vdGJhbGwgdG9nZXRoZXIgbGF0ZXIgdG9kYXkhIgp9

"An opportunity!" - Eric immediately decoded the message the way he already knew, and saw this:

{

"sub":"Clyde",

"iat":1710615338,

"message":"Let's play football together later today!"

}

"Let me fix this a bit!"

{

"sub":"Clyde",

"iat":1710615338,

"message":"I see that I'm too smart to be friends with a guy like you - don't talk to me, ok?"

}

But how to decode this back? Well, while there are plenty of online tools to help with that, let's achieve the same result with the code:

func main() {

message := `{

"sub":"Clyde",

"iat":1710615338,

"message":"I see that I'm too smart to be friends with a guy like you - don't talk to me, ok?"

}`

encodedMessage := base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString([]byte(message))

fmt.Println(encodedMessage)

}

The result is:

ewogICJzdWIiOiJDbHlkZSIsCiAgImlhdCI6MTcxMDYxNTMzOCwKICAibWVzc2FnZSI6Ikkgc2VlIHRoYXQgSSdtIHRvbyBzbWFydCB0byBiZSBmcmllbmRzIHdpdGggYSBndXkgbGlrZSB5b3UgLSBkb24ndCB0YWxrIHRvIG1lLCBvaz8iCn0

Eric quickly replaced the original text on a piece of paper with a new one and passed it to Clyde. Soon enough, he got Clyde's response which contained the message that if I decided to share here, I'd need to use a "Strong language" warning. "Great success!" - Eric thought and tried hard not to laugh. I told you about his attitude, so don't be surprised!

For the next couple of days, there was no correspondence between the two friends, so Eric felt kinda proud of his smart little trick. But one rainy day (like that wasn't too bad already), Craig gave him a piece of paper and asked to pass it to Clyde. Eric immediately realized that something was wrong with the message:

ewogICJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLAogICJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIKfQ.ewogICJzdWIiOiJDbHlkZSIsCiAgImlhdCI6MTcxMDYxNzA5MSwKICAibWVzc2FnZSI6IkhleSwgYnVkZHkhIEJvYXJkIGdhbWVzIHRvbmlnaHQhIgp9.ny29zDJjI-QCbihNyPx7hjj0wxpM3E6Isagktf9U-1o

When he tried to decode it via the online tool, he got this output:

{

"typ":"JWT",

"alg":"HS256"

}'7V"#$6ǖFR"&B#scs&W76vR#$W'VFG&&BvRvBFF EI?U6?=W(KtC

which was definitelly off. Trying the same with the Go code didn't change the result much:

{

"typ":"JWT",

"alg":"HS256"

After the short moments of panic, Eric calmed himself down and took a closer look at the new message format. Soon enough, he noticed an interesting moment: the message contains 3 parts that are separated by the . symbol. "Ok, we are getting to something!" It seemed logical to try to split the text into 3 chunks and decode them separately:

func main() {

encodedMessage := "ewogICJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLAogICJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIKfQ.ewogICJzdWIiOiJDbHlkZSIsCiAgImlhdCI6MTcxMDYxNzA5MSwKICAibWVzc2FnZSI6IkhleSwgYnVkZHkhIEJvYXJkIGdhbWVzIHRvbmlnaHQhIgp9.ny29zDJjI-QCbihNyPx7hjj0wxpM3E6Isagktf9U-1o"

chunks := strings.Split(encodedMessage, ".")

for _, chunk := range chunks {

res, _ := base64.RawURLEncoding.DecodeString(chunk)

fmt.Println(string(res) + "\n")

}

}

The result is:

{

"typ":"JWT",

"alg":"HS256"

}

{

"sub":"Clyde",

"iat":1710617091,

"message":"Hey, buddy! Board games tonight!"

}

�-��2c

"Ha! And they call themselves smart!". The first and the third parts looked kinda of weird to Eric, but was sure they tried to confuse him this way, so without further hesitation, he changed the message part of the second JSON to "Hey! Board games tonight for smart guys only, so you are not invited!", encoded it back, appended 1st and 3rd part to where they belong to unchanged and passed the modified piece of paper to Clyde. The answer came back in a few minutes:

ewogICJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLAogICJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIKfQ.ewogICJzdWIiOiJFcmljIiwKICAiaWF0IjoxNzEwNjE3MTkxLAogICJtZXNzYWdlIjoiTmljZSB0cnksIEVyaWMsIGJ1dCBnbyBwbGF5IHdpdGggdGhlIGtpZHMgaW5zdGVhZCB3aGlsZSBtZW4gYXJlIHRhbGtpbmcgaGVyZSEiCn0.m1HhjXosZYlEdiOHE8X_34ydYBBNAhG08xgZBigaXtE

Eric started decoding it with great impatience, being twice as proud of himself. However, the result was far from what he had expected:

{

"typ":"JWT",

"alg":"HS256"

}

{

"sub":"Eric",

"iat":1710617191,

"message":"Nice try, Eric, but go play with the kids instead while men are talking here!"

}

�Q�z,e�Dv#�

"What's going on?!!"

The anti-prank measures

Little did he know that Craig and Clyde talked to each other to resolve the conflict they thought they had and figured out they had been fooled. And that was easy to guess who did that. The harder part was to come up with an idea of how to prevent this from happening. They realized Eric could read their messages, but that was fine - they didn't share anything sensitive. But the ability to modify them wasn't something they had a piece with. It meant they needed a way to see whether the original input had been changed along the way. And nerdy folks like them (or you and I) know the answer - the signature!

If you are not familiar with this concept, no worries, it is pretty simple and looks like this:

- imagine there is a text that we'd like to make sure stays the same along the way

- we need depending on the algorithm, either a secret phrase that both sender and receiver know, or the private and public key - only the public key is shared with the receiver in this case

- the sender takes the original text and applies a specific signing algorithm on it with the usage of either the secret phrase or the private key - the result looks similar to the third part of the message we saw above: for example,

ny29zDJjI-QCbihNyPx7hjj0wxpM3E6Isagktf9U-1o- we'll call this a signature - the signature is passed alongside the original text all the way to the receiver

- once receiver gets a message:

- if the secret phrase was used, the receiver calculates the signature for the text they received the same way as the sender did above and compares the two - if they are the same, the original text was not modified; otherwise - it shouldn't be trusted. As long as the secret phrase is kept safe, the man-in-the-middle has no way to both change the text and add a valid signature to it

- if the private key was used, the flow is a bit complicated, and we'll discuss it a bit later, but the high-level idea remains the same

As you can already guess, that's exactly the measure that Craig and Clyde took against Eric's prank, and that's how they noticed when he replaced the original message with the fake one.

Let's see how they achieve that by code. The secret phrase part was easy as they agreed on it before the lesson, so they both knew it.

func main() {

// sender part:

secretPhase := "goToHellEric"

part1 := `{

"typ":"JWT",

"alg":"HS256"

}`

part2 := `{

"sub":"Eric",

"iat":1710617191,

"message":"Nice try, Eric, but go play with the kids instead while men are talking here!"

}`

part1Encoded := encode(part1)

part2Encoded := encode(part2)

signature := sign(part1Encoded, part2Encoded, secretPhase)

encodedMessageWithSignature := part1Encoded + "." + part2Encoded + "." + signature

fmt.Println(encodedMessageWithSignature)

// receiver part:

parts := strings.Split(encodedMessageWithSignature, ".")

receiverSignature := sign(parts[0], parts[1], secretPhase)

senderSignature := parts[2]

if receiverSignature == senderSignature {

fmt.Println("The signature matches - the original message hasn't been modified")

part1Decoded := decode(parts[0])

part2Decoded := decode(parts[1])

fmt.Println(part1Decoded)

fmt.Println()

fmt.Println(part2Decoded)

} else {

fmt.Println("The signature differs - the original message has been modified")

}

}

func encode(text string) string {

return base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString([]byte(text))

}

func decode(text string) string {

decoded, _ := base64.RawURLEncoding.DecodeString(text)

return string(decoded)

}

func sign(part1 string, part2 string, secretPhrase string) string {

textToSign := part1 + "." + part2

signer := hmac.New(sha256.New, []byte(secretPhrase))

signer.Write([]byte(textToSign))

binarySignature := signer.Sum(nil)

return base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString(binarySignature)

}

A disclaimer: the author of this post doesn't know why they used a wish for Eric to go to the specific Norwegian village as their secret phrase.

I believe the code should be pretty straightforward, except maybe the sign function and the first part of the message:

{

"typ":"JWT",

"alg":"HS256"

}

Fear not, we'll discuss this soon. But I think now you should have a very good understanding of why Eric's prank didn't work once the signature was introduced - the if receiverSignature == senderSignature will return false in that case, so we won't even bother decoding the message.

I think it's a good moment to pause our interactions with the guys (we'll get back to them soon though), and try to map what we have learned so far to the main topic of this post - JWT.

JWT and JWS

If you have read the post all the way to this very point and began wondering why there is nothing about JWT/JWS/JWE yet, I have to say that it's a valid concern. But, hey, let me tell you this: with the things we have discussed above, you have learned almost everything I wanted to share about JWT and JWS. How come? Let me try to explain.

The (probably) most famous web resource about JWT - https://jwt.io - provides such a definition of JSON Web Tokens:

JSON Web Token (JWT) is an open standard (RFC 7519) that defines a compact and self-contained way for securely transmitting information between parties as a JSON object. This information can be verified and trusted because it is digitally signed. JWTs can be signed using a secret (with the HMAC algorithm) or a public/private key pair using RSA or ECDSA.

If we use a Wikipedia article about the JWT as a reference, we'll notice that it specifies the following structure of JWTs:

- header

- payload

- signature

Hmm...3 parts and our message had 3 parts - coincidence? Not really. Let's see what each part usually contains and compare it with the Craig and Clyde approach. A spoiler alert: we'll see soon enough that once guys took the anti-prank measures, they were using JWT/JWS format =)

Header

If you are familiar with the concept of HTTP headers, there is a similarity between the two in a way: the header part is used to pass some metadata. To be more specific: usually, the type of token and the algorithm used to generate the signature are provided there. Here is how it looks in our case:

{

"typ":"JWT",

"alg":"HS256"

}

It is clear to us that the type of the token is JWT, and the algorithm used is HS256, which stands for HMAC-SHA256. Algorithm info is very important for the receiver, as they need to know the way signature has been calculated, so they can follow the same algorithm in order to get the same result.

There is some variety of algorithms available for the signature in the JWT specification. They belong to 3 main groups:

- HMAC

- RSA

- ECDSA

The high-level key difference between them is the fact that the HMAC algorithms rely on the secret phrase (like we saw below), while RSA and ECDSA use a private-public keys pair for generating/verifying signature. We won't go deep into these algorithms, as it's way outside the scope of this post, but we'll discuss how to use private-public keys for JWT purposes further.

There are other header fields available in the JWT specification, but the two above are the most commonly used.

Payload

If we stick to the HTTP analogy, we can compare the payload with the request body, as this is the place where the domain-specific information can be found. The fields of the payload are called claims, and there is a list of the standard claims available in the JWT specification. To name a few:

-

iss- who issued the JWT -

sub- the user/application the token belongs to -

exp- expiration time for JWT -

nbf- not before, the time at which the JWT becomes valid -

iat- issued at -

jti- the unique identifier of the JWT

Users are free to include their own custom claims on top of these - we saw that in the Craig and Clyde example when they used the message claim for their needs:

{

"sub":"Clyde",

"iat":1710617091,

"message":"Hey, buddy! Board games tonight!"

}

Signature

Well, we have already discussed this part and even saw what the secret phrase flow looks like for it. Let me mention, though, that in the realm of JWT, the signature is called JSON Web Signature (or JWS) - so now you know 2 out of 3 acronyms mentioned in the title of this post - good job! =)

But let's another look at the code we wrote for the JWS:

func sign(part1 string, part2 string, secretPhrase string) string {

textToSign := part1 + "." + part2

signer := hmac.New(sha256.New, []byte(secretPhrase))

signer.Write([]byte(textToSign))

binarySignature := signer.Sum(nil)

return base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString(binarySignature)

}

Since we know now that for the signature we used the HMAC-SHA256 algorithm, the line

signer := hmac.New(sha256.New, []byte(secretPhrase))

should make good sense - all we do is initiate the signer that will follow the HMAC-SHA256 algorithm to generate the signature using the secret phrase we provided. The next steps are as simple as that:

- combine a header and a payload with the

.as a separator - please, note that both header and payload should be Base64URL encoded at that point - create a signature - it has a binary format

- apply Base64URL encoding to the binary signature to get it as a string

Well done! As we already know the receiver will follow the same steps and use the same secret phrase. That's the reason why the HMAC algorithm is known as a symmetric one.

For this example, we used HS256 as the algorithm, but quite often, you can see the HS384 or HS512 within the alg JWT header. As you might have guessed so far, it's still the HMAC algorithm, but with different hashing logic applied: SHA-384 and SHA-512, respectively.

HMAC, as any other symmetric algorithm, is a very decent one. However, there are certain cases when there is either no way to share the secret phrase between the parties in advance (remember that it was easy for Craig and Clyde, as they could meet in person before exchanging the JWTs) or the issues of JWT doesn't want to share it, as they want to be the only one who can issue that type of tokens. Imagine that the teacher of the class, Mr. Garisson, would like to send the scores for the math test in a JWT format. In that case, he wants to make sure that only he can issue that kind of token, as otherwise, some folks can try to hack the system and fake their scores. However, it is still important that there is a way for the receivers to verify the signature of the tokens. Here is when asymmetric algorithms like RSA and ECDSA come in handy.

Since this post is not about cryptography, we won't go deep into those algorithms but rather look at how we can use the asymmetric approach for the JWS needs. We'll stick to the RSA one, as I feel it's way more adopted in the industry these days, as it's an older one.

On a high level, the asymmetric algorithms rely on the concepts of the private and public keys. The private key is used for generating the signatures, and it is never shared with anyone by the JWT issues - remember Gandalf's rule of thumb "keep it secret, keep it safe". The public key, as the name suggests, is something that can be freely shared with anyone who needs to verify the signature - it can even be retrieved via the call to the specific public endpoint to simplify the flow. The main moment here is the following:

- private key can only generate the signature but not verify it

- public key can only verify the signature but not generate it

That's why such algorithms are called assymetric.

Here is how the signature flow looks for the sender - notice that it is very similar to the HMAC one:

- combine a header and a payload with the

.as a separator - please, note that both header and payload should be Base64URL encoded at that point - hash the resulted string by using the SHA-256 (for RS256) algorithm - it seems to be a new step, but only because the HS256 algorithm did it implicitly due to the Go implementation

- sign the hashed value by applying the RSA algorithm with the usage of the private key - the signature has a binary format

- apply Base64URL encoding to the binary signature to get it as a string

For the receiver the flow is a bit different:

- combine a header and a payload with the

.as a separator - hash the resulted string by using the SHA-256 (for RS256) algorithm

- verify the signature by applying the RSA verification algorithm with the usage of the private key and the signature attached to the JWT

Let's see how it looks in the code:

func main() {

// sender part:

fmt.Println("Sender part:")

privateKey, _ := rsa.GenerateKey(rand.Reader, 2048)

publicKey := &privateKey.PublicKey

header := `{

"typ":"JWT",

"alg":"RS256"

}`

payload := `{

"sub":"Clyde",

"iat":1710617191,

"message":"Hey, buddy! Board games tonight!"

}`

headerEncoded := encode(header)

payloadEncoded := encode(payload)

signature := sign(headerEncoded, payloadEncoded, privateKey)

encodedMessageWithSignature := headerEncoded + "." + payloadEncoded + "." + signature

fmt.Println(encodedMessageWithSignature)

// receiver part:

fmt.Println("\nReceiver part:")

parts := strings.Split(encodedMessageWithSignature, ".")

senderSignature := parts[2]

if verify(parts[0], parts[1], senderSignature, publicKey) {

fmt.Println("The signature is valid - the original message hasn't been modified")

headerDecoded := decode(parts[0])

payloadDecoded := decode(parts[1])

fmt.Println(headerDecoded)

fmt.Println()

fmt.Println(payloadDecoded)

} else {

fmt.Println("The signature differs - the original message has been modified")

}

}

func encode(text string) string {

return base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString([]byte(text))

}

func decode(text string) string {

decoded, _ := base64.RawURLEncoding.DecodeString(text)

return string(decoded)

}

func sign(header string, payload string, privateKey *rsa.PrivateKey) string {

textToSign := header + "." + payload

hashed := sha256.Sum256([]byte(textToSign))

binarySignature, _ := rsa.SignPKCS1v15(rand.Reader, privateKey, crypto.SHA256, hashed[:])

return base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString(binarySignature)

}

func verify(header string, payload string, signature string, publicKey *rsa.PublicKey) bool {

textToSign := header + "." + payload

hashed := sha256.Sum256([]byte(textToSign))

binarySignature, _ := base64.RawURLEncoding.DecodeString(signature)

err := rsa.VerifyPKCS1v15(publicKey, crypto.SHA256, hashed[:], binarySignature)

return err == nil

}

If we run the code, we'll see the following output:

Sender part:

ewogICJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLAogICJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIKfQ.ewogICJzdWIiOiJDbHlkZSIsCiAgImlhdCI6MTcxMDYxNzE5MSwKICAibWVzc2FnZSI6IkhleSwgYnVkZHkhIEJvYXJkIGdhbWVzIHRvbmlnaHQhIgp9.0F0WJ08wQOoXwuqJrvboAlEBOuSuSwFUxH-OZFnPOw7CUqXKVp9l8uYWPtizLuN3_RnrN5AwTIySCh5BQrh6c4TeTtVBgguonKDFYXvxA33DhUeB8Zzpa_1w_NXbS20Xg-ZysE6nOpZDkI9EhUajK9_p3ulJ7wmI_0DIOj1oX7OfjMHrwg7Kj4NrBLgjOPV9cFd6-FysUWJTRfW6OeF6rKK3jacO_Bhtw9dF8Igjt4ZFjHosRKjCth67agFex4SmN_qaRxTW0d0TZSL5c_bp_xWP-gwosNWPctJKzc-AEY51ZHc-7izpOrcQYwM5TGliVDyL1FvDVhXF6qhwtb8jWw

Receiver part:

The signature is valid - the original message hasn't been modified

{

"typ":"JWT",

"alg":"RS256"

}

{

"sub":"Clyde",

"iat":1710617191,

"message":"Hey, buddy! Board games tonight!"

}

Hopefully, this should make good sense now. You might have noticed that we are hardcoding the header and the payload part as strings, while the good practice here will be to rely on structs or, at least, a map. Good thinking, but I kept it like this to simplify the post and make it shorter - I believe I failed with the latter, though =)

One important undiscussed point remains: how does the receiver get the public key? The answer is: it depends. It is not wrong to share the public key somehow directly by sending a file or so. But that requires manual actions, and since humans are lazy, and laziness is a good driver of a progress, the industry came up with something smarter for that - JSON Web Key Set (JWKS).

JWKS

JWKS is a set of keys containing the public keys used to verify the JWT signature. JWKS is usually shared as a public endpoint. For example, Auth0 keeps them in https://{auth0CustomerDomain}/.well-known/jwks.json .

It looks something like this (the example is generated by ChatGPT):

{

"keys": [

{

"kty": "RSA",

"use": "sig",

"kid": "2",

"alg": "RS256",

"n": "vGtXtSE3pPmV...iC5X3kjMz4dVvw",

"e": "AQAB"

},

{

"kty": "RSA",

"use": "sig",

"kid": "1",

"alg": "RS256",

"n": "pVMOEtC2ZvYg...kPQ2E7pFCl5LZpM",

"e": "AQAB"

}

]

}

We'll skip some of these fields, as they are outside the scope of this post, but let's notice the kid which is a unique identifier for the key. This kid is added as a header to the JWT by the issuer, so the sender can find the corresponding public key by its ID within the JWKS.

This approach makes it very easy to rotate keys: once the new private key is issued, the corresponding public key is added to the JWKS with a new kid. Regardless of whether JWT was signed by the old or new private key, thanks to the kid, the sender can fetch the correct public key and successfully verify the signature. Simple as that!

Ok, we know now what JWT is, also we went through its structure and took a very good look at the signature part. But the key part is missing: why do we need JWTs at all? A good question!

Usage

While fellow developers out there might have come up with countless use cases for JWT, there are 2 most common scenarios for these tokens in the industry these days:

- authorization

- info exchange

Both of them can be perfect candidates for a separate blog, so I'll not only briefly elaborate on these scenarios.

Authorization

This is by far the most common use case for JWT. Usually, it looks like this:

- the user visits the website and presses the login button

- they enter their credentials (or use any other sign-in method)

- as a result, they receive the JWT, that, from now on, will be passed within the request to the server - as a rule of thumb, via the

Authorizationheader

In such a case, JWT can contain user identifiers and some info (like name, email, etc.) within its payload., as well as the list of permissions the user has.

Info exchange

As we have seen before, thanks to the signature mechanism, JWT provides a simple way of ensuring that the information hasn't been modified along the way, which makes it a good candidate for the information exchange format.

However, there is one critical moment to remember: JWT stores information in the open format, meaning that if intercepted, anyone can read it - as our example with the school dudes proved. But what if we'd like to pass something that should remain hidden from the unwanted guests? Shall we abandon the JWT format entirely in that case? These are excellent questions, and let's get back to the classroom to find the answers together with our old friends Craig, Clyde, and Eric.

Real-life example #2

There have been peace and balance for quite a while: Craig and Clyde kept exchanging messages in the JWT format with a signature, and Eric didn't manage to figure out how to bypass the signature protection but was partly satisfied by his possibility to be able to read every single message they sent. Until the day came when two friends needed to discuss something more privately: they had a very cool idea for a new video game, and the last thing they wanted was to share it with anyone else, especially Eric. Should they abandon their ways of messaging and start using mobile phones like the rest of their classmates? That sounded too simple and not nerdy at all, so "nope" was their answer. And they began thinking and asking themselves the right questions:

What is the key problem with the JWT in this case? The fact that the payload is passed in the opened format as the encoding (e.g., Base64) has nothing to do with the data protection.

Are there other ways, then? Of course, encryption! What stops us from encrypting the payload and passing it this way? Nothing. Let's do it then!

To achieve the desired result, the guys need to have one more secret phrase on top of the existing one and use it as the key for the encryption/decryption of the payload - they decided to use the symmetric algorithm again, as it is the most sufficient one for their use case. Once they have the key, they must add one extra step to their existing flow: encrypt the payload. Their signature should be calculated for the encrypted payload.

At first, Craig and Clyde wanted to encrypt headers as well, but then they realized that it was not the best idea, as otherwise, they wouldn't be able to tell each other about the algorithm they used for the encryption.

The same additional step applies to the message receiver flow: they need to decrypt the payload first and only then decode it. Here is how the sender and receiver flow looks on a code level:

func main() {

// sender part:

fmt.Println("Sender part:")

signingSecretPhase := "goToHellEric"

encryptionSecretPhase := "keepItSecretKeepItSafe"

jweHeader := `{

"typ":"JWE",

"alg":"dir",

"enc":"A256GCM",

}`

payload := `{

"sub":"Craig",

"iat":1710617455,

"message":"I think we should include elves in our videogame!"

}`

headersEncoded := encode(jweHeader)

payloadEncoded := encode(payload)

payloadEncrypted, _ := encrypt(payloadEncoded, encryptionSecretPhase)

signature := sign(headersEncoded, payloadEncrypted, signingSecretPhase)

encodedMessageWithSignature := headersEncoded + ".." + payloadEncrypted + "." + signature

fmt.Println(encodedMessageWithSignature)

// receiver part:

fmt.Println("\nReceiver part:")

parts := strings.Split(encodedMessageWithSignature, ".")

headersReceived := parts[0]

payloadReceived := parts[2] + "." + parts[3]

signatureReceived := parts[4]

receiverSignature := sign(headersReceived, payloadReceived, signingSecretPhase)

if receiverSignature == signatureReceived {

fmt.Println("The signature matches - the original message hasn't been modified")

headersDecoded := decode(headersReceived)

payloadDecrypted, _ := decrypt(payloadReceived, encryptionSecretPhase)

payloadDecoded := decode(payloadDecrypted)

fmt.Println(headersDecoded)

fmt.Println()

fmt.Println(payloadDecoded)

} else {

fmt.Println("The signature differs - the original message has been modified")

}

}

func encode(text string) string {

return base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString([]byte(text))

}

func decode(text string) string {

decoded, _ := base64.RawURLEncoding.DecodeString(text)

return string(decoded)

}

func encrypt(payload string, secretPhrase string) (string, error) {

hash := sha256.Sum256([]byte(secretPhrase))

secretKey := hash[:]

block, err := aes.NewCipher(secretKey)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

gcm, err := cipher.NewGCM(block)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

nonce := make([]byte, gcm.NonceSize())

if _, err = io.ReadFull(rand.Reader, nonce); err != nil {

return "", err

}

encodedNonce := base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString(nonce)

ciphertext := gcm.Seal(nil, nonce, []byte(payload), nil)

encodedCiphertext := base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString(ciphertext)

// The encrypted payload includes the IV and the ciphertext, separated by a dot.

return fmt.Sprintf("%s.%s", encodedNonce, encodedCiphertext), nil

}

func decrypt(encryptedPayload string, secretPhrase string) (string, error) {

hash := sha256.Sum256([]byte(secretPhrase))

secretKey := hash[:]

// The encryptedPayload includes the IV and the ciphertext, separated by a dot.

parts := strings.Split(encryptedPayload, ".")

if len(parts) != 2 {

return "", fmt.Errorf("invalid encrypted payload format")

}

encodedNonce, encodedCiphertext := parts[0], parts[1]

nonce, err := base64.RawURLEncoding.DecodeString(encodedNonce)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

ciphertext, err := base64.RawURLEncoding.DecodeString(encodedCiphertext)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

block, err := aes.NewCipher(secretKey)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

gcm, err := cipher.NewGCM(block)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

decrypted, err := gcm.Open(nil, nonce, ciphertext, nil)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

return string(decrypted), nil

}

func sign(part1 string, part2 string, secretPhrase string) string {

textToSign := part1 + "." + part2

signer := hmac.New(sha256.New, []byte(secretPhrase))

signer.Write([]byte(textToSign))

binarySignature := signer.Sum(nil)

return base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString(binarySignature)

}

I should warn you here: this code is written for educational purposes only, and while it was sufficient for the boys' case, it is not good enough for the proper production systems - please treat it like that.

If we run this code, we'll see that it works well. The resulting token looks like this:

ewogICJ0eXAiOiJKV0UiLAkKICAiYWxnIjoiZGlyIiwKICAiZW5jIjoiQTI1NkdDTSIsCQp9..4kt2psa8PhmBLfz6.G7zzu7eJRL0x8vomHI6f9mQF4XODm8TbWpo6f13AGlkczA3ceU5OtL1-gF9crSlYdsHIhfe_4Z0U2gwk_tWxf_GWW6MV1XDfDecPFSQJOJhcgLoeLRwdzvMN5SA73WsZdf6atY8tS1TfbZ-mcLLkyfcLdSsig1pBr33dQBRdbp1RQ9fqxyhpszQwRgCbDXBLcXUvFYFF0Y1_pgw.318c4zbUNCAU36s1uBn5H_LbHC_OB12gnd_oC3PRXwE

If you take a closer look, you'll see that its format differs from the JWT header.payload.signature one, as here we can see 4 dots instead of 2. What's going on? To answer this properly, we need to dive deeper into cryptography, and this post is not the right place for it. But let me give you a very short answer: to make sure that the receiver can decrypt the payload, the sender has to include additional parts to the token, so then the format looks like this:

header.encryptedKey.initializationVector.cipherText.cipherText

We know what a header is. The encryptedKey and the initializationVector parts are needed to decrypt the payload, as that's how some encryption/decryption algorithms work. The cipherText contains the encrypted payload, while the cipherText ensures the content hasn't been modified along the way. The code we wrote above mimics this, but with some hacks along the way, that's why I explicitly specified that it shouldn't be used outside this article.

But let's get back to our friends. As we saw above, the format of the message has changed. Eric also noticed it when the message came to him. "Hm, another trick, but I know what to do in such a case!" - he thought and began decoding each part of the message.

The ewogICJ0eXAiOiJKV0UiLAkKICAiYWxnIjoiZGlyIiwKICAiZW5jIjoiQTI1NkdDTSIsCQp9 converted into the

{

"typ":"JWE",

"alg":"dir",

"enc":"A256GCM",

}

"A good start!" - he thought. But then the situation got worse:

4kt2psa8PhmBLfz6 -> �Kv�Ƽ>�-��

G7zzu7eJRL0x8vomHI6f9mQF4XODm8TbWpo6f13AGlkczA3ceU5OtL1-gF9crSlYdsHIhfe_4Z0U2gwk_tWxf_GWW6MV1XDfDecPFSQJOJhcgLoeLRwdzvMN5SA73WsZdf6atY8tS1TfbZ-mcLLkyfcLdSsig1pBr33dQBRdbp1RQ9fqxyhpszQwRgCbDXBLcXUvFYFF0Y1_pgw

->

D1&dsZ:]Y

yNN~_\)Xvȅ$ձ[p

$ 8\-

;ku-KTmpu+"ZA}@]nQC(i40F�

pKqu/Eэ

318c4zbUNCAU36s1uBn5H_LbHC_OB12gnd_oC3PRXwE -> _64 ߫5/]s_

"Oh, no! Something is completely off, I can't see their messages!" - that was not his best day at school. And as he learned soon, there was nothing he could do about that - that's the beauty of the encryption.

I bet you have already guessed that we have been talking about a new concept all this time, and you might even have guessed what kind of concept it is - JWE or JSON Web Encryption.

JWE

Finally, we have reached the last term in this post's title, so if you are running out of tea or coffee, fear not - it is fine, as we are getting closer to the end of the post.

Since you have a very good understanding of JWT, it is easy to see why we sometimes need the encrypted version of it. As you have already noticed, the key difference between the two is that the payload is encrypted in the JWE, so only the designated actor can decrypt and read it.

Similar to JWS, JWE can use either symmetric or asymmetric algorithms for the encryption, and the logic is similar to the JWS:

- symmetric reuses the same key or pass pharse

- asymmetric uses a private key to decrypt the payload and a public key to decrypt it

There is a set of supported algorithms: to name a few, AES-CBC and AES-GCM are symmetric ones, and RSA-OAEP or ECDH-ES are asymmetric options. As with JWT, the algorithms are passed within the alg header. We won't try to reimplement the JWE asymmetric algorithms flow from scratch in this post, as it would be too artificial thing to do, considering the complexity of the cryptography behind it. However, later, I'll show you how to use proper libraries for that purpose - stay tuned!

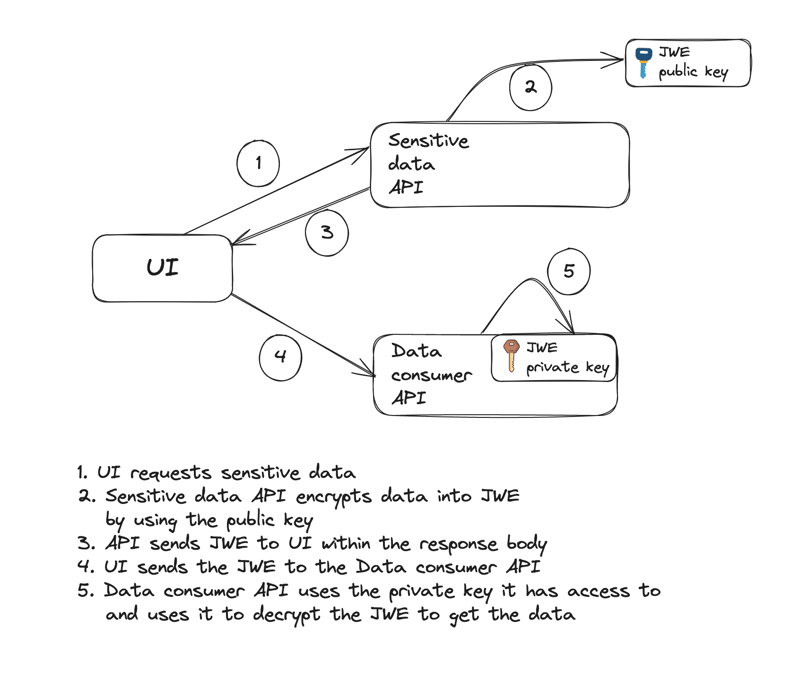

Remember we talked about the usage scenarios for JWT? The info exchange one is the primary use case for JWE, while it's not that common to use them for authorization (it still happens sometimes, though). Here is one of the possible ways of exchanging the data between the actors through the UI app with the use of the JWE:

Since it doesn't mean that step 4 will be invoked right away after step 3, the UI might need to store the sensitive data within the browser storage, which leaves the data easily accessible by the browser users and the UI app in general. That's why using the JWE can be a good solution here, as the Data consumer can decrypt the JWE and retrieve the data.

There might be one moment that I found confusing when I first came across it: the public key is used to encrypt the payload, and it can be publicly available, while the decryption is done by the private key that the receiver has access to. That's completely opposite from the signature algorithm - why is it so? Well, this is a very good question.

The answer, while confusing, uses logic as reasoning: if one of the keys should be public (so anyone can repeat the same operation), what is more sensitive in the scope of JWE: that anyone can encrypt or decrypt it? The answer is obvious: if anyone can decrypt it, that destroys the purpose of the JWE concept, that's why the decryption should be done with the private key, not the encryption.

There is one more important feature of JWE that I need to mention briefly: it is possible to nest a signed JWT inside the JWE, if there is a need to use the signature.

Nested JWS

As you might have noticed, the JWE structure has no signature:

header.encryptedKey.initializationVector.cipherText.authenticationTag

And while the authentication tag does its job to make sure that the data hasn't been modified by the man-in-the-middle (hey, Eric), there is one thing that signature does on top: verifies the senders' identity - the same way as the signatures we (humans) use to sing the documents. As discussed above, encryption can be performed with the public key if the asymmetric algorithm is used, so anyone can do that and pretend they are the issuer. When this part becomes a problem, both JWS and JWE must be combined by nesting it within. Here is how the structure will look:

JWE {

Header (encryption algorithm, content type, etc.)

Encrypted Key (if applicable)

Initialization Vector

Ciphertext (Encrypted {

JWS {

Header (signature algorithm, etc.)

Payload (data)

Signature

}

})

Authentication Tag

}

As you can see, JWS lives within the Ciphertext. In such cases, it is a good practice to pass the cty (content type) header with a value JWT to the JWE headers. This will hint to the receiver that the encrypted payload is not a set of claims, as usual, but rather a signed JWT.

All right, that's all I wanted to share about the JWE, as the remaining parts are the same/similar to the JWT concepts that we discussed quite thoroughly before. But before wrapping it up, The title of the article promised to show how to cook the JWT/JWS/JWE, so let's look at how it is done in real life. We'll be brief =)

How to cook them

I bet that even without me mentioning this, it was crystal clear to you that it's a bad practice to implement the JWT/JWS/JWE-related code from scratch. Good thinking! This is quite a trivial task to solve, and there are tonnes of battle-tested libraries in different programming languages for that matter, here is a quite comprehensive list provided by the Auth0. Anyway, it's always wise to check the library repo to see whether it's supported, what kind of issues are opened, when the last activity was and whether the license is sufficient for your needs. It is also smart to try it with the required scenarios before pulling the library into your project - but I bet you already know that.

Since I used Go for the examples above, let's use the Go JOSE library to show how it can help us.

JWT and JWS

Symmetric algorithm example

Here what the code looks for the symmetric HS256 algorithm:

import (

"crypto/sha256"

"fmt"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4/jwt"

"time"

)

type Payload struct {

jwt.Claims

Message string `json:"message"`

}

func main() {

// sender part:

fmt.Println("Sender part:")

signingSecretPhase := "goToHellEric"

// to make sure the secret is 256 bits long

// it's better to use 256 bits long string instead of doing this

hasher := sha256.New()

hasher.Write([]byte(signingSecretPhase))

signingSecret := hasher.Sum(nil)

payload := Payload{

Claims: jwt.Claims{

Subject: "Craig",

IssuedAt: jwt.NewNumericDate(time.Now()),

},

Message: "Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?",

}

var signerOpts = jose.SignerOptions{}

signerOpts.WithType("JWT")

singer, err := jose.NewSigner(jose.SigningKey{Algorithm: jose.HS256, Key: signingSecret}, &signerOpts)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

signedJwt, err := jwt.Signed(singer).Claims(payload).Serialize()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(signedJwt)

// receiver part:

fmt.Println("\nReceiver part:")

receiverJws, err := jose.ParseSigned(signedJwt, []jose.SignatureAlgorithm{jose.HS256})

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

verifiedPayload, err := receiverJws.Verify(signingSecret)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("The signature differs - the original message has been modified", err)

} else {

fmt.Println("The signature matches - the original message hasn't been modified")

fmt.Println(string(verifiedPayload))

}

}

If we run the code, we'll get this:

Sender part:

eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpYXQiOjE3MTE2MzEwNjIsIm1lc3NhZ2UiOiJIZWxsbyB0aGVyZSwgQ3JhaWchIFdoYXQncyB1cCwgYnVkZHk_Iiwic3ViIjoiQ3JhaWcifQ.tZ9j19pdM4vO7enkVSKuxoi6k3yB04aRlOKPzp_Rsnc

Receiver part:

The signature matches - the original message hasn't been modified

{"iat":1711631062,"message":"Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?","sub":"Craig"}

Asymmetric algorithm example

import (

"crypto/rand"

"crypto/rsa"

"fmt"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4/jwt"

"time"

)

type Payload struct {

jwt.Claims

Message string `json:"message"`

}

func main() {

// sender part:

fmt.Println("Sender part:")

privateKey, err := rsa.GenerateKey(rand.Reader, 2048)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

payload := Payload{

Claims: jwt.Claims{

Subject: "Craig",

IssuedAt: jwt.NewNumericDate(time.Now()),

},

Message: "Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?",

}

var signerOpts = jose.SignerOptions{}

signerOpts.WithType("JWT")

singer, err := jose.NewSigner(jose.SigningKey{Algorithm: jose.RS256, Key: privateKey}, &signerOpts)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

signedJwt, err := jwt.Signed(singer).Claims(payload).Serialize()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(signedJwt)

// receiver part:

fmt.Println("\nReceiver part:")

receiverJws, err := jose.ParseSigned(signedJwt, []jose.SignatureAlgorithm{jose.RS256})

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

verifiedPayload, err := receiverJws.Verify(&privateKey.PublicKey)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("The signature differs - the original message has been modified", err)

} else {

fmt.Println("The signature matches - the original message hasn't been modified")

fmt.Println(string(verifiedPayload))

}

}

The only difference here is that we need to generate and use RSA keys instead of a secret phrase. Usually, such keys are not generated by the application but rather stored somewhere, so the application reads them on its startup.

Here is the output of this code:

Sender part:

eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpYXQiOjE3MTE2MzEyODYsIm1lc3NhZ2UiOiJIZWxsbyB0aGVyZSwgQ3JhaWchIFdoYXQncyB1cCwgYnVkZHk_Iiwic3ViIjoiQ3JhaWcifQ.jZ4OIgCRyP2dHxa8wV_QqNYweT1p1ntGUfWHAxbHQyonAQAHhHcL75hCfPhxduGKqGU_dsrepKv6epBFGtMpUwlqvDiduQWKut0slqr6OQI_BedoQ8QB2Z9XdPM-smya7f1teEwYF9lDmU2Rz6s5pff_vwuuIQU2JRISg_fCKr0EqQv0Z5kvlxBeWJ3T5G0VBTTQccZZXkPCNovjT7eTXyChIQ8LT6RV4Fc5giLHi_-eydmJIcPCjJR2mjUk7-JI94b3QR2-ZTQcx96fbmMT3kp4RGn3r9SCAGAZQob43zxc2rcwEEEx07t4cuSa1BpJHrkzYA5bzpiRDH1fxWclyw

Receiver part:

The signature matches - the original message hasn't been modified

{"iat":1711631286,"message":"Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?","sub":"Craig"}

JWE

Symmetric algorithm example

import (

"crypto/sha256"

"fmt"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4/jwt"

"time"

)

type Payload struct {

jwt.Claims

Message string `json:"message"`

}

func main() {

// sender part:

fmt.Println("Sender part:")

encryptionSecretPhase := "goToHellEric"

// to make sure the secret is 256 bits long

hasher := sha256.New()

hasher.Write([]byte(encryptionSecretPhase))

encryptionSecret := hasher.Sum(nil)

payload := Payload{

Claims: jwt.Claims{

Subject: "Craig",

IssuedAt: jwt.NewNumericDate(time.Now()),

},

Message: "Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?",

}

encrypter, err := jose.NewEncrypter(jose.A256GCM, jose.Recipient{Algorithm: jose.A256GCMKW, Key: encryptionSecret}, nil)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

issuedJwe, err := jwt.Encrypted(encrypter).Claims(payload).Serialize()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(issuedJwe)

// receiver part:

fmt.Println("\nReceiver part:")

receiverJwe, err := jose.ParseEncrypted(issuedJwe, []jose.KeyAlgorithm{jose.A256GCMKW}, []jose.ContentEncryption{jose.A256GCM})

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

verifiedPayload, err := receiverJwe.Decrypt(encryptionSecret)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error decrypting the payload", err)

} else {

fmt.Println("The payload has been decrypted successfully")

fmt.Println(string(verifiedPayload))

}

}

The output:

Sender part:

eyJhbGciOiJBMjU2R0NNS1ciLCJlbmMiOiJBMjU2R0NNIiwiaXYiOiJhS2VNLWctT3BtYzBJeEhoIiwidGFnIjoiZk11aF9wemZ1UmlsNDgtOVJfRzIxZyJ9.1LAUhXXHcfcCHXftex9qVFhHTx3UnCK4R-Mc6jBsmtg.TagB8zrlcBTc2125.YHiktAQ0oPZ_Rdiptp3ok11v-Xbh4fts4ovgrcwqHFsMnVy-766R6Dg4utOGs8NoOW-C7SeQCSWRv5ojMo5ksnyPM-fKGmbXeRYZC32U2vsKxQ.IzBaULb22KI0vjA7NvuwZQ

Receiver part:

The payload has been decrypted successfully

{"iat":1711631810,"message":"Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?","sub":"Craig"}

Asymmetric algorithm example

import (

"crypto/rand"

"crypto/rsa"

"fmt"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4/jwt"

"time"

)

type Payload struct {

jwt.Claims

Message string `json:"message"`

}

func main() {

// sender part:

fmt.Println("Sender part:")

encryptionKey, err := rsa.GenerateKey(rand.Reader, 2048)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

payload := Payload{

Claims: jwt.Claims{

Subject: "Craig",

IssuedAt: jwt.NewNumericDate(time.Now()),

},

Message: "Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?",

}

encrypter, err := jose.NewEncrypter(jose.A256GCM, jose.Recipient{Algorithm: jose.RSA_OAEP, Key: &encryptionKey.PublicKey}, nil)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

issuedJwe, err := jwt.Encrypted(encrypter).Claims(payload).Serialize()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(issuedJwe)

// receiver part:

fmt.Println("\nReceiver part:")

receiverJwe, err := jose.ParseEncrypted(issuedJwe, []jose.KeyAlgorithm{jose.RSA_OAEP}, []jose.ContentEncryption{jose.A256GCM})

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

verifiedPayload, err := receiverJwe.Decrypt(encryptionKey)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error decrypting the payload", err)

} else {

fmt.Println("The payload has been decrypted successfully")

fmt.Println(string(verifiedPayload))

}

}

Output:

Sender part:

eyJhbGciOiJSU0EtT0FFUCIsImVuYyI6IkEyNTZHQ00ifQ.NNr1KAaT8gus0FEbvDWHBONo-CrXKy23aDQOZChKYm9mkuRHUX7NLj0G3ChuqCIy3jUDPsM_ICWQe4nX_XdJlBUnVN_-hKEPzaZ5cRcsNv_hKrohX657jRxcDxY15J9kVp68VaJsjG0rpPH69u1fDaT2kRNex5CZ54V-5Ywz0SvG0B_82pXDzoHfDxCCaKZFGQA7giBTJgaEsl1DVWB0xYHdZLo33JivSLGsKFUs48o_YSOKpbv5cnzSSj1cvrG5-36ousoPmJgIdkEqru8k_d6cG7T5xZILphYNrRaovBUT4IW2EZS4YpBoRxrZTLuXvN6ZcA-H78484PAqUZfxRA.qNhm_UONfkMr38Bv.BGciOa9CxI5iHou7TabTEhmXlJGr1OU-RPDvTx0FhzsPJUDUxF8cFRlDvIdNw7OdN_iblngtTSnB2hoEKpSfeHLQpqR1NwHfP2WufAnIexrjfQ.1uAbUYQR__j5Xtq4vW2t6g

Receiver part:

The payload has been decrypted successfully

{"iat":1711632447,"message":"Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?","sub":"Craig"}

Nested JWS

Asymmetric algorithms are used here for both signing and encrypting.

import (

"crypto/rand"

"crypto/rsa"

"fmt"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4"

"github.com/go-jose/go-jose/v4/jwt"

"time"

)

type Payload struct {

jwt.Claims

Message string `json:"message"`

}

func main() {

// sender part:

fmt.Println("Sender part:")

signaturePrivateKey, err := rsa.GenerateKey(rand.Reader, 2048)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

encryptionPrivateKey, err := rsa.GenerateKey(rand.Reader, 2048)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

signedJwt := issueJws(signaturePrivateKey)

encryptedJwe := encryptJwe(&encryptionPrivateKey.PublicKey, signedJwt)

fmt.Println(encryptedJwe)

// receiver part:

fmt.Println("\nReceiver part:")

decryptedJwe := decryptJwe(encryptionPrivateKey, encryptedJwe)

verifyJws(decryptedJwe, &signaturePrivateKey.PublicKey)

}

func issueJws(privateKey *rsa.PrivateKey) string {

payload := Payload{

Claims: jwt.Claims{

Subject: "Craig",

IssuedAt: jwt.NewNumericDate(time.Now()),

},

Message: "Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?",

}

var signerOpts = jose.SignerOptions{}

signerOpts.WithType("JWT")

singer, err := jose.NewSigner(jose.SigningKey{Algorithm: jose.RS256, Key: privateKey}, &signerOpts)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

signedJwt, err := jwt.Signed(singer).Claims(payload).Serialize()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return signedJwt

}

func encryptJwe(publicKey *rsa.PublicKey, signedJwt string) string {

encryptionOpts := (&jose.EncrypterOptions{}).WithContentType("JWT")

encrypter, err := jose.NewEncrypter(jose.A256GCM, jose.Recipient{Algorithm: jose.RSA_OAEP, Key: publicKey}, encryptionOpts)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

encryptedJwe, err := encrypter.Encrypt([]byte(signedJwt))

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

serialized, err := encryptedJwe.CompactSerialize()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return serialized

}

func decryptJwe(privateKey *rsa.PrivateKey, encryptedJwe string) string {

jwe, err := jose.ParseEncrypted(encryptedJwe, []jose.KeyAlgorithm{jose.RSA_OAEP}, []jose.ContentEncryption{jose.A256GCM})

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

decryptedJwe, err := jwe.Decrypt(privateKey)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return string(decryptedJwe)

}

func verifyJws(signedJwt string, publicKey *rsa.PublicKey) {

receiverJws, err := jose.ParseSigned(signedJwt, []jose.SignatureAlgorithm{jose.RS256})

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

verifiedPayload, err := receiverJws.Verify(publicKey)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("The signature differs - the original message has been modified", err)

} else {

fmt.Println("The signature matches - the original message hasn't been modified")

fmt.Println(string(verifiedPayload))

}

}

Output:

Sender part:

eyJhbGciOiJSU0EtT0FFUCIsImN0eSI6IkpXVCIsImVuYyI6IkEyNTZHQ00ifQ.DiGVfL5PqRL5phPdN-8rxNyeb1orfJTfseJzDzV4lcXurdTiCNJ0jnmNS2bG1yF7NfKSOC6yslasBmvpAQb2OCishTwAvWqIUj9BOByER73sYJKmtBhmLbHkzn19UEgo1ihA7s7LdrqtYCCepX3PVGAhGRsjIZp8BiSGpoc2TfEP4_MknEyEkoaukpqtXiBUUTRDfUNfzJg2gyC_ca1xu-jrwB2AbQyDw7cXQX4dsxpBstCmXnpThjlRrjMB7lE4Upc05aONakv_WLOLBjH1UInywPgihXQ9zpjsejPtWRfjJmwvV0AHKmvWYAZ-0YXg02LzYcmrOzPaQpTOgPC6PQ.dkRdR2yTUt3r3_OY.J8kh2oIqXF0YwDLCj06sPzkTLy9uwbsWE2M2DZYKmJLM5YCAHzuwYSDoXqkAM0cebEmks8zPtMOVMSKC-3wTXZOK3v13GyrcTfHIahDiuu2KwRqZOEB_7yJM0IgbCzLK_M8BWT_aTEtAqxDobUUU9TRsR0W7Zmn4pvO53jMQ3cRq2iIppSWkTR9W8DiW8xspCAxOhYMXymvQVGt4-bF1rThyrhvtXsKdMcIiWbO4MWV4mD9j1sVLVEXQDnLhNBT0wmGXYKRI-MsC0Ka1NupUs7ItcMqfcQnUL2GrjmH27dDtsuCCjkqo5xU-EISpLOx4z1kZna0iv8O9X_S30VtR-T4jAehwGx7aG3vUjBVSKOqkjVcA0YGez8FDehhk5Zlu0-yteMcad6nHjcn_qVRZL64ebTD053jIn4bLBz7YrgukcMp-NX7AwKbZ12AxoSXPWj75vZHie_oFevN3mEVFh6kFHg7I_6xzmXQA5QaLLPnFXtkSkf1x2KZldZ3PMK7NIrUuKYp1_rejqHJxtXL8HE3OnAAMfw_xdbSYDPT0WeEO7CxAZ5EWAfNJ1qZI3cRyDfFFKpeAIWL5u1BJS9Gte9QS1glsb7iZ_N_GZ6_Bjj4VvEfDMjwXidpxJvoQ-xLYNf2O9wKDVOTUaA.mbvor-v6UmO6u7ZGoHxY9Q

Receiver part:

The signature matches - the original message hasn't been modified

{"iat":1711638756,"message":"Hello there, Craig! What's up, buddy?","sub":"Craig"}

Things to be aware of

We spent a lot of time talking about JWT/JWS/JWE and also discussed how to implement them using the dedicated library. Everything sounds cool and logical, but are there any drawbacks to these concepts? Of course!

First of all, it is important to remember that JWS and JWE heavily rely on cryptographic algorithms, as we have seen so far, and that means that they are exposed to the same problems as any other things in that realm:

- cryptography is a complex subject, so it is easy to mess things up while implementing the algorithms. It's not rare that flaws are found in the JWT libraries; that's why it's important that the libraries we use are well-maintained and we have automatic ways of detecting and fixing security vulnerabilities in our projects with tools like GitHub Dependabot or similar ones.

- some cryptographic algorithms that have been used for a long time, can become obsolete and insecure, like, for example, MD5 these days. And JWT specification sometimes too slow to react on that, so it can still support those algorithms that should be avoided (for example, like this time in the past). It's our, engineers, responsibility to make sure that we are using reliable algorithms. Good linters can help detect this as well.

There is another crucial moment about JWT that many engineers have encountered if they had to work with the authorization domain: there is no way to revoke the JWT after it has been issued. As we discussed before, once the user provides their credentials, the JWT is issued to prove that the user is signed in. We can set up the expiry date for it, but imagine if the user clicked the "log out" button, JWT is still valid per se, but it shouldn't be trusted anymore in the scope of the user session. Some auth-providers handle this on your behalf, but others leave this problem to their users, so we, engineers, need to solve it somehow. One solution for this case is a DB table with the blocklist of revoked JWTs; we should keep them there until they expire.

There are other things to be aware of, but these are the most critical in my opinion.

Farewell

It's been a long journey, and it took me a few evenings to finish this post. So, thanks a lot for reading it, and I hope you have learned a thing or two about JWT/JWS/JWEs today. Before I say, "That's all, folks", let me share further readings if you'd like to dive deeper into the topics. And there is nothing more profound than dedicated RFCs:

- RFC 7519 - JSON Web Token (JWT)

- RFC 7515 - JSON Web Signature (JWS)

- RFC 7516 - JSON Web Encryption (JWE)

Have fun! =)

P.S. Receive an email once I publish a new post - subscribe here

P.P.S. I have created a Twitter account lately, so if you'd like to save my feed from ads, "funny" videos, and posts by Elon Musk, let's follow each other there =)

Posted on March 28, 2024

Join Our Newsletter. No Spam, Only the good stuff.

Sign up to receive the latest update from our blog.